Butterfield 1

Murder Rates and the Death Penalty: A Post-Moratorium Era

Brian Butterfield

University of Akron

Department of Economics

Senior Project

Spring 2020

Butterfield 2

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the entire Economics department for what I have learned during my

collegiate career. To specifically mention Dr. Renna, without whose dedication I would not have

made it through this senior research project. Additionally, Dr. Erickson’s constant feedback on

drafts helped keep me motivated. In an unprecedented time to be a graduating senior, her

telephone advice gave me the confidence to cross the finish line.

Thank you.

Butterfield 3

Abstract:

This paper intends to build upon the limited research in recent years that has

been conducted on the criminal significance of the death penalty. I pose to determine if

there is a significant deterrent effect of murder through the use of the death penalty in the

United States in a moratorium era. Given the controversy of the results of past studies, I

find that higher execution rates have a slight impact in raising the US murder rates. A 1

percent increase in execution rates increases murder rates by a slim 0.01 percent via

OLS. With using the panel data in a one-way fixed effects, the significance strengthens to

a 0.082 percent increase in murders for every 1 percent increase in executions.

Butterfield 4

Table of Contents

I. Introduction 5

II. Survey of Literature 8

III. Theoretical Model Development 11

IV. Model Specification and Results 14

V. Results Interpretation 17

VI. Conclusion 19

VII. References 22

VIII. Appendix 24

IX. SAS Code 27

Butterfield 5

I. Introduction

The Death Penalty Information Center reports that more than 165 individuals wrongly

accused of violent crimes have been executed in the United States since 1973. This does not

include others who had claimed their innocence. The death penalty is as controversial as gun

rights and abortion laws; even before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, there were

arguments for and against capital punishment in the colonies. As of 2020, the American divide is

greater than ever, with 30 states using the death penalty as legal recourse.

Much of the debate stems from the standpoint of morality. Supporters believe capital

punishment is a fitting penalty for the severity of the crime, and taxpayers should not be required

to support a murderer’s life sentence in prison. In contrast, opponents often object on the basis of

moral and religious principle. Some support the death penalty because they believe it prevents

crimes from being commmitted, while others disagree.

Butterfield 6

Figure 1: The comparison of murder rates between death penalty states and non-death penalty states (per 100,000 residents), per the

1

Death Penalty Information Center

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, (Figure 1) over the past 28 years,

states with the death penalty have a higher murder rate per 100,000 residents on average

compared to states that do not have capital punishment. The motivation for the research is not to

determine if there is a significant statistical connection nor a correlation between murder rates

and executions, although there is in fact a conflict in that research itself. The purpose is to

determine if there is a deterrent, and to what effect

. The economic motivation is twofold.

1

https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/murder-rates/murder-rate-of-death-penalty-states-compar

ed-to-non-death-penalty-states

Butterfield 7

It is important to note that from an economic perspective, the marginal benefits and

marginal costs are the most meaningful when studying allocative efficiency. The additional

benefits of the death penalty are those associated with life imprisonment. That is, the marginal

benefits are the difference between the total benefits of the death penalty and the total benefits of

life imprisonment. Many analyses produce monetary estimates of the cost to put one to death.

However, these studies produce total cost estimates, not marginal cost estimates. From an

economic perspective, society should only use capital punishment if the marginal benefits

outweigh the marginal costs. In the course of analyzing the economic efficiency of capital

punishment, and before providing any recommendations, both the benefits and costs of the death

penalty must be evaluated. Many innocent men die on death row, further creating rifts between

races and classes. The second economic motivation is to reduce murder in the United States,

where murder always negatively affects the economy and welfare of a society. Although this

study does not look at costs versus benefits of the death penalty specifically, it can lead to a

conversation about the viability of the punishment with more data given.

Capital punishment is again a highly debated topic in the United States because of the

moratorium of the death penalty. In a newfound era of controversy of the death penalty, with an

additional ten states at the turn of the century at least considered its moratorium, (Dezhbakhsh)

new evidence is needed on the effectivity of the punishment. Further study into the

post-moratorium states can help strengthen or weaken both sides of the arguments.

The Research Question

Butterfield 8

The aim of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of the death penalty as a murder

deterrent in a post-moratorium era in the United States, and whether it has changed from earlier

periods.

II. Survey of Literature

The fundamental basis of the link between crime and economics is derived from Gary

Becker’s economic theory of crime (1968). The theoretical framework applies simple economic

principles of consumer behavior in a market in which people choose to commit crimes. Becker

established that crime is committed on the basis of rationality, cost to benefit analysis of the

potential offender, and utility maximization. However, this analysis only pertains to rational

decision makers that commit a non-violent crime. Many studies used Becker’s theory to expand

on situations in which the perpetrator commits a violent crime, with assault, rape, and murders

being the forefront area of study. As a result, this original theory lead to the breakdown analysis

of murder versus capital punishment.

Building upon Becker’s original theory, numerous econometric studies have been

conducted to examine the effect of the death penalty as a murder deterrent. Most of the studies

use time series and panel data to measure the effect. Isaac Ehrlich’s (1975) research was one of

the original pioneering studies on whether execution rates cause a decrease in murder rates in the

United States. By extending Becker’s theory of the rational offender, Ehrlich developed a

positive approach towards testing the deterrence hypothesis using multiple regression techniques.

The study used U.S. aggregate time series data over a 35 year period as its structure, and

suggested a significant deterrent effect, sharply contrasting with earlier findings. Critics of

Butterfield 9

Ehrlich later addressed the issue of his findings: the proper functional form of the relationship

between the murder rate and its determinants. It is claimed that evidence of a deterrent effect is

found within the logarithmic form but not with the linear form, and therefore Ehrlich’s results

depended entirely on his choice of functional form.

Ehrlich inspired an interest in econometric analysis of deterrence, leading to many studies

that used his data, but included different regressors or different choices of endogenous vs.

exogenous variables. As a consequence, economists have argued against the viability of

researching the death penalty’s implication on homicide rates. Katz (2003) argued that the

quality of life in prison is likely to have a greater impact on criminal behavior than the death

penalty. Using state-level panel data covering the period 1950-1990, he demonstrated that the

death rate among prisoners (due to prison conditions) is negatively correlated with crime rates,

consistent with deterrence, and with robust findings. Furthermore, it was found that there is little

systematic evidence that the execution rate influenced crime rates in that time period.

Dezhbakhsh (2003) focused on post-moratorium panel data of the effect of the death

penalty as a murder deterrent. They examined the deterrent hypothesis using county-level,

post-moratorium panel data and a system of simultaneous equations. The procedure employed

overcame common aggregation problems using panel data from 1977-1996. It eliminated the

bias arising from unobserved heterogeneity, and provided evidence relevant for current

conditions, such as the current crime situation in the model. As a result, the findings suggested

that capital punishment has a strong deterrent effect, similiar to Ehrlich’s findings.

Introducing a panel study of United States state-level data over a twenty year period,

Zimmerman (2004) also estimated the deterrent effect of capital punishment. Specifically in this

Butterfield 10

paper, Zimmerman’s attention to detail addresses Ehrlich’s problem of endogeneity bias from the

non-random assignment of death penalty laws in each state and a relationship between murders

and the deterrence probabilities. The estimation results suggest that structural estimates of the

deterrent effect of capital punishment are likely to be downward biased due to the influence of

simultaneity. By correcting for simultaneity bias, the findings resulted in a stronger deterrent

effect. The results suggest that the announcement effect of capital punishment, (if potential

murders do actually witness an execution in proximity to the time in which they plan on

committing their offense) as opposed to the existence of a death penalty provision is the

mechanism actually driving the deterrent effect associated with state executions. Zimmerman

used the ordinary least squares method, along with fixed effects and two-stage least squares

regression analysis to come to this conclusion.

Finally, in a comprehensive survey of literature from 1973-2009, Nagin (2012) building

upon this earlier research, used panel data once more to determine whether the death penalty has

a deterrent effect on homicide, and if so, the size of this effect. The data includes all 50 states,

and the time periods covered are from the late 1970s through the late 1990s. Over this time

period, there have been variations in the frequency of death penalty sentences, executions, and

the legal availability of the death penalty. With these types of data, the strategy for identifying an

effect of the death penalty on homicides has been, roughly speaking, to compare the variation

over time in the average homicide rates among states that changed their death penalty sanctions

versus those that did not. No connection was established between these measures and the

perceived sanction risks, being caught, sentenced, and executed, of potential murderers. Neither

Butterfield 11

the fixed effects multiple regression models that were tested nor the proposed instruments in the

study were able to identify causation between capital punishment and murder rates.

This research will include updated annual data in the United States that has not been seen

in past literature. By studying a recent time period where additional states have imposed a

moratorium, the intent is to determine if the econometric findings are consistent with past

findings, or whether they yield different results. In addition, to differentiate from past literature

new variables will be added to test whether the effect of the execution rate is modified by these

factors. Like Dezhbakhsh and Zimmerman, for this research simultaneity must also be addressed

in order to yield more accurate results. I hypothesize the inclusion of new variables that account

for socio-demograpic differences will strengthen the murder deterrent theory from previous

authors.

III. Theoretical Development

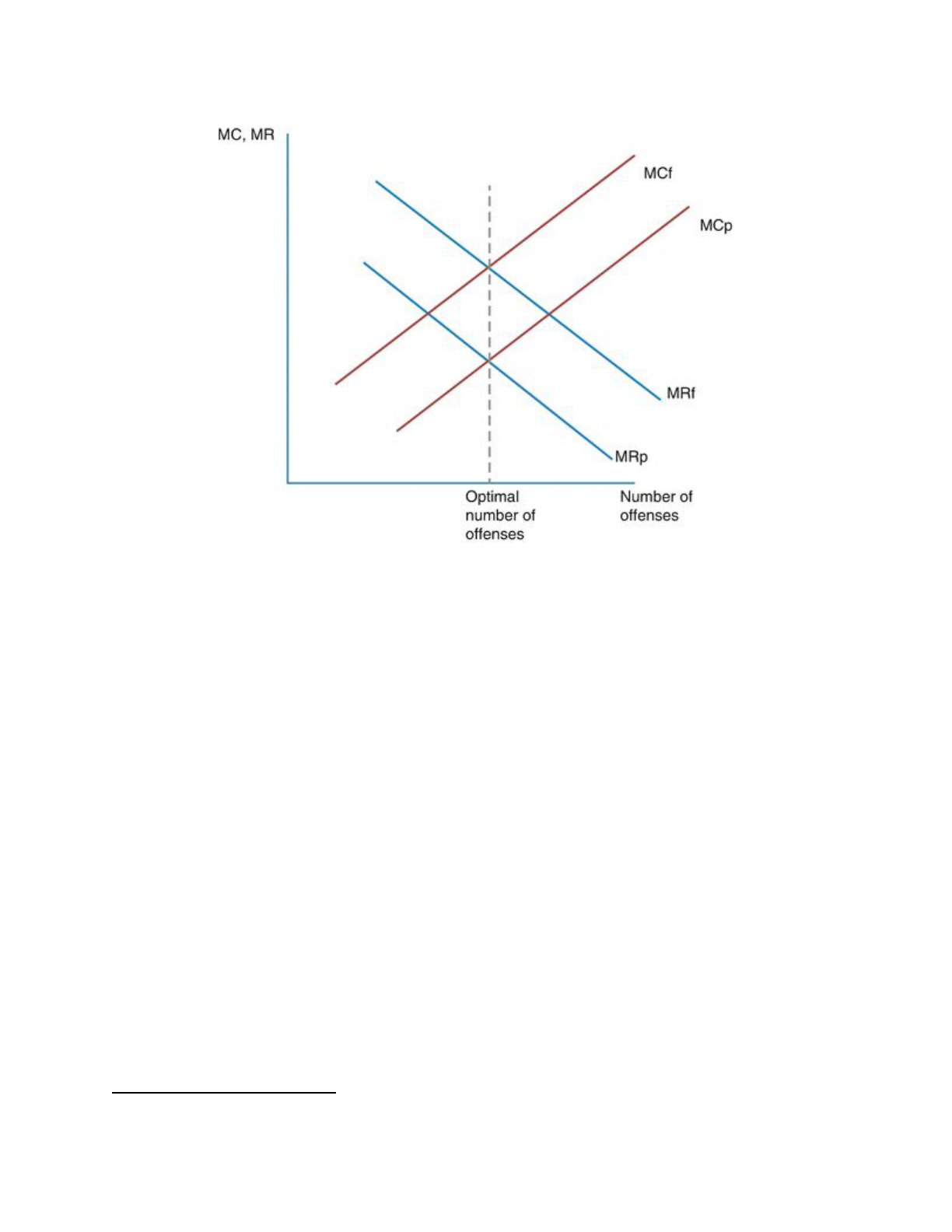

The basis of theoretical development is derived from Becker’s theory of crime (1968).

The theory, looking at an criminal’s likelihood to commit a crime as a rational individual that

makes their decision based on a “risk versus reward” approach is seen in figure 2:

Butterfield 12

Figure 2: Becker’s Theory of Crime

2

Becker explains with the increase of the total number of offenses, the marginal cost in

committing a crime increases, while the marginal revenue for the individual decreases. F

and P

represent the cost of punishment and the probability of conviction, respectively.

It has been noted that most individuals who commit murder do not adhere to rational

decision making; yet it can be expanded to most murders under the assumption that there is

always a risk-reward approach to a perpetrator’s actions. As a result, including all murders in a

population is not inappropriate. By expanding on Becker’s theory of crime, Daniel Nagin (2012)

furthered development research on the topic by creating the following model:

RDR f(Z ) X M

it

= α

i

+ β

it

+ γ

it

+ δ

it

+ ε

it

2

https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-1-4614-7883-6_17-1

Butterfield 13

The model shows that the murder rate ( ) is homicides per 100,000 residents inRDR M

it

state i

in year t

. is an expected cost function of committing a capital homicide that depends(Z )f

it

on the vector of death penalty or other sanction variables with the parameter measuring Z

it

γ

the effect of the death penalty on homicide rate. Importantly, this effect is assumed to be

homogenous across states i

and year t

.

This study applied certain economic and social modifications to examine how execution

rates affect the murder rates in the United States. Variables analyzed are first and foremost the

murder rates (per 100,000) in all fifty states, and total annual executions by year in all states.

Additionally, variables included were additional factors that could affect the outcomes, such as

unemployment rates. ( )X δ

it

I will use a panel data method similar to Nagin and Zimmerman. A primary benefit of

panel data is that one observes homicide and execution rates in the 50 states over multiple years.

This allows a researcher to effectively account for unobserved features of the state or of the time

period that might be associated with both the application of the death penalty and the homicide

rate. Some states may have different social norms or ways of thinking that could lead to a bias in

in murder rates or execution rates. The cultures in a progressive California and a more

conservative Texas are somewhat different in this regard.

The panel data accounts for these differences. , which is also referred to as the state α

i

fixed effect, allows the mean homicide rate to vary by state, while is the time fixed effect, β

it

allowing the mean homicide rate to vary over time. Finally, is the random variable that will ε

it

account for all error terms. This accounts for all the unobserved factors that determine the

homicide rate.

Butterfield 14

IV. Model Specification and Results

The empirical model used in this study is designed to examine the execution rate’s effect

on murder rates over the recent years in which some states have imposed a moratorium on the

death penalty. To properly examine the hypothesis, the state level panel data will cover the

periods of 2013-2017 for the 50 states, excluding the District of Columbia. This is to examine the

implications of the death penalty in a post-moratorium era in the country.

The econometric modeling used for the ordinary least squares and fixed effects models is

as follows:

nMU RDER lnExecution Incarcpcnt UnemRate Blackpcnt lnBachelor l

it

= β

0

+ β

1 it

+ β

2 it

+ β

3 it

+ β

4 it

+ β

5 it

+ ε

it

Where:

lnMURDER

is the dependent variable in the empirical model which measures the

murders per 100,000 residents by state by year.

lnExecution

measures all of the prisoners on death row who have been arrested,

convicted, and executed. This does not factor in any prisoners that were wrongly convicted, as

those who were executed innocently are a part of the execution statistics, and those who were let

go are not factored in. This coefficient is expected to have a negative sign since previous

findings either resulted in a negligible effect on the murder rate or a decrease in murder rate.

lnIncarc

measures the logarithm of the incarceration rate of a specific state. As

previously stated, being incarcerated is seen as a marginal cost that one associates with the risk

of committing a crime. If it is proof that incarceration is a deterrent in a rational offender’s

mindset when committing a murder, than a higher population in jail or prison may lead to an

Butterfield 15

offender’s thinking that there is a higher chance that they will not get away with their crimes,

resulting in the potential murderer not going through with the act due to the marginal cost of

them going to prison. This may be a matter of endogeneity however, and must be looked at

carefully. Consequently, the expected coefficient is expected to be negative according to

Becker’s theory of crime.

UnemRate

measures the unemployment rate percentage that comes from the number of

unemployed United States citizens divided by all that are currently in the labor force. According

to Grogger’s (1998) Model of Unemployment and Crime, as the unemployment rate goes up, the

crime rate, both violent and passive, is also expected to increase. This coefficient is expected to

have a positive effect on all of the occasions of murder.

Black

measures the percentage of African Americans in a state. This is an important

variable because it helps measure another aspect of state demographics. Past studies have found

that black males are affected by murder rates higher than white males and females. (Gender was

not included in this study because there are only a few rare exceptions when women have been

sentenced to death in the United States.) It is expected that black

is to have a positive effect on

murder rates, however the interpretation of this variable is complicated and must be taken with a

grain of salt. Zimmerman (2004) noted that race is one of the most controversial aspects of

capital punishment. In a review of numerous studies of the death penalty, the U.S. General

Accounting Office (1990) found that individuals who murdered whites were much more likely to

be sentenced to death than if their victim was non-white. I believe that this information will not

greatly affect the results of the ordinary least squares and fixed effect method, but it could affect

the interpretation of the results.

Butterfield 16

lnBachelor

measures the amount of the state population over 25 that has obtained a

bachelor’s degree. To include an education variable was critical because it measures certain

socio-demographics. Those with degrees have higher access to higher paying jobs which

theoretically incentivizes them to work in legal trades, and are generally more satisfied in their

adult lives. The variable is expected to have a negative impact, since more bachelor’s degrees

will likely result in higher quality of living, resulting in lower murder rates.

Murder rates consist of all three degrees of killing, including premeditated,

non-premeditated, (also known as a crime of passion) and manslaughter. It is important to note

that only premeditated murders are considered for the death penalty. The dependent variable in

the empirical model accounts for the total occurrences of all documented murders, with crime

data and statistics collected from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. It is important to note that these

murder rate statistics do not include all crimes that occur, but are reported and documented. This

aggregate data consists of the compilation of data collected by local law enforcement agencies

and federal law agencies.

To account for socio-demographic and state specific variables, the number of

unemployed citizens in a state, the percentage of the population over 25 with a bachelor degree,

and a proxy for race are added that accounts for a given state’s population of black citizens. All

of these variables are included in the panel data set and were sourced from the US Census

Bureau. The state specific economic variable of interest included in the study is the executions,

which was collected by the Death Penalty Information Center.

An incarceration variable was added as a deterrent variable, since it represents the

likelihood of an offender being caught and convicted. Increased incarceration rates would

Butterfield 17

theoretically have served as an increasing deterrent to commit a crime because it represents the

total marginal cost with committing a crime, rather than only the potential cost of getting caught

by an investigator or the police.

The panel data may not include all of the variables that may account for the variation in

the relationship between execution rates and murder rates since it is impossible to see all of the

variables that affect murder. This is an inherent flaw in ordinary least squares (OLS)

methodology that was originally conducted. To use all of the aspects of the panel data and

control for all of the different states and years, fixed effects were added to the state level data.

Fixed effects, a method used to assist in controlling for omitted variable bias due to unobserved

heterogeneity, are added to attempt to eliminate the variation in murders caused by factors that

vary across states but are still constant over time; also known as year-specific heterogeneity.

V. Results Interpretation

In order to determine if execution rates can affect murder rates both OLS and one-way

fixed effects models were used. In the econometric model, using an F-test to compare the

one-way fixed effect model to the OLS estimators showed that F=98.33 with p=0.0001. A

different and additional method of statistical analysis may have been able to identify a greater

estimation technique, but the results suggest that the model is improved when controlling for a

state fixed effect. I will now discuss the outcomes of the OLS estimation and controlling for the

fixed-effect.

Using OLS, I observed a 0.001 percent increase in murder rates for every 1 percent

increase in executions. However, this result was not statistically significant at a 90 percent level.

Butterfield 18

This finding changed when using the fixed effect method, strengthening to a 0.082 percent

increase in murders with the same increase in executions. The range set by standard deviations

was 0.057. At a 95 percent significance level, this is the most surprising aspect of the fixed effect

model as it relates to the variable of interest in the study. The fixed effect model found execution

rates to have a positive effect on the total rate of murders. This result is not in line with the

economic theory that an increased state execution rate results in a lower average murder rate.

There were also several other statistically significant variables in the first OLS model.

With 95 percent signifance, a one percent increase in unemployment resulted in a 0.04 percent

increase in murder rates in both the OLS and fixed effect models. Using the fixed effect model

compared to the OLS model saw no change in the significance level, with both at 95 percent.

The range set by standard deviation was 0.019. This coefficient is quite low, however, it is in line

with the theoretical framework suggesting that an increase in unemployment will increase the

amount of crime (Becker 1968).

The findings also suggest that for every one percent increase in a state’s incarceration

percentage, murders increased by 0.172 percent at a 95 percent significance level. Although once

again not in accordance with prediction and sentiment, the variable did not prove to be at a 90

percent significance level when tested with the fixed-effect method, which was to be expected

using that model.

Next, for every one percent increase in bachelor’s degrees, murder rates when tested with

the OLS method decreased by 0.088 percent. This proved to be in line with theory as murder

rates decrease with a higher education level. When testing using the fixed effects method, the

variable was found to be insignificant.

Butterfield 19

Finally, for every one percent increase in a state’s black population percentage, murders

increased by 0.031 percent. Originally tested at a 99 percent significance level with OLS, the

variable decreased in significance when tested at fixed-effect, decreasing to a 0.019 percent

increase in murders yet remaining at the 90 percent significance level. The range set by standard

deviation was 0.006. This result is in line with theory and sentiment, but as mentioned in the

variable discussion, it must be taken lightly. Black and white discrimination in the U.S. justice

system has been present for its entire history, and is likely a large determinant factor in guilty

murder convictions.

VI. Conclusion

In an effort to determine the capital punishment rate’s effect on murder rates in the

United States, the study concluded that there is not sufficient evidence that executions have some

impact on reducing murder rates, failing to satisfy my hypothesis. With improved methodology

compared to the OLS modeling, using fixed effects resulted in a 0.082 percent increase in

murders for every one percent increase in executions.

In a post-moratorium era for the death penalty, factoring in the findings, research would

suggest that prohibiting the use of capital punishment would decrease the number of murders. It

can be assumed that the use of capital punishment is near negligible, with figure 1 showing the

number of murders has decreased in the studied years compared to those previous.

In comparison to previous research, the study furthers the inconclusivity of the

homicide-punishment relationship. Dezhbakhsh (2003) found that there was a strong deterrent

effect, while Nagin (2012) and Katz (2003) found that there could be no established connection

Butterfield 20

between the two. When comparing the findings between post-moratorium years and previous

ones in the literature, the inconsistency in results continued.

There are some limitations in researching the effect of capital punishments on homicides

as a whole. The shortcomings in existing research suffer two specific flaws that make them

uninformative about the effect of capital punishment on homicide rates. First, the relevant

question regarding the deterrent effect of the death penalty is the “differential deterrent effect” of

execution compared to the detererrent effect of life imprisonment. Most convicts, regardless of

execution rates by state, are sentenced to life sentences without the possibility of parole and

never face death. None of the studies reviewed account for the severity of non-capital

punishment in their analyses. Second, the absence of the differential deterrent effect points out

the lack of study of how no capital punishment affects a potential murderer. With only the capital

punishment side being included in the studies, it presents a serious flaw of data interpretation in

the entire field of research.

For this study specifically, there were several limitations on my research. It is impossible

to capture all of the economic and intangible variables that could be a determinant of murders, so

there are likely to be several omitted variables that would benefit the model. Identifying these

variables would be beneficial in adding to the model’s explanatory power and a reduction to

omitted variable bias. Variables that could be included in future studies could account for more

socio-demographic issues, such as age groupings, income, and divorce rates. Furthermore,

locating data for more than the five years was troublesome, and more annual data would help

improve this study. Lastly, all of the aforementioned limitations in the field of study, such as

determining the proper homicide-capital punishment lag, made it difficult to analyze the research

Butterfield 21

with confidence even though many variables were statistically significant. If a different variable

could be used, a change in education would be appropriate. Using a high school diploma or an

associate degree variable would serve as a better education variable, since criminals tend to be

less educated (Lochner 2004).

It should be noted with past findings that even if executions are a deterrent to homicides,

it does not mean that capital punishment should be imposed. The sentencing of innocent inmates

to death is one of the many flaws of the United States justice system and its method of capital

punishment. Further measures must be enacted to ensure those uncommon mistakes do not

happen.

Butterfield 22

VII. References

Becker, G. S. 1968. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach

. Journal of Political

Economy 78, 526–536.

Dezhbakhsh, Hashem, Paul H. Rubin, and Joanna Shepherd. 2003. Does capital punishment have

a deterrent effect? New evidence from post-moratorium panel data

. American Law and

Economics Review 5:344–76.

Ehrlich, Isaac. 1975. The deterrent effect of capital punishment: A question of life and death

.

American Economic Review 65:395–417.

Grogger, Jeff. 1998. Market Wages and Youth Crime

. Journal of Labor Economics 16: 756–91.

Glaze, Lauren. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013.” Bureau of Justice Statistics

(BJS), 19 Dec. 2014, https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5177.

Kaeble, Danielle. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2014.” Bureau of Justice

Statistics (BJS), 29 Dec. 2015, https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5519.

Kaeble, Danielle. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015.” Bureau of Justice

Statistics (BJS), 26 Dec. 2016, https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5870.

Kaeble, Danielle. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016.” Bureau of Justice

Statistics (BJS), 26 Apr. 2018, www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6226.

Katz, Lawrence, Steven D. Levitt, and Ellen Shustorovich. 2003. Prison conditions, capital

punishment, and deterrence

. American Law and Economics Review 5:318–43.

Lochner, and Moretti. “The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates,

Arrests, and Self-Reports.” American Economic Review

, The American Economic

Association, 1 Mar. 2004, www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/000282804322970751.

Butterfield 23

Nagin, Daniel, et al. 2012. Deterence and the Death Penalty

. National Research Council of the

National Academies 4:48-71

U.S. General Accounting Office (1990), “Death Penalty Sentencing: Research Indicates Pattern

of Racial Disparities,” report GAO-GDD-90-57.

Zimmerman, P. R. 2004. State Executions, Deterrence, and the Incidence of Murder

. Journal of

Applied Economics, 7(1), 163–93.

“Population Distribution by Race/Ethnicity.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 4 Dec.

2019, www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-raceethnicity/.

Butterfield 24

VIII. Appendix

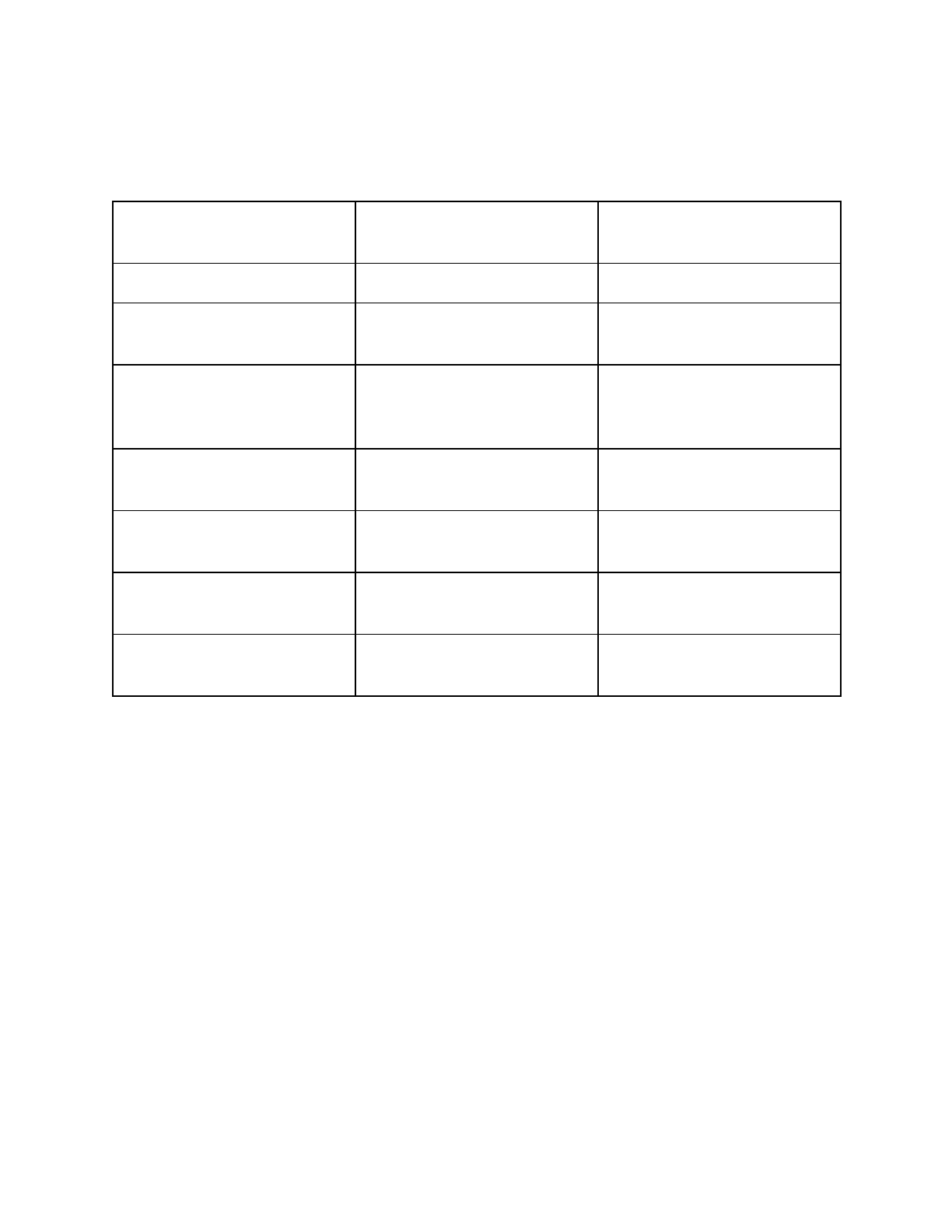

Table 1: Variable Definitions

and Sources

Variable

Definition

Source

lnMurder

Murders per 100,000

residents by state by year

Bureau of Justice Statistics

lnBachelor

Bachelor’s degrees per

100,000 residents held by

those 25 years and older

Bureau of Labor Statistics

lnExec

Total executions by year by

state

The Death Penalty

Information Center

UnemRate

Annual average

unemployment rate by state

Bureau of Labor Statistics

blackpcnt

percent of state population

that is black

US Census Bureau

incarcpcnt

percent of state population

that is incarcerated

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Butterfield 25

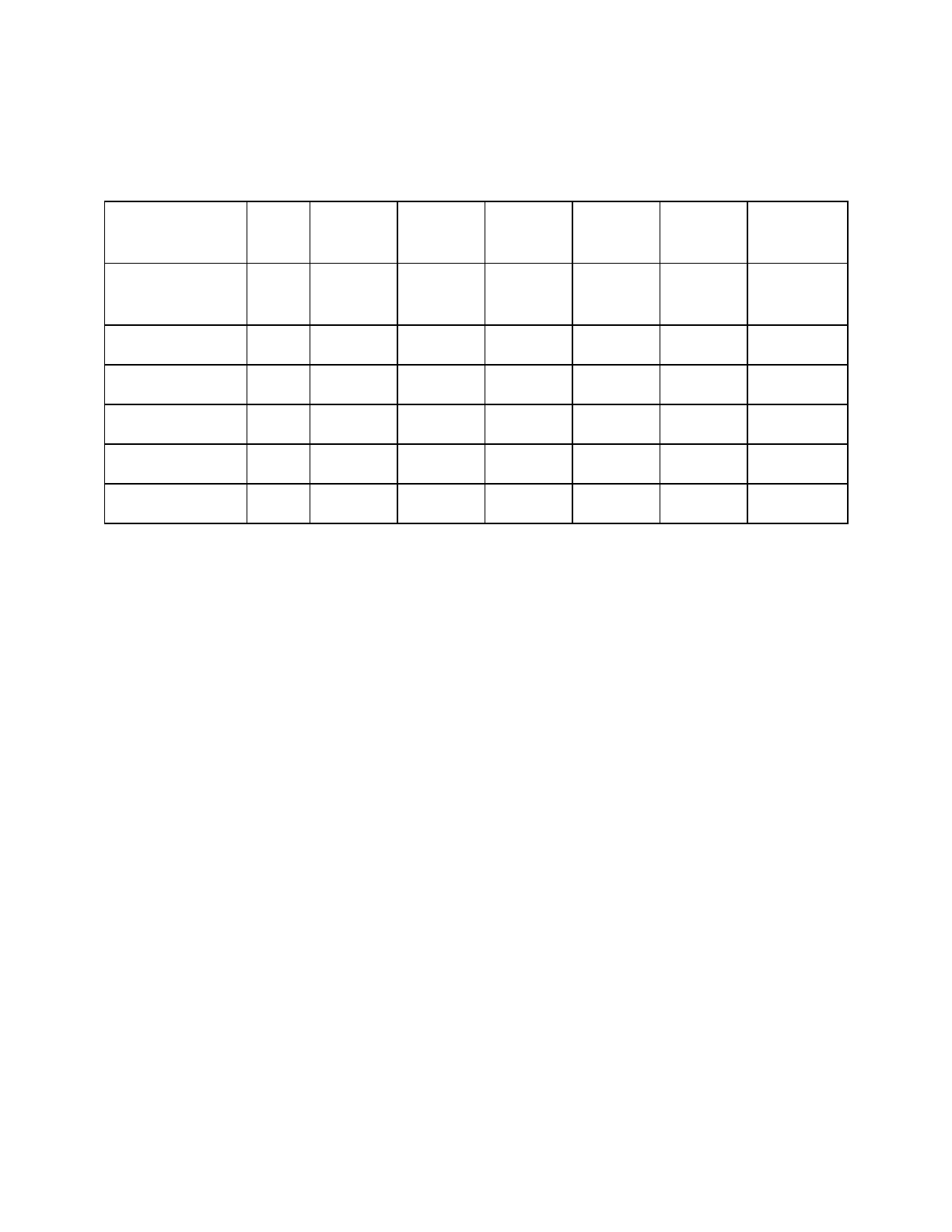

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics

Variable

N

Mean

Std Dev

Min

Max

Range

Expected

Sign

MurderRate

250

4.525

2.235

0.904

12.424

11.520

Dependent

Variable

UnemRate

250

5.252

1.471

2.400

9.600

7.200

+

BachelorRate

250

33.226

6.148

21.815

50.337

28.522

-

Exec

250

0.585

2.015

0

16.000

16.000

-

blackpcnt

250

9.800

9.112

0.374

36.447

36.073

+

Incarcpcnt

250

1.873

0.737

0.759

6.245

5.486

-

Note: 50 states shown in 5 observed murder years (2013-2017). All of the descriptive statistics

are shown before taking logarithms.

Butterfield 26

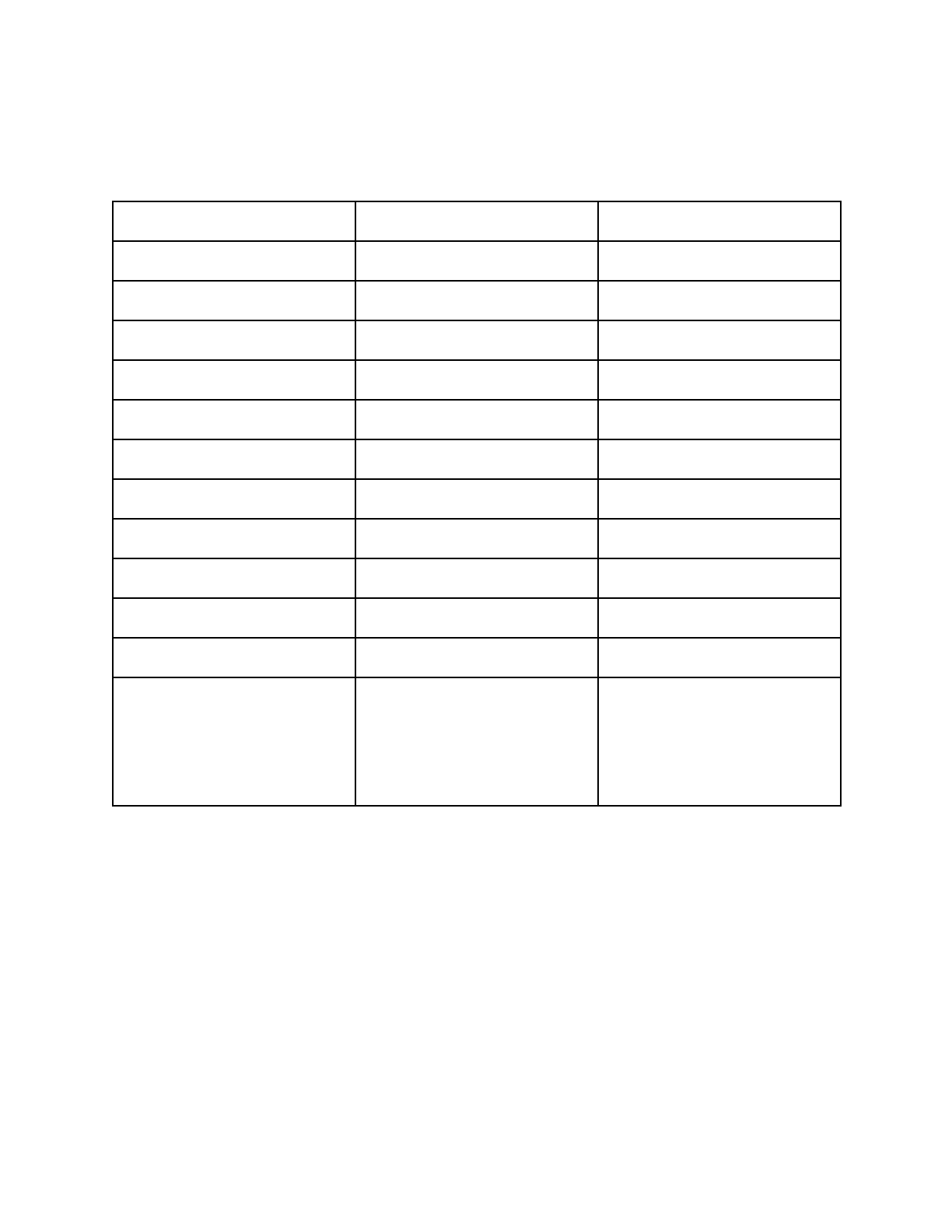

Table 3: Murders

Table 3: Murders/Execution

OLS

FE

Dependent Variable

lnMurder

lnMurder

Intercept

***0.7567*** (8.03)

-0.6931 (-0.32)

Unemployment

**0.040** (2.24)

**0.040** (2.09)

lnBachelor

***-0.088*** (-3.05)

-0.093 (-0.68)

lnExec

0.001 (0.10)

**0.082** (1.43)

blackpcnt

***0.031*** (10.16)

*0.019* (3.18)

incarcpcnt

**0.172** (2.31)

0.097 (1.66)

N

250

250

R-Squared

0.5248

0.8682

F-Value

53.89

97.33

Note: t-values are in

parenthesis. *,**, and ***

denote significance at the 90

percent, 95 percent, and 99

percent level, respectively

Butterfield 27

IX. SAS Code

/** Import an XLSX file. **/

PROC IMPORT DATAFILE="/folders/myfolders/SeniorProject/FINALEXCELDRFT2.xlsx"

OUT=WORK.sp2020

DBMS=XLSX

REPLACE;

RUN;

/** Print the results. **/

PROC PRINT DATA=WORK.sp2020; RUN;

proc means data=work.sp2020;

var Population Murder Black Unemployment Bachelor Exec Incarc;

run;

/** adtnlvar = aditional variables included**/

data adtnlvar;

set work.sp2020;

/** Murder Rate is murders per 100,000 state residents**/

/** Bachelor Rate is bachelor Degrees per 100,000 state residents**/

MurderRate = Murder/(Population/100000);

Butterfield 28

BachelorRate = Bachelor/(Population/100000);

lnIncar = log(Incarc);

blackpcnt = ((Black/Population)*100);

Incarcpcnt = ((Incarc/Population)*100);

lnBachelor = log(BachelorRate);

lnMurder = log(MurderRate);

lnincarce = log(Incarcpcnt);

proc means;

var Black Unemployment BachelorRate Exec

Incarc lnMurder lnIncar lnBachelor blackpcnt Incarcpcnt MurderRate;

run;

proc means;

var MurderRate Unemployment BachelorRate Exec blackpcnt Incarcpcnt;

proc reg data=adtnlvar;

model lnMurder = Unemployment lnBachelor Exec blackpcnt lnincarce;

run;

proc reg data=adtnlvar;

model lnMurder = Unemployment lnBachelor blackpcnt lnincarce;

proc sort data=adtnlvar;

by year;

proc panel data=adtnlvar;

title fixed effect murder rates;

Butterfield 29

id state year;

model lnMurder = Unemployment lnBachelor Exec blackpcnt

lnincarce/FIXONE;

run;