Making Peace Possible

NO. 157 | FEBRUARY 2020

PEACEWORKS

A Peace Regime for the

Korean Peninsula

By Frank Aum, Jacob Stokes, Patricia M. Kim, Atman M. Trivedi,

Rachel Vandenbrink, Jennifer Staats, and Joseph Y. Yun

NO. 157 | FEBRUARY 2020

Making Peace Possible

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of

the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website

(www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject.

© 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace

United States Institute of Peace

2301 Constitution Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20037

Phone: 202.457.1700

Fax: 202.429.6063

E-mail: usip_request[email protected]

Web: www.usip.org

Peaceworks No. 157. First published 2020.

ISBN: 978-1-60127-794-7

GLOBAL

POLICY

ABOUT THE REPORT

This report examines the issues and challenges related to establishing a peace

regime—a framework of declarations, agreements, norms, rules, processes, and institu

-

tions aimed at building and sustaining peace—on the Korean Peninsula. Supported by

the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace, the report also addresses how US

administrations can strategically and realistically approach these issues.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Frank Aum is senior expert on North Korea in the Asia Center at the US Institute of Peace.

Jacob Stokes, Patricia M. Kim, Rachel Vandenbrink, and Jennifer Staats are members

of its East and Southeast Asia program teams. Ambassador Joseph Y. Yun is a senior

adviser to the Asia Center. Atman M. Trivedi is a managing director at Hills & Company.

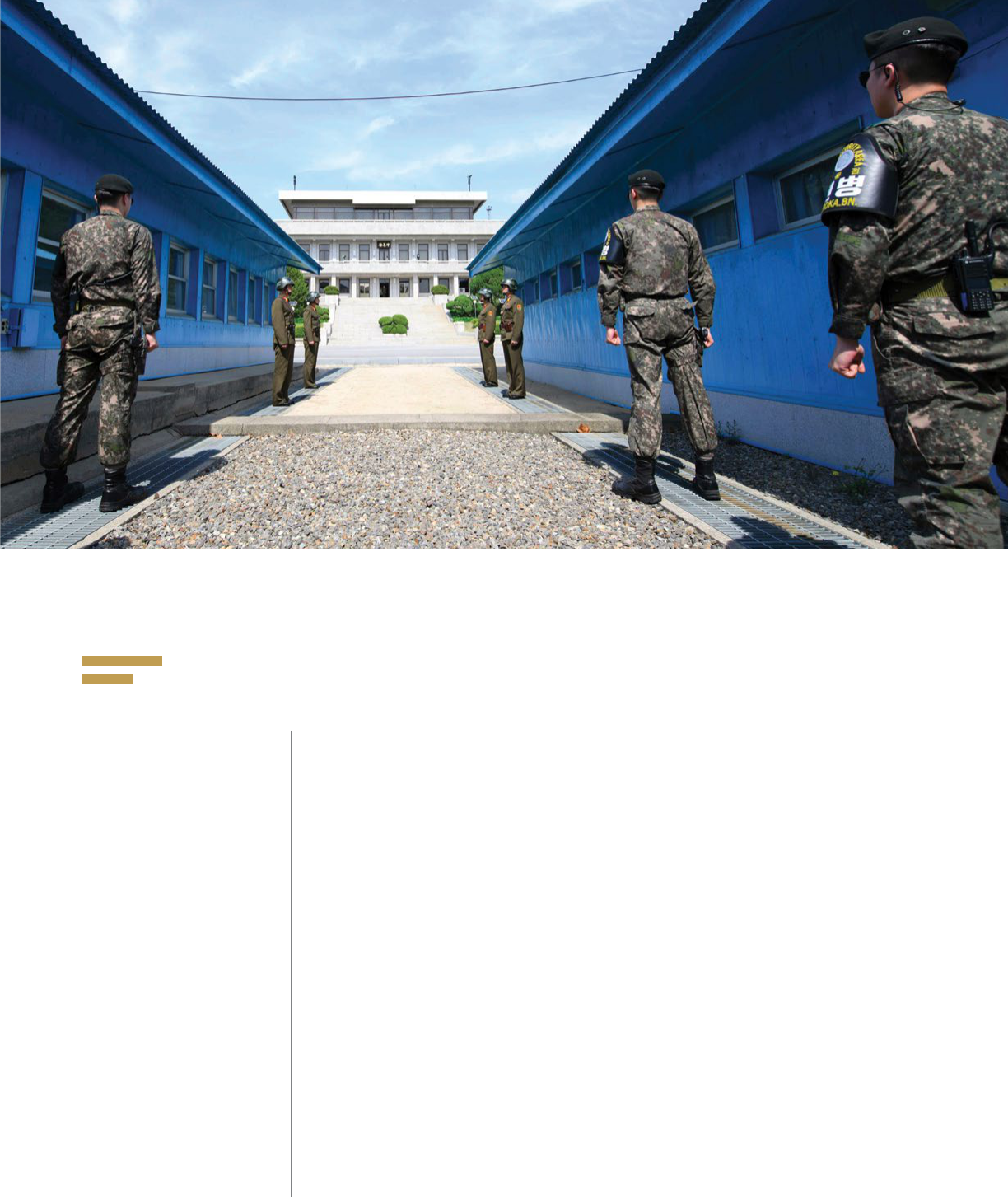

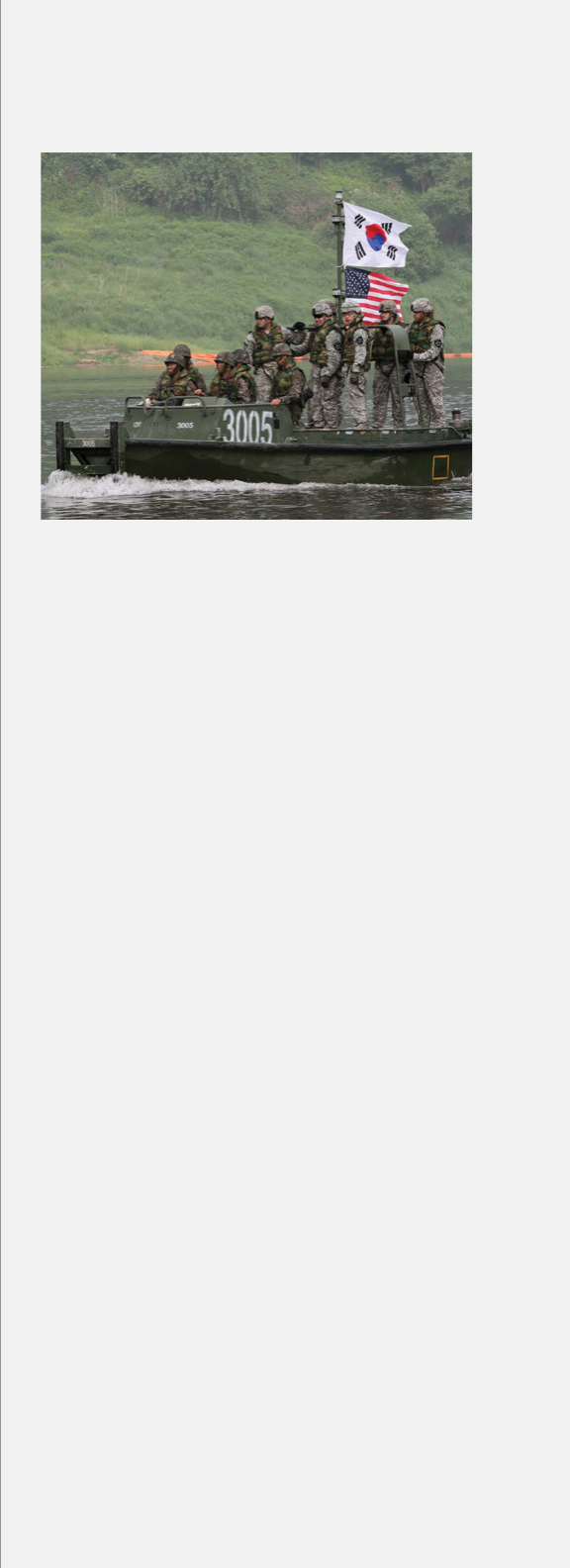

Cover photo: South Korean soldiers, front, and North Korean soldiers, rear, stand

guard on either side of the Military Demarcation Line of the Demilitarized Zone

dividing the two nations. (Photo by Korea Summit Press Pool via New York Times)

2

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

Summary

Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, few serious eorts have been made to

achieve a comprehensive peace on the Korean Peninsula. The unique aspects

of the diplomatic engagement between Washington and Pyongyang in 2018 and

2019, however, presented a situation that warranted both greater preparation for

a potential peace process and greater vigilance about the potential obstacles

and risks. Today, with the collapse of negotiations threatening to further strain

US-North Korea relations and increase tensions on the Korean Peninsula, a more

earnest and sober discussion about how to build mutual confidence, enhance

stability, and strengthen peace is all the more important.

Peace is a process, not an event. A peace regime thus represents a compre-

hensive framework of declarations, agreements, norms, rules, processes, and

institutions aimed at building and sustaining peace.

Six countries—North Korea, South Korea, the United States, China, Japan, and

Russia—have substantial interests in a peace regime for the Korean Peninsula.

Some of these interests are arguably compatible, including the desire for a sta-

ble and nuclear-free Peninsula. Others, such as North Korean human rights and

the status of US forces, seem intractable but may present potential for progress.

Understanding these interests can shed light on how to approach areas of con-

sensus and divergence during the peacebuilding process.

Certain diplomatic, security, and economic components are necessary for a

comprehensive peace on the Korean Peninsula. Denuclearization, sanctions relief,

and the US military presence have drawn the most attention, but a peace regime

would also need to address other matters—from procedural aspects such as which

countries participate and whether a treaty or an executive agreement should be

used, to sensitive topics such as human rights, economic assistance, and humani-

tarian aid, to far-reaching considerations such as the Northern Limit Line, conven-

tional force reductions, and the future of the United Nations Command. This report

addresses how US administrations can strategically and realistically approach the

challenges and opportunities these issues present, and then oers general princi-

ples for incorporating them into a peacebuilding process.

3

USIP.ORG

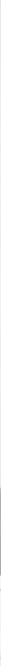

Since the signing of the 1953 Armistice Agreement established a military truce on the

Korean Peninsula, few serious endeavors have been undertaken to realize a “final

peaceful settlement” to the Korean War.

1

A variety of factors, including geopolitical

tensions, deep mistrust, poor mutual understanding, political expediency, and myopic

policymaking, have prevented diplomatic negotiations among the four major coun-

tries involved—the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea), the

Republic of Korea (ROK, or South Korea), the United States, and China—from advanc-

ing to the formal peacemaking stage.

To be sure, many limited eorts have been made to reach a peace settlement. The

first attempt, the 1954 Geneva Conference, reached potential agreement on the

issues of foreign troop withdrawal and the scope of elections for the Peninsula.

2

However, the conference ultimately foundered after two months over the question of

who would supervise these issues—the communist side favoring Korea-only or neutral

nations supervision and the US-led side supporting UN oversight.

Later, despite the grip of Cold War tensions on the Peninsula—China and the

Soviet Union backing the North and the United States supporting the South—the

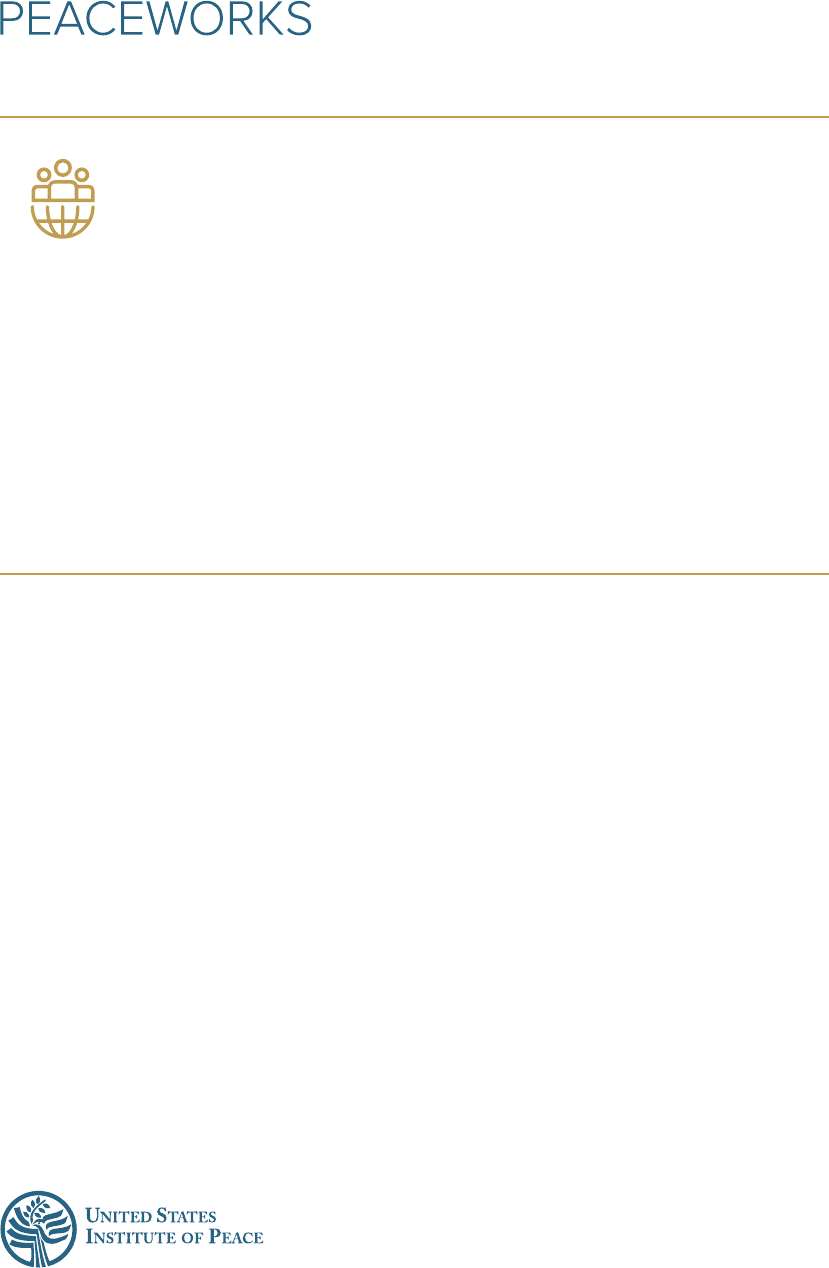

President Moon Jae-in of South Korea, right, and North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un, shake hands in the truce village of Panmunjom on April 27, 2018.

At center is the border between the two Koreas. (Photo by Korea Summit Press Pool via New York Times)

Achieving peace

on the Korean

Peninsula is possible

but it will be a

long and arduous

process. The first

step is elevating

peace as a priority.

Background

4

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

two Koreas took sporadic, incremental steps toward

peaceful coexistence and long-term reunification.

They achieved significant breakthroughs in diplomatic

relations and tension reduction, including the 1972

joint North-South Statement on reunification, the 1991

Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, and

Exchanges and Cooperation (Basic Agreement), and

the 1992 Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of

the Korean Peninsula.

These achievements, however, proved largely aspira-

tional because they could not resolve three fundamen-

tal issues. First, North Korea desired direct negotiations

and normalization with the United States, often sidelin-

ing South Korea in the process. Second, North Korea

continued to conduct violent acts against South Korea

(such as the 1983 assassination attempt of President

Chun Doo-hwan in Burma, the 1987 bombing of a

Korean Air flight, and the 2010 sinking of the ROK ship

Cheonan and shelling of Yeonpyeong Island), partly be-

cause of its own insecurity about the South’s growing

political and economic legitimacy. Third, it was unclear

how the two Koreas would accommodate mutually con-

tradictory conceptions of reunification following peace.

Advances in North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic mis-

sile program in the 1990s finally drew Washington into

negotiations with Pyongyang but further complicated

the prospects for peace discussions. Successive US

administrations prioritized denuclearization as the pri-

mary objective in negotiations and made it a precondi-

tion for discussing peace and diplomatic normalization.

After the 1994 Agreed Framework deal froze North

Korea’s nuclear facility at Yongbyon, US President Bill

Clinton and South Korean President Kim Young-sam

proposed Four-Party Talks with North Korea and China

in April 1996, the first major eort at peace negotiations

since the 1954 Geneva Conference. Unsure about US

intentions for the endgame, North Korea took more

than a year to respond.

3

When it finally engaged,

discussions about peace quickly collapsed because

of its insistence that US troop presence on the Korean

Peninsula be on the agenda.

4

A North Korea review

process led by former US Secretary of Defense William

Perry (but conducted separately from the Four-Party

Talks and ongoing US-DPRK missile talks) pushed the

two sides “tantalizingly close” to a deal that would have

banned North Korea’s production and testing of long-

range missiles in exchange for potential normalization

steps.

5

Because time was running out for his adminis-

tration, however, President Clinton chose to prioritize

promising Israeli-Palestinian talks rather than making a

trip to Pyongyang, believing that the next administra-

tion would consummate a deal with North Korea.

6

In the mid-2000s, the Six-Party Talks chaired by China

represented another attempt to address peace and

denuclearization under a “commitment for commitment,

action for action” approach.

7

Despite some confi-

dence-building measures, including North Korea’s shut-

ting down the five-megawatt reactor at its Yongbyon

facility, the United States’ removing North Korea from

its state sponsors of terrorism list and Trading with the

Enemy Act provisions, and the creation of working

groups focused on normalization, the talks again fell

apart in December 2008 when the two sides could not

agree on a formal protocol for verifying North Korea’s

nuclear activities. In the absence of a written protocol,

Washington, along with new, right-of-center govern-

ments in Seoul and Tokyo, insisted on suspending

energy assistance; Pyongyang responded by expelling

international inspectors.

8

The landmark June 2018 agreement reached in

Singapore between President Donald J. Trump and

Chairman Kim Jong Un—the first signed between the

Peace on the Korean Peninsula will require far more than a simple agreement, however.

A comprehensive regime consisting of declarations, agreements, norms, rules, processes,

and institutions will be necessary to build and sustain peace.

5

USIP.ORG

United States and North Korea at the leader level—

was the latest eort at forging a peace regime on

the Korean Peninsula. Under the agreement, the two

sides committed to “establish new US-DPRK relations”

and “build a lasting and stable peace regime on the

Korean Peninsula.” In addition, North Korea promised

to “work toward the complete denuclearization of the

Korean Peninsula.”

9

The inability of the two countries

to negotiate a more comprehensive agreement at a

second summit in Hanoi in February 2019, or since

then, underscores their entrenched positions and the

long-standing chasm that lies between.

Nevertheless, the Singapore agreement’s call for a

peace regime reinforced the need to examine this

issue in a thorough and timely manner. Also, the

unique aspects of this period of diplomacy—including

President Trump’s unconventional willingness to meet

with Kim Jong Un directly and to discuss peace and

denuclearization simultaneously, the severity of the

global pressure campaign against North Korea, the Kim

regime’s purported desire to shift from nuclear to eco-

nomic development, and the ostensibly cordial relation-

ship between the two leaders—presented a potentially

radical disjuncture from past negotiation scenarios.

10

Although the considerable obstacles were clear, the

moment warranted greater preparation for a poten-

tial peace. As this latest eort at diplomacy appears

to have failed and US-North Korea relations seem on

the brink of another downward turn, it is just as—if not

more—important to think through how to enhance sta-

bility, build mutual confidence, and strengthen peace

on the Peninsula without a formal peace agreement.

The limited number of ocial, multilateral eorts to

pursue a comprehensive peace regime has meant

equally few examinations of what it entails, how the

relevant countries view such an initiative, and what

issues and risks it involves. The focus of most parties

on the immediate challenges of North Korean denu-

clearization has further detracted from assessing the

long-term challenge of structuring peace on the Korean

Peninsula. The rapid development of North Korea’s

nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs and

the corresponding intensifying of the global sanctions

regime against North Korea significantly complicate a

potential peace process.

All parties interested in Korean Peninsula security

accept in principle the necessity of a peace regime to

ensure a permanent end to conflict. Peace will require

far more than a simple agreement, however. A compre-

hensive regime consisting of declarations, agreements,

norms, rules, processes, and institutions—spanning the

diplomatic, security, economic, and social spheres—will

be necessary to build and sustain peace. Furthermore,

the process will raise challenging questions about the

future of the US-ROK Alliance, the strategic orientation

of and relations between the two Koreas, the role of

the United States and China on the Korean Peninsula,

and the overall security architecture in the Northeast

Asian region.

Achieving peace on the Korean Peninsula is possible,

but it will be a long and arduous process. The first step

is elevating peace as a priority.

6

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

Perspectives

Six countries—North Korea, South Korea, the United

States, China, Japan, and Russia—have substantial in-

terests in how peace unfolds on the Korean Peninsula

and the implications for Northeast Asia. Many of these

interests are arguably compatible. For example, all

six parties support the goal of denuclearization of the

Peninsula, though following dierent definitions and

timelines; even North Korea has committed to this goal,

at least nominally, despite actions to the contrary. Some

disputes, such as the presence of US forces on the

Korean Peninsula or the human rights situation in North

Korea, seem nonnegotiable but may present areas

for progress after greater dialogue and trust building.

Other interests present challenges because they are

at direct odds (such as the sequencing of denuclear-

ization and reciprocal confidence-building measures)

or particular to just one country (such as Japanese

abductees). Understanding these interests can help

accentuate consensus areas while mitigating diver-

gences during the peacebuilding process.

NORTH KOREA

Since at least the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union,

North Korea’s approach to peace has been rooted

in its pursuit of regime security. To this end, the Kim

regime has focused on ending what it perceives as a

“hostile” US policy and transforming its overall rela-

tionship with the United States. The North has also

engaged with liberal South Korean governments to

reduce tensions and gain benefits, but it has long

perceived the United States as the paramount threat

to its security and the principal impediment to attaining

comprehensive, sustainable peace.

During periods of negotiations with the United States,

the regime has pursued this approach by securing US

commitments to move toward full normalization of polit-

ical and economic relations, provide formal assurances

against the threat or use of conventional and nuclear

weapons, ease economic and financial sanctions, and

respect North Korea’s sovereignty. The most recent

articulation of this goal was described in the June 2018

US-DPRK Joint Statement in Singapore, which com-

mitted the two countries to “establish new US-DPRK

relations” and “build a lasting and stable peace regime

on the Korean Peninsula.”

North Korea believes that denuclearization should be

the result, rather than the cause, of improved bilat-

eral relations between Pyongyang and Washington.

The regime insists, with China’s endorsement, that a

transformed relationship can only occur by both sides

taking “phased and synchronous measures” to build

trust slowly rather than Pyongyang being required to

denuclearize unilaterally and comprehensively up front

under a “Libya model” as suggested by then National

Security Advisor John Bolton.

11

For North Korea, measures for ending the “hostile” US

policy can be described under three categories: diplo-

matic, military, and economic.

For Pyongyang, an important demonstration of im-

proved US-DPRK ties is the normalization of relations.

North Korea believes that peace and security starts

with a mutual recognition of each country’s sovereignty

and parity, which can be accorded through normaliza-

tion. Normalized relations would also facilitate regime

legitimacy in other ways, including through enhanced

economic and trade relations, greater academic, scien-

tific, and technical exchanges, and improved standing

in the international community.

7

USIP.ORG

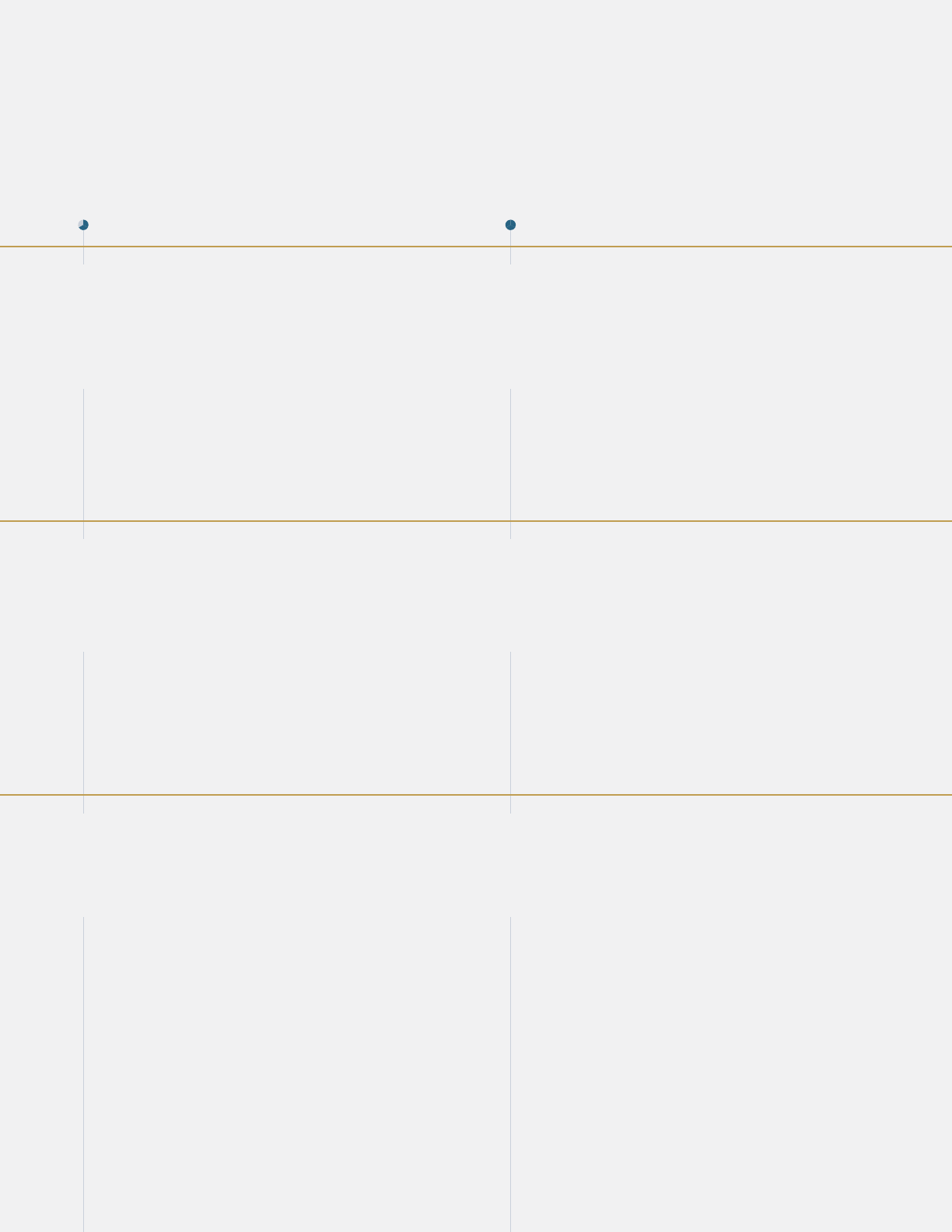

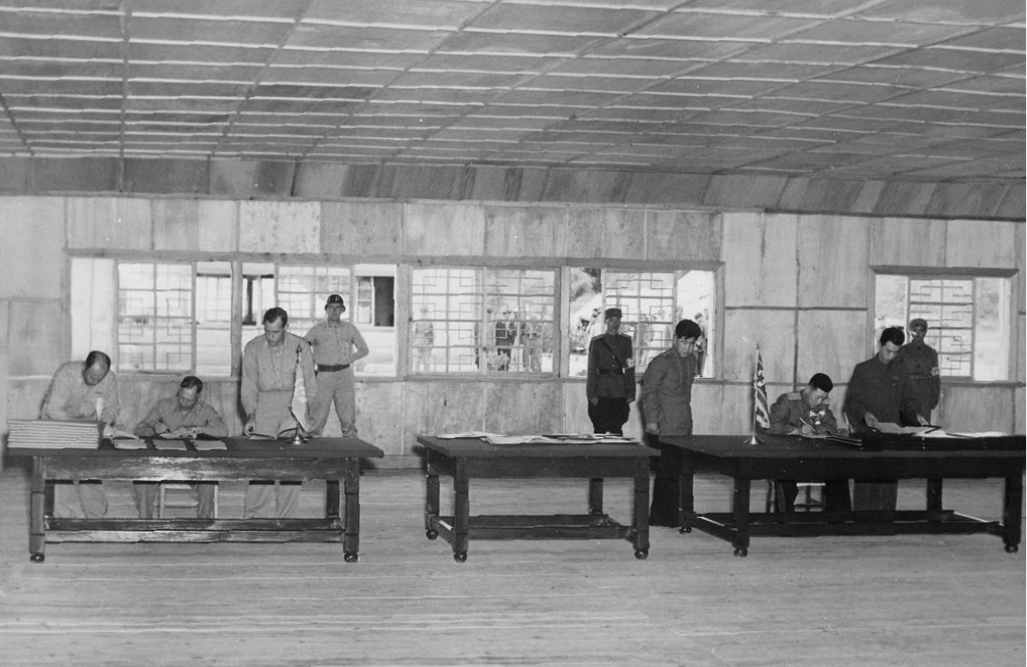

SOUTH

KOREA

NORTH

KOREA

CHINA

RUSSIA

JAPAN

Yellow Sea

(West Sea)

Sea of Japan

(East Sea)

Korea Bay

K

o

r

e

a

S

t

r

a

i

t

Seoul

Gwangju

Daejeon

Ulsan

Busan

Incheon

Daegu

Pyongyang

Wonsan

Yongbyon

Sinuiju

Hamhung

Chongjin

Tanchon

050

MILES

0 50 KILOMETERS

D

E

M

I

L

I

T

A

R

I

Z

E

D

Z

O

N

E

(

D

M

Z

)

Map 1. The Korean Peninsula

Artwork by Lucidity Information Design

8

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

North Korea views the US military presence in South

Korea and its joint exercises as a direct threat to

the regime’s security and a constant manifestation

of Washington’s hostility. To mitigate this threat, the

regime has sought military security guarantees from

the United States, which include not only assurances

against an attack but also an end to joint US-South

Korea military exercises and a reduction in—if not com-

plete withdrawal of—US forces on the Peninsula. The

regime has also made its own varying demands for the

denuclearization of the entire Peninsula, including the

removal of US nuclear and strategic assets from South

Korea and even in the region.

Despite its public emphasis on diplomatic normalization

and security guarantees, North Korea has consistently

demanded economic concessions in previous bilateral

and multilateral negotiations. Since 2018, it has focused

on gaining relief from the robust UN sanctions target-

ing the civilian economy that started with the adoption

of UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2270 in

March 2016. This eort also coincided with a shift in

the country’s strategy to prioritize economic develop-

ment rather than simultaneous development of nuclear

weapons and the economy (byungjin).

12

Experts disa-

gree on whether the move was a natural progression in

national priorities after the successful completion of its

nuclear force development, as North Korea claims, or a

response to the crippling eects of economic pressure,

as sanctions advocates argue.

North Korea has been equivocal and inconsistent about

how it prioritizes potential US and international conces-

sions. For example, at dierent points throughout the

1990s, North Korean ocials both expressed a willing-

ness to set aside the issue of US troops on the Peninsula

(such as during the 1994 Agreed Framework negotiations

and the 2000 inter-Korean summit) and demanded that

the issue be on the negotiating agenda (for example,

during the late-1990s four-party peace talks).

13

Former US

ocial Robert Gallucci, who negotiated the 1994 Agreed

Framework, noted that “from time to time there have

been indications that the North would like more political

freedom and less economic dependence on China and

is not so enthusiastic about an American departure from

the region.”

14

Similarly, North Korea has sometimes under-

scored its desire for sanctions relief, including making it

its highest priority during the February 2019 Hanoi sum-

mit negotiations, but in other instances has dismissed

its importance and instead emphasized the primacy of

security guarantees.

15

This equivocation may be an eort

to downplay the eect of sanctions and save face while

seeking economic relief. Ultimately, Pyongyang seeks

comprehensive security across the diplomatic, military,

and economic dimensions, but has demonstrated flexibil-

ity in its demands, depending on the circumstances and

potential corresponding concessions.

In the absence of diplomatic progress, North Korea has

sought to coerce the United States into ending its “hos

-

tile” policy by increasing its leverage through nuclear

and long-range missile testing, heightened tensions

on the Korean Peninsula, and improved relations with

China, Russia, and other countries. After the collapse of

negotiations in December 2019, Chairman Kim stated

that North Korea would revert back to “taking oensive

measures to reliably ensure the sovereignty and security

of our state.”

16

Many experts argue that even an end to

US enmity will not persuade North Korea to abandon

its nuclear weapons. Becoming a nuclear power has

been its highest security goal (if not national ambition) for

several decades. North Korean ocials have wondered

in various settings why their country was not treated like

India and Pakistan, which each possess nuclear weap-

ons and have normal diplomatic relations with other

countries but are not considered nuclear-weapon states

North Korea has sought to coerce the United States into ending its “hostile” policy through nuclear and

long-range missile testing, heightened tensions on the Korean Peninsula, and improved relations with

China, Russia, and other countries.

9

USIP.ORG

under the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

17

Given North Korea’s

claim that it has “finally realized the great historic cause

of completing the state nuclear force” with the successful

launch of its Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile

in November 2017, many US experts believe that North

Korea will likely continue to maintain its nuclear deterrent

because it is the best guarantee of regime security and

national sovereignty.

18

Accordingly, security guarantees

and promises of brighter economic futures will not be

enough to get significant traction on denuclearization be-

cause North Koreans view the US domestic political land-

scape as unpredictable and changes in administrations

triggering swings in Washington’s North Korea policy.

SOUTH KOREA

Given the proximate security risk from North Korea and

the fundamental yearning for reconciliation (and even

reunification), both liberal and conservative South Korean

administrations since the democratization period of the

late 1980s have generally pursued a policy of engage-

ment with the North. President Roh Tae-woo (1988–93),

inspired by West Germany’s Ostpolitik engagement

with Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union’s adoption of

glasnost, implemented a Nordpolitik policy in 1988 that

strengthened political and economic ties with communist

countries to help draw the North out of isolation. The

inter-Korean détente continued under President Kim

Young-sam (1993–98) and intensified under the sunshine

policies of Presidents Kim Dae-jung (1998–2003) and Roh

Moo-hyun (2003–8), leading to several breakthroughs,

including the Mount Kumgang tourism project in 1998, the

Kaesong joint industrial complex in 2004, and the first two

North-South summits in 2000 and 2007. Critics have ar-

gued, however, that the sunshine policy achieved tempo-

rary rapprochement at the expense of enabling and even

funding the North’s nuclear program and illicit behavior.

Subsequent conservative administrations adopted a

tougher, more reciprocal approach in engaging with

North Korea. President Lee Myung-bak (2008–13) con-

ditioned dialogue and humanitarian assistance on North

Korean steps toward denuclearization and openness;

President Park Geun-hye (2013–17) sought a middle

ground that emphasized mutual trust building as the foun

-

dation for peace and denuclearization. These engage-

ment eorts, however, were undermined by North Korean

provocations, which included four nuclear tests between

2009 and 2017, the sinking of the Cheonan and shell-

ing of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010, and a 2015 landmine

explosion in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Both adminis-

trations implemented a “proactive deterrence” policy that

aimed to thwart provocations by highlighting dispropor-

tionate retaliation, oensive capabilities, and preemption.

Pyongyang rejected this less accommodating approach

and viewed the conservative governments’ emphasis on

reunification as a hostile regime-change strategy.

The current Moon Jae-in administration reinvigorated the

sunshine policy of its liberal predecessors, highlighting

three main principles for a peaceful Korean Peninsula.

The first involves the renunciation of all military action

and armed conflict, whether it is a North Korean provoca-

tion or a US preventive strike. A military clash would not

only undermine peace eorts but could also potentially

lead to dangerous escalation. Second, President Moon

has emphasized the importance of denuclearization of

the Korean Peninsula. This point not only recognizes

that North Korea’s denuclearization is a prerequisite for

peace, but also rejects arguments by South Korea’s con-

servatives in support of indigenous nuclear weapons or

the redeployment of US tactical nuclear weapons.

The third principle stresses that the two Koreas must

play the primary roles in leading the peace process. This

principle stems from a strong desire for national self-

determination born out of decades of colonial occupa-

tion, foreign intervention, great power influence, and

North Korean refusals to engage with South Korea. In his

first meeting with President Trump in June 2017, President

Moon quickly secured US support for “the ROK’s leading

role in fostering an environment for peaceful unification

of the Korean Peninsula.”

19

A week later, in a speech

outlining his North Korea policy delivered in Berlin, he

declared that South Korea would be “in the driver’s seat”

10

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

of the Korean Peninsula. Nevertheless, South Korea

recognizes that the United States will play a leading role

on the basis of its authority over nuclear issues and the

North’s preoccupation with US enmity. Consistent with the

concept of self-determination, President Moon has also

adopted from previous sunshine policies the principle of

“no regime change” to allay Pyongyang’s fear that greater

engagement could lead to forced integration, absorption

by South Korea, or an end to the Kim regime.

With these three principles in mind, the Moon adminis-

tration has pushed for a step-by-step, comprehensive

approach to building and maintaining peace with North

Korea. The South’s invitation of a senior North Korean

delegation to the February 2018 Winter Olympics in

Pyeongchang began an inter-Korean thaw that led to

three North-South summits and a comprehensive military

agreement on tension reduction. Seoul also envisioned a

peace process beginning with an end-of-war declaration

by the end of 2018 and then subsequent steps toward

a peace treaty. Further, Seoul has pursued economic

cooperation and nonpolitical exchanges with the North,

promoting potential inter-Korean railway and energy

projects for mutual prosperity and seeking the reunion

of separate families to encourage reconciliation. At the

same time, the Moon administration has supported the

US-led “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign, includ

-

ing sustaining the unilateral May 2010 sanctions adopted

by previous conservative governments, and maintained a

policy of robust deterrence to urge the North to return to

talks and stay on the path toward peace.

Despite these successes, South Korea has run out of road

for advancing inter-Korean cooperation. Seoul will have a

dicult time moving forward on joint inter-Korean eco-

nomic ventures absent a US-DPRK agreement that allows

North Korea's Hwang Chung Gum and South Korea's Won Yun-jong carry the unification flag during the February 9 opening ceremony of the 2018

Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea. (Photo by Jae C. Hong/AP)

11

USIP.ORG

for at least partial relief from economic sanctions, includ-

ing those against joint ventures with North Korea. The

Moon government will also need to address North Korea’s

concern about Seoul’s ongoing military buildup, includ-

ing its acquisition of US F-35 stealth fighters. Moreover,

Pyongyang has grown weary of Seoul’s role as an “o-

cious” mediator, arguing that it should instead support the

interests of the Peninsula.

20

For his part, President Moon

recognizes the limitations of his five-year, single-term

presidency and has begun eorts to institutionalize the

Panmunjom Declaration reached during the April 2018 in-

ter-Korean summit by ratifying it in the National Assembly

so that it is binding on future administrations.

21

UNITED STATES

The US perspective on a Korean peace regime is driven

by its broader national security interests, primarily the

elimination of North Korea’s weapons of mass destruc-

tion and the need to maintain US strategic presence and

influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Washington maintains

a laser focus on ending North Korea’s nuclear program

and considers denuclearization the linchpin of any

improvements to the security situation on the Peninsula.

Indeed, for many US analysts, a peace regime would

flow naturally from ending Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons

program—and remain out of reach without it.

A minority of US analysts have broached the potential

for a peace regime under an arms control model that

reframes denuclearization as an ambiguous or long-

term goal and focuses on managing the growth of North

Korea’s nuclear program in the short term.

22

Believing

that North Korea will not denuclearize anytime soon, they

advocate taking more realistic steps focused on capping

Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal, locking in a nuclear and mis-

sile testing freeze, cultivating crisis stability and controlling

military escalation, and advancing a political framework

for peace based on deterrence and arms control. That

view, however, currently stands outside the mainstream

of ocial thinking because it could require a tacit accept-

ance of North Korea as a nuclear power if an arms control

agreement were construed as the endpoint rather than

starting point for a process aimed at full denuclearization.

Relatedly, many Washington analysts worry about permit

-

ting conditions that could induce South Korea and Japan

to acquire their own nuclear weapons. Some believe that

North Korea could conceivably threaten to use its nuclear

weapons to deter the United States from intervening to

stop North Korean aggression against the South.

A potential peace regime raises dicult security ques-

tions for Washington about the US-ROK Alliance,

American military presence in South Korea, and US strate-

gic posture in Northeast Asia. Any moves within a peace

process that undermine the pillars of the existing US-led

regional security architecture would encounter significant

opposition. The United States would in theory welcome

a peace regime whose principal eects were the consol-

idation of North Korean steps to end its nuclear program

and curtail its human rights abuses, and a reduction of the

potential for war between North and South. Washington

would also be amenable to a peace regime nested within

a wider, US-backed regional political and security order.

Therefore, a central question for the United States in

evaluating a potential peace regime is whether it would

require Washington to accept a reduction to its desired

force posture and level of influence in the region. North

Korea, China, and Russia would welcome an outcome

that diminishes US influence, but the United States wants

to avoid weakening its strategic position in Asia—espe-

cially if the promises of a peace regime prove illusory.

Given these considerations, Washington has historical-

ly favored incremental over sweeping changes on the

Korean Peninsula, thereby upholding the status quo. US

policymakers tend to dismiss North Korean, Chinese, and

Russian arguments about US regional military posture

being excessively threatening toward Pyongyang. From

Washington’s perspective, the only credible threat to

peace and security on the Peninsula is the Kim regime.

Therefore, although the United States wants North Korea

to move as rapidly as possible to dismantle its nuclear and

missile arsenals, it prefers to move slowly and methodical-

ly on the other components of a peace regime.

12

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

THE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN

PEACE, DIVISION, AND REUNIFICATION

The relationships between Korean

peace, division, and reunification

have been in tension since 1945.

Both Koreas were unhappy with the

division and actively sought to reunify

the Peninsula by force. Kim Il Sung at-

tacked South Korea in 1950 with the

aim of reunification. Three years later,

South Korean President Syngman

Rhee refused to sign the armistice

because he wanted the war to con-

tinue until reunification was achieved.

The notion of peaceful coexistence

was unthinkable to both leaders.

a

By the early 1970s, as Washington

signaled a desire to reduce tensions

with China and the Soviet Union and

to decrease its defense burden in

the region, the two Koreas took steps

toward rapprochement. North Korea

viewed North-South dialogue as a

way to decouple Seoul from Wash-

ington and Tokyo and hasten the

withdrawal of US troops; South Korea

saw engagement with the North as a

hedge against US abandonment.

b

In

1972, the two countries signed a joint

statement to promote the unification

of the Peninsula through nonviolent

means and independent Korean

eorts. Later, the 1991 Basic Agree-

ment signaled an implicit understand-

ing that peaceful coexistence was a

precursor to reunification.

Since 2000, the two Koreas have

recognized that their respective

approaches to reunification have ele-

ments in common.

c

The North Korean

proposal for a Democratic Confederal

Republic of Koryo envisions reunifi-

cation under a one-state, two-system

approach in which the two govern-

ments maintain autonomy in manag-

ing diplomatic, military, and economic

aairs. This system would be a transi-

tional phase for the ultimate end state

of a single-system country. Similarly,

South Korea’s National Community

Unification Formula uses a three-

stage approach that would begin with

a period of reconciliation and cooper-

ation, followed by the formation of an

economic and social commonwealth

(like the European Union), and then

the final realization of a unified state.

d

These positions are not static, how-

ever, and have evolved with changes

in the security environment and each

country’s security interests.

Fundamental dierences in the two

plans will make a unified state di-

cult to operationalize. South Korea’s

constitution calls for a unified Korea

based on a “free and basic demo-

cratic order.” North Korea’s approach

seeks to preserve its socialist system

and requires the removal of US forc-

es, which it believes contributed to

the division in the first place.

Analysts generally view the prospect

of a democratic South Korea and

an authoritarian North Korea living

in peace as a waypoint to eventual

unification. Nevertheless, whether a

peace regime would extend or short-

en the timeline for unification is not

agreed. The Moon administration and

other engagement advocates believe

that a peace process, by encourag-

ing cooperation and the exchange of

ideas, goods, and people, can build

mutual trust and facilitate the path

to not only denuclearization but also

Notes

a. “The idea that Korea could be separated into Northern and Southern parts and that the parts should coexist is very dangerous,” Kim said in

November 1954. “It is a view obstructing our eorts for unification” (Chong-Sik Lee, “Korean Partition and Unification,” Journal of International

Aairs 18, no. 2 (1964): 230–31).

b. Don Oberdorfer, The Two Koreas : A Contemporary History, rev. ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 25–26.

c. Dae-jung Kim, “North and South Korea Find Common Ground,” New York Times, November 28, 2000, www.nytimes.com/2000/11/28/opinion

/IHT-north-and-south-korea-find-common-ground.html.

d. South Korean Ministry of Unification, "National Community Unification Plan" [in Korean], www.unikorea.go.kr/unikorea/policy/plan.

e. During the Cold War, Finland maintained a realist strategy of neutrality between the West and the Soviet Union and “neighborly” relations with the

latter to coexist as a free and democratic country. The original use of the term Finlandization, however, suggested pejoratively that the country re-

linquished some aspects of its national sovereignty as a part of this arrangement. See James Kirchick, “Finlandization Is Not a Solution for Ukraine,”

The American Interest, July 27, 2014, www.the-american-interest.com/2014/07/27/finlandization-is-not-a-solution-for-ukraine.

Box 1.

13

USIP.ORG

Previous US policy toward North Korea may have

also been influenced by the belief that the Kim

regime would not endure indefinitely. The potential

for regime collapse or change was a consideration,

albeit small, for the Clinton, George W. Bush, and

Obama administrations that may have contributed

to an unwillingness to consider the regime as a truly

permanent entity requiring long-term relations and

peaceful coexistence.

The Trump administration has prioritized North Korea

as a top security concern and adopted a more aggres-

sive and urgent approach to peace and denucleariza-

tion than those of previous administrations. Under the

first prong of its “maximum pressure and engagement”

policy, the administration threatened military action

against North Korea through “fire and fury” and “bloody

nose strikes,” and significantly increased the number

of North Korean sanctions designations in an eort to

increase leverage.

23

By the June 2018 Singapore Summit, however,

President Trump shifted toward an accelerated en-

gagement approach. He minimized preconditions

for talks, met directly with Chairman Kim (three times

in thirteen months) despite the lack of regular work-

ing-level meetings, exchanged letters with him, provid-

ed significant concessions up front with little delibera-

tion (such as suspending the August 2018 joint military

exercise), and demonstrated a willingness to pursue

peace and denuclearization simultaneously rather

than sequentially. These steps have put North Korea’s

sincerity about denuclearization to the test.

At the same time, other aspects of the administration’s

policy implementation, including uneven Alliance

coordination, internal disunity, and disjointed messag-

ing, warrant significant concern and may be osetting

any potential gains. In particular, the insistence by

high-ranking ocials that North Korea disarm unilater-

ally before Washington provides any sanctions relief

continues to hinder US-DPRK negotiations.

a mutually agreeable, soft-landing

unification. Other experts argue that

a peace regime process would pre-

maturely relieve pressure on the Kim

regime to denuclearize and conduct

reforms, thereby extending it. From

this perspective, a peace regime

creates a strategic dilemma with no

clear resolution.

Assuming reunification is possible,

what a unified Korea might mean for

regional stability is also a matter of

concern. Washington supports the

peaceful reunification of Korea based

on the principles of free democracy

and a market economy. Yet some

Washington analysts believe that

South Korea, in its pursuit of reuni-

fication, may be willing to abandon

the US-ROK Alliance and assume

neutrality or, even worse, accommo-

date China’s foreign policy prefer-

ences under a Finlandization model.

e

Such concerns are even greater in

Tokyo, which worries that a neutral

unified Korea would be anti-Japan,

tilt toward China, reduce US influ-

ence and presence in the region,

and degrade Japan’s security vis-à-

vis China. For its part, Beijing could

accept a peacefully reunified Korea

but would oppose the continuation

of the Alliance and any eort to draw

Korea into a US containment strategy

against China. Mitigating these con-

cerns about the future orientation of

a reunified Korea will be an important

aspect of the peace process.

14

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

CHINA

China’s approach toward a peace regime is grounded

in its core priorities for the Korean Peninsula, which

Chinese ocials have described as no war, no instability,

and no nuclear weapons. Beijing seeks first to avoid

military escalation on the Korean Peninsula as well as

regime collapse in North Korea, both of which would

destabilize its immediate neighborhood. To a lesser

extent and as a longer-term goal, it also seeks North

Korea’s denuclearization to reduce proliferation and

contamination risks, curtail the rationale for US force

presence and military buildup in the region, and prevent

South Korea and Japan from seeking their own nuclear

weapons. It supports peace negotiations because they

would advance each of these three priorities.

It is also driven by its desire to maintain and project

influence on the Korean Peninsula. Beijing expects to

be involved as a major player in any peace process, not

only because of China’s role in the Korean War but also

because of the geostrategic implications for the future of

the region. In particular, Beijing seeks to take part in both

an end-of-war declaration and a formal peace treaty,

but especially the latter given that China was an original

signatory to the Armistice Agreement and wants to be

involved in shaping any final, legally binding agreement

that aects the future of the Korean Peninsula.

China has made this position clear not only in words but

also in its actions. Despite years of frosty relations and

no contact between President Xi Jinping and Chairman

Kim, bilateral ties warmed up quickly as North Korea

announced a strategic shift from nuclear to economic

development and began engaging with the United

States and South Korea to coordinate summit-level

meetings. The unprecedented number of strategically

timed meetings between Kim and Xi since 2018 signals

China’s determination not to be left out.

Beijing has encouraged bilateral negotiations first

between Pyongyang and Washington, with each side

making reciprocal concessions. It supports the idea of a

dual suspension (that is, a freeze in major US-ROK military

exercises in exchange for a freeze in North Korean nucle

-

ar and missile tests) to reduce tensions and has called for

parallel track negotiations to advance denuclearization

and peace simultaneously. This position is consistent with

Pyongyang’s preference for a “phased and synchronous”

process with Washington. However, if US-DPRK negoti-

ations progress to a broader discussion about a future

security arrangement for the Korean Peninsula, including

a peace agreement, China would seek to participate.

As China advocates for North Korea’s demands for secu-

rity concessions from the United States and South Korea,

it will try to shift the balance of regional power in ways

that are favorable to its interests. It is likely to leverage

the peace regime process to advance its strategic aim

of eroding the US presence in the region. For example,

Beijing has endorsed Pyongyang’s broad call to “denu-

clearize the Korean Peninsula.”

24

Although neither North

Korea nor China has clearly defined the specific US-ROK

actions required to create a “nuclear-free zone” on the

Peninsula, it may include demands that Washington

retract its nuclear umbrella over South Korea, end the

deployment of US nuclear and strategic assets to the

Korean Peninsula, roll back any missile defense cooper-

ation with Seoul, and reduce or withdraw US troops from

the Peninsula. If North Korea (and voices in South Korea)

push for the “neutralization” of the Korean Peninsula,

and thus the abrogation of the US-ROK Alliance, China is

likely to support this position given its desire to reduce

the US presence and alliance network in Asia.

25

Beijing will reject a peace regime that it perceives as

harming its own security interests or places the burden

of providing security for the Korean Peninsula on China.

It is also likely to reject any security arrangement that

it perceives as tilting the region toward Washington. It

will likely oppose any US positive security guarantees

to North Korea or any eorts to integrate North Korea

or a unified Korean Peninsula into the US-led alliance

network. At the same time, Beijing is also unlikely to

extend its own positive security guarantees to the

15

USIP.ORG

Korean Peninsula beyond the strictly defensive terms

enumerated in China’s bilateral treaty with North Korea.

26

Chinese leaders insist that China is a “new type of great

power” uninterested in formal alliances. China has never

extended its nuclear umbrella over another country thus

far, and the provision of extended deterrence guaran-

tees to North Korea or other partners would require a

fundamental shift in China’s strategic thinking.

China, however, would likely support any economic

dimensions of a peace regime. Beijing views eco-

nomic engagement and partnerships as its primary

way to expand its relationships and influence with

partners. Beijing has long desired that Pyongyang

follow in China’s footsteps by opening up economically

while preserving its political system. Chinese leaders

believe North Korea’s economic development and

regional integration are key to stabilizing its immediate

neighborhood. They have therefore vowed to support

Kim’s strategic shift toward economic development,

including by proposing with Russia a plan for lifting UN

sanctions on North Korea related to exporting stat-

ues, seafood, textiles, and labor as well as exempting

inter-Korean railway projects from UN sanctions.

27

JAPAN

In the post–Cold War era, Japan’s relations with North

Korea have reflected Tokyo’s interest in increasing its

regional leverage relative to Beijing and Moscow while

enhancing its ability to act independently of Washington

and Seoul.

28

Japan has typically engaged in normaliza-

tion talks with North Korea during periods of inter-Kore-

an and US-DPRK rapprochement to avoid losing influ-

ence and to ensure that its interests are being served.

Between 1991 and 1992, it conducted eight rounds of

normalization talks with Pyongyang to establish ties

Commuters in the Seoul Railway Station watch a television showing North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, left, welcoming Chinese President Xi Jinping

to Pyongyang on June 21, 2019. (Photo by Lee Jin-man/AP)

16

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

and resolve outstanding claims from colonial Japanese

rule. These talks failed, however, over the issues of

international inspections of North Korea’s nuclear sites,

Japanese citizens abducted by North Korea during the

1970s and 1980s, and compensation for post–World War

II claims.

29

After North Korea conducted a Taepodong

missile launch over Japanese territory in 1998 and

appeared to be making diplomatic progress with

Washington and Seoul in 2000, Tokyo held additional

rounds of normalization discussions in 2000 and 2002.

Although these talks did not yield significant results, the

two sides agreed on a joint declaration in 2002 in which

North Korea admitted to abducting Japanese nationals

and Japan expressed remorse for its colonial past.

30

Since the 2002 declaration, successive Japanese admin-

istrations have prioritized two goals under its North Korea

policy: the elimination of North Korea’s weapons of mass

destruction, including its nuclear and ballistic missile

programs, and the resolution of the abductee issue. The

first goal overlaps with US objectives, though Tokyo is

concerned that Washington is overlooking Pyongyang’s

shorter-range missile capabilities while focusing on the

longer-range threat. In response to domestic public

opinion, Japan is also continuing to seek a full account-

ing of the remaining twelve Japanese abductees. In

recent years, the Shinzo Abe government has insisted on

a “comprehensive resolution” of these two issues as the

conditions for normalization of bilateral relations.

31

Japan’s rigid position on these issues, particularly abduct-

ees, may stem from a desire to influence the agenda de-

spite its limited role in nuclear negotiations. Some experts

have argued that stalled denuclearization negotiations

prolong the North Korean threat, which provides Japan

additional justification to enhance its military capabilities,

particularly in the context of a stronger China.

32

During

the Six-Party Talks, Japan was criticized for obstructing

progress by making stringent denuclearization demands

and conditioning its provision of economic and energy

assistance on a full resolution of the abductee issue.

33

During Pyongyang’s recent spate of diplomatic outreach,

Tokyo has been relegated to indirect involvement in the

form of consultations with Washington. Japan remains

the only country with significant interests on the Korean

Peninsula that has not had a leader-level meeting with

North Korea during this period. The Abe administration

has been willing to let President Trump lead the denu-

clearization negotiations given their aligned position on

North Korea policy, but in May 2019 began proposing an

unconditional bilateral summit with Kim to ensure that its

interests are not neglected.

Japan wants to be included in multilateral negotiations

that involve serious discussions about a future regional

security architecture. It also wants a security framework

that reduces the North Korean threat so that it can focus

resources on China, which it views as its primary long-

term strategic threat.

34

This view supports the continu-

ation of a robust US presence on the Korean Peninsula

and in the region. Some Japanese experts are con-

cerned, however, that eorts to reduce this posture, in-

cluding modifications to US-ROK military exercises, would

not only undermine military readiness and deterrence but

also elicit domestic complaints about why similar meas-

ures could not be taken to decrease US forces in Japan.

Japan’s ability to provide economic assistance can be

useful in peace and denuclearization discussions. Tokyo

continues to adhere to the understanding in the 2002

declaration that Japan will provide grant aid, low interest

loans, and humanitarian assistance to North Korea as

part of the normalization process, similar to the compen-

sation given to the South as part of the 1965 Japan-ROK

normalization treaty. Estimates of the compensation

amount, adjusted for inflation and accrued interest,

range from $10 to $20 billion.

35

However, Tokyo wants to

Tokyo wants to have a role in shaping security discussions rather than being asked to simply provide a

blank check. Japan may have to shed its spoiler role if it is to have a greater role in a peace regime process.

17

USIP.ORG

have a role in shaping security discussions rather than

being asked to simply provide a blank check.

Japan may have to shed its spoiler role if it is to have a

greater role in a peace regime process. In addition, its

current dispute with South Korea regarding historical,

export control, and security issues, if not resolved, could

complicate future multilateral negotiations as well as

Japan-DPRK normalization eorts. If US-DPRK and in-

ter-Korean negotiations advance in the future without ac-

ceptable resolutions to the abductee and ballistic missile

issues, Japan will need to decide whether it can maintain

its long-standing position or risk losing leverage on the

Peninsula and in bilateral Japan-DPRK negotiations.

RUSSIA

Like Beijing, Moscow favors North Korea’s denucleariza-

tion and the de-escalation of tensions through political

dialogue but is skeptical about the Kim regime’s will-

ingness to give up its nuclear weapons.

36

Russia also

worries that North Korea’s nuclear program heightens a

multitude of risks, including military conflict, regime insta-

bility, the erosion of the global nonproliferation regime,

contamination from nuclear accidents, and US military

expansion in the region. Based on these concerns, its

historical ties with North Korea, and its limited leverage in

the region, Moscow has typically mirrored Pyongyang’s

and Beijing’s prescriptions—such as the “dual freeze”

proposal—and their criticisms of US demands for North

Korea’s immediate and unilateral denuclearization. In

October 2018, at a trilateral vice foreign ministers meet-

ing in Moscow, Russia joined China and North Korea in

supporting a negotiations process that includes step-by-

step, reciprocal measures, a peace mechanism based on

bilateral and multilateral cooperation, and an easing of

the sanctions regime against North Korea.

From a broader perspective, Russia’s Korea policy re-

flects its geopolitical strategy for relations with other ma-

jor powers and sustaining its claim to great power status

in the region. Cooperation on North Korea policy is a key

issue for the deepening Sino-Russian “comprehensive

strategic partnership of coordination.”

37

Both powers

hope to use the peace and denuclearization process to

weaken the US-ROK Alliance and undermine the US-led

regional security architecture. At the same time, Moscow

recognizes that China’s stake in Korea is bigger than

Russia’s, and therefore shows a certain deference to

Beijing in dealing with Korea.

Russia also seeks, however, to maintain regional

influence and avoid acquiescing to China in Peninsula

diplomacy. The April 2019 Putin-Kim summit demonstrat-

ed Moscow’s ability to engage North Korea directly as

a way of gaining strategic leverage vis-à-vis the United

States.

38

President Putin has also called for Russia to

“turn to the East” and deepen its involvement in the

Asia-Pacific overall.

39

Staying involved in Korea, even

if not decisively, supports Moscow’s regional goals. It

also envisions itself playing a helpful role in a broader

discussion about security mechanisms in Northeast Asia.

It expects a peace regime to include a series of bilateral

and multilateral security guarantees covering the entire

Peninsula, which would then form the foundation for a

new regional security mechanism—presumably one with

a diminished US role. In addition, experts note that, in

the context of the collapse of the Intermediate-Range

Nuclear Forces Treaty and the potential for a regional

missile arms race, Russia could facilitate discussions

among regional actors on strategic missile systems.

40

Economics and trade are also major drivers of Russia’s

Korea policy. Moscow wants to develop the Russian Far

East, link South Korean railroads to the Trans-Siberian

Railway, and grow demand for its energy exports to

Asia by connecting pipelines and electricity systems

with the Peninsula. These interests align well with

President Moon’s hopes of using regional economic

cooperation to persuade North Korea to intensify its

shift from nuclear to economic development. Easing

sanctions on North Korea—which Russia helped adopt

as a permanent member of the UN Security Council

but has only selectively enforced—would remove an

economic constraint for both countries.

18

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

Structure of a Peace Regime

Various terms have been used to describe a complete

and enduring settlement of the Korean War, but ocial

bilateral and multilateral statements since the September

2005 Joint Statement of the Six-Party Talks have ex-

plicitly articulated a peace regime as a primary goal.

Recognizing that peace is not a singular event that can

be achieved by one accord, the South Korean gov-

ernment oered the concept of a peace regime as an

organizing structure. The concept has since developed

to encompass a comprehensive framework of declara-

tions, agreements, norms, rules, processes, and institu-

tions—spanning the diplomatic, security, economic, and

social spheres—aimed at building and sustaining peace

on the Korean Peninsula (see table 1). Under this broad

definition, a peace regime would encompass previous

inter-Korean, US-DPRK, and multilateral declarations as

well as any future measures, including an end-of-war

declaration, any bilateral or multilateral peace processes

designed to achieve a final agreement, the peace agree-

ment itself, and any subsequent organizations, mecha-

nisms, or frameworks designed to maintain the peace.

Two important components of a peace regime—an end-

of-war declaration and a peace treaty—are often conflat-

ed. The Moon Jae-in administration envisions an end-

of-war declaration as a symbolic, nonbinding, political

statement that proclaims the Korean War to be over and

that marks the beginning of a new era of peaceful rela-

tions.

41

These new relations could also be demonstrated

through security guarantees, partial sanctions relief, the

exchange of liaison oces, reduced military tensions,

and people-to-people exchanges. To reinforce the lack

of any legal eect, the statement would underscore that

existing arrangements that maintain the peace, such as

the UN Command, the Armistice Agreement, and the

Military Demarcation Line, would remain in place until

the parties negotiate a more comprehensive peace

settlement.

42

The broader settlement, achieved under

a formal peace treaty, would require extensive negotia-

tions to replace the Armistice Agreement, formally end

the Korean War, complete the process of denucleariza-

tion, and create a binding set of obligations for maintain-

ing peace and security on the Peninsula. In this sense,

an end-of-war declaration would essentially serve as a

preamble to a peace agreement.

A comprehensive peace regime should address three

separate, but interrelated, sets of unresolved issues

from the Korean War: the multilateral nature of that war

and a long-term security architecture for the Korean

Peninsula and the region; the civil war and reconcilia-

tion between the two Koreas; and the normalization of

relations between the United States and North Korea

and between Japan and North Korea.

First, an umbrella peace agreement could be used to set-

tle the wider multilateral issues related to formally ending

the Korean War and establishing peace on the Korean

Peninsula. These issues would include the cessation of

hostilities, the status of foreign conventional and strategic

forces on the Peninsula, North Korea’s weapons of mass

destruction programs, the replacement of the Armistice

Agreement, human rights, the role of the United Nations,

and the establishment of both transitional and permanent

systems for managing the peace on the Peninsula and in

the region. The multilateral dimension of a peace agree-

ment should also lay the foundation for regional stability

by securing buy-in and support for a permanent Korean

peace from the United States and China.

Second, a separate process—perhaps annexed under

the umbrella agreement—would formally end the war

19

USIP.ORG

between the two Koreas and resolve additional inter-

Korean issues, including outstanding border and terri-

torial matters, such as the Northern Limit Line (NLL) and

the Northwest Islands; military tension reduction; eco-

nomic cooperation; the movement of people, goods, and

services across the border; and any guidelines for future

confederation or reunification. The United States will

likely play a role given its combined defense posture with

South Korea and its role through the UN Command in es-

tablishing the NLL and controlling the Northwest Islands.

Previous inter-Korean agreements, such as the 1972

North-South Joint Statement, the 1991 Basic Agreement,

and the 2018 Comprehensive Military Agreement, have

already delineated principles and steps for reconciliation

and tension reduction that can serve as a foundation for

the new inter-Korean agreement.

Examples

Declarations,

Agreements,

and Statements

(past and future)

• July 1972 South-North Joint Communique

• December 1991 Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, and Exchanges and Cooperation

between the South and North

• January 1992 Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula

• June 2000 North-South Joint Declaration

• October 2000 US-DPRK Joint Communique

• October 2007 Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Korean Relations, Peace and Prosperity

• June 2018 Singapore Statement

• Potential end-of-war declaration

• Potential peace agreement or treaty

Norms, Rules,

and Processes

• Secretary Tillerson “Four No’s” (no regime change, no regime collapse, no accelerated reunification of

the Korean Peninsula, and no US forces north of the 38th parallel)

• Four pillars of Singapore Statement (new US-DPRK relations, lasting and stable peace regime on the Korean

Peninsula, complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, commitment to recovering POW/MIA remains)

• President Moon Sunshine Policy (two Koreas must play leading role on Peninsula and unification

issues, peaceful coexistence of two Koreas, no intent for collapse or absorption of North Korea,

denuclearization of the Peninsula, permanent peace regime, inter-Korean economic cooperation,

nonpolitical exchange and cooperation separate from political matters)

• Chairman Kim-President Xi policy (“phased and synchronous measures” that would “eventually achieve

denuclearization and lasting peace on the peninsula”)

• China’s support for “dual freeze” on North Korean nuclear and missile tests and US-ROK joint military

exercises and parallel track negotiations on peace and denuclearization

• Japan’s policy (resolution of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles and Japanese

abductee issue)

• Potential institutionalized peace process

Institutions • Potential peace management organization (to replace Military Armistice Commission)

• Inter-Korean joint military committee

• Potential US-DPRK senior-level military-to-military dialogue

• Potential bilateral, four-party, and six-party working groups

• Potential regional security mechanisms (for example, Northeast Asia Peace and Security Mechanism)

Table 1. Conceptual Framework of a Korean Peninsula Peace Regime

20

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

Finally, separate tracks would be needed to

normalize Pyongyang’s relations with both

Washington and Tokyo. Establishing US-

DPRK diplomatic relations could be relatively

quick and simple once major issues such as

denuclearization, sanctions relief, and human

rights were resolved in multilateral discus-

sions. Also, although Japan was not a bel-

ligerent in the Korean War, its role as a base

for US and multinational forces during the

conflict and as a major power in the region

makes Japan-DPRK normalization an impor-

tant part of the peace regime process. Other

bilateral aspects of the Korean War, such as

the prior state of conflict between the United

States and China, and between the ROK and

China, have already been resolved through

the normalization of diplomatic relations in

1979 and 1992, respectively.

A Korean Peninsula peace regime compris-

es a broad set of interrelated diplomatic,

security, and economic challenges (see

table 2). Certain sensitive issues (such as

denuclearization and sanctions relief) are

linchpins to the entire endeavor; others

would be important confidence-building

measures (an end-of-war declaration, hu-

manitarian assistance, and so on). Similarly,

some measures are better suited to the

front end of the process. Others would

come only later, as the process ripens.

Ultimately, as the perspectives of the in-

volved countries make clear, most if not all

of these issues must be addressed at some

point in the peace regime process.

POTENTIAL MEASURES

UNDER A PEACE REGIME

SHORT TERM (temporary or reversible measures)

Establishment of working groups on peace and

normalization (US-DPRK, JPN-DPRK), setting of

diplomatic end states

End-of-war declaration

Liaison oces

End of travel ban to and from North Korea

People-to-people exchanges (POW/MIA remains recovery

operations, reunion of divided families, cultural exchanges)

Intermittent head-of-state meetings for progress updates

Broad DPRK commitment to engage on human rights,

initial human rights measures, meetings with UN special

rapporteur and US special envoy

Partial sanctions relief, with snapback provisions and

focus on inter-Korean projects or limited sectors (such as

Kaesong Industrial Complex, Mount Geumgang tourism,

coal and textile)

Support for technical assistance related to economic

reform and international financial institution (IFI)

requirements

Humanitarian assistance

Commitment to discuss economic and energy assistance

DPRK commitment to address counterfeiting and money

laundering

Establishment of four-party working group on

denuclearization and security (US-DPRK-ROK-PRC),

definition of denuclearization of Korean Peninsula

Mutual negative security assurances

Moratorium on nuclear and ballistic missile tests

Freeze on all nuclear and ballistic missile activities

Declaration of nuclear activities related to Yongbyon

Yongbyon shutdown and return of monitors and inspectors

Engagement on cooperative threat reduction measures

Development of inter-Korean joint military committee

Development of additional arms control, military tension

reduction measures

Suspension or modification of large US-ROK military

exercises and Korean People's Army (KPA) exercises

Halt to deployment of US strategic and nuclear assets on

or near Korean Peninsula

Establishment of US-DPRK military-to-military dialogue

DIPLOMATIC

ECONOMIC

SECURITY

Table 2.

21

USIP.ORG

LONG TERM

Regular working-level meetings on peace and

normalization, including human rights norms

Continued people-to-people exchanges

Intermittent head-of-state meetings for progress updates

Continued DPRK engagement on human rights measures

and periodic reviews

Signing of four-party peace agreement, including DPRK

human rights commitments

Normalization of relations

Establishment of embassies

Continued review of peace agreement implementation

Increased people-to-people exchanges

Intermittent head-of-state meetings for progress updates

Continued implementation of DPRK human rights

commitments and periodic reviews, including termination

of gross violations

Additional sanctions relief with snapback provisions,

commensurate with DPRK actions

Removal from state sponsor of terrorism list

Continued humanitarian assistance

Discussion of energy assistance

Complete sanctions relief commensurate with

denuclearization, with snapback provisions

Continued support for economic reform and international

financial institutions membership

Continued economic and energy assistance

Continued humanitarian assistance

Regular four-party working-level meetings on

denuclearization and security

Complete and verifiable dismantlement of Yongbyon facility,

partial verification of halt to uranium enrichment activities

Declaration of all nuclear and missile activities

North Korea accedes to the Chemical Weapons Convention

Continued engagement on cooperative threat reduction

measures

Proportional US-ROK and DPRK conventional force

reduction measures

Suspension or modification of large US-ROK military

exercises and KPA exercises

Continued halt to deployment of US strategic and

nuclear assets on or near Korean Peninsula

US force presence commensurate with security environment

Begin six-party working group on regional security

(US-DPRK-ROK-PRC-JPN-RUS)

Continued verification of halt to all uranium enrichment

Verified dismantlement of all nuclear weapons

Verified dismantlement of intermediate-range and long-

range ballistic missiles

Elimination of DPRK chemical weapons

Continued engagement on cooperative threat reduction

Disestablishment of United Nations Command

Establishment of new peace management organization

Resolution of NLL and Northwest Islands issues

Proportional US-ROK and DPRK conventional force

reduction measures

Suspension or modification of large US-ROK military

exercises and KPA exercises

Continued halt to deployment of US strategic and

nuclear assets on or near Korean Peninsula

US force presence commensurate with security environment

Establishment of six-party regional security mechanism

MEDIUM TERM

DIPLOMATIC

DIPLOMATIC

ECONOMIC

ECONOMIC

SECURITY

SECURITY

22

PEACEWORKS | NO. 157

Diplomatic Issues

Constructing a peace regime on the Korean Peninsula

would require a series of diplomatic actions from sev-

eral parties. In particular, Washington and Pyongyang

would need to transform their ties from near-total es-

trangement into normalized relations. This would need

to begin with ending the state of conflict that has exist-

ed since the beginning of the Korean War in 1950 and

was frozen in place by the 1953 Armistice Agreement.

One approach, which South Korea has suggested,

would be for the parties to formally conclude fighting in

two steps. First, the United States, South Korea, North

Korea, and potentially China could issue an end-of-war

declaration, which would amount to a political rather

than legal statement that all the parties consider hostil-

ities terminated. The second step would create a pro-

cess to replace the armistice with a peace agreement.

Such a process would be much more dicult given the

large set of issues involved and the potential legal con-

sequences of terminating the armistice. It would likely

entail various interim steps or agreements that achieve

prerequisite confidence-building measures prior to a fi-

nal settlement (for example, an interim deal that freezes

North Korea’s nuclear and missile activities in exchange

for security guarantees and economic assistance).

The normalization of diplomatic relations by itself could

potentially come before a final peace agreement and be

relatively easy to achieve if the countries involved agree

to it. For example, Japan and Russia share diplomatic

and economic ties despite the lack of a formal peace

treaty after World War II. However, that sequence would

be politically dicult for the United States unless signifi-

cant progress is made on North Korean denuclearization

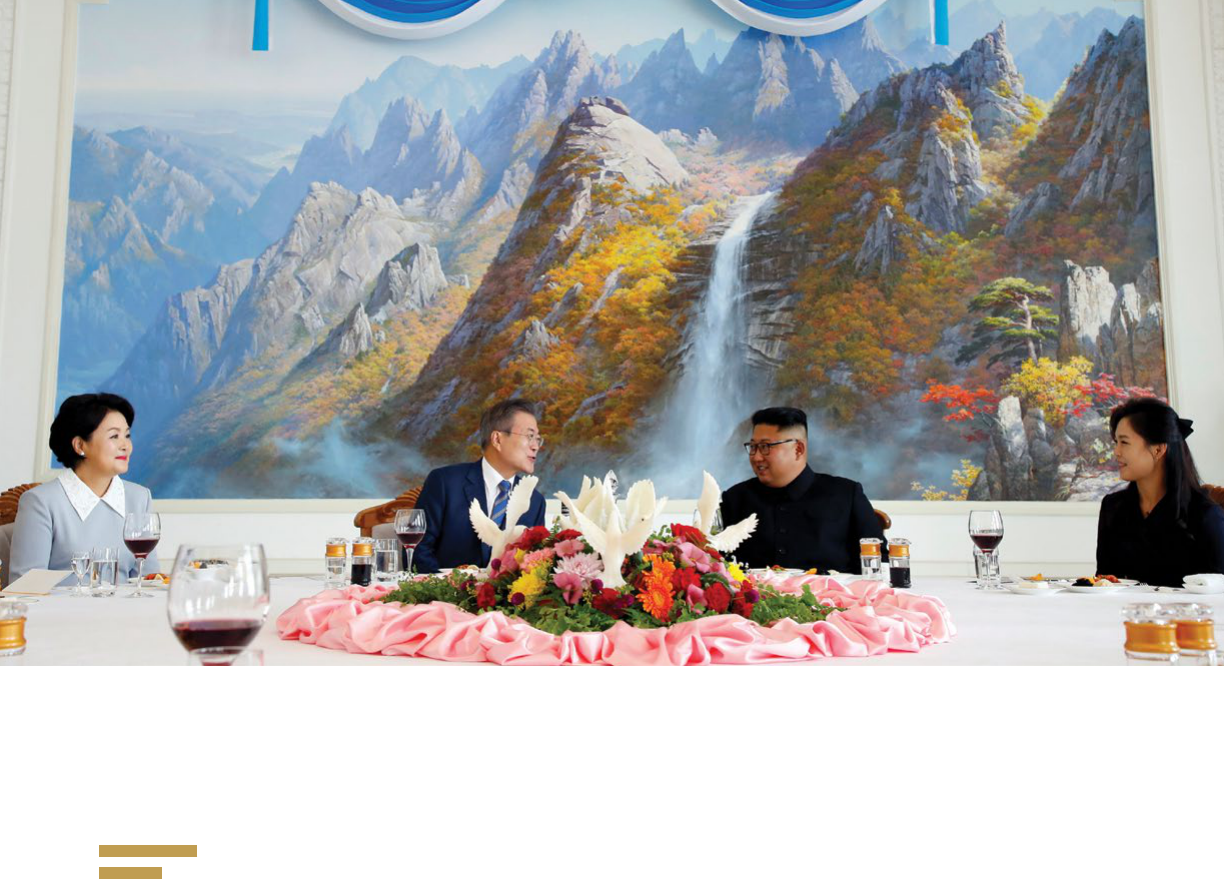

President Moon Jae-in of South Korea and Kim Jong Un of North Korea, flanked by their spouses, during a luncheon in Pyongyang during their Sep-

tember 2018 summit. (Photo by Pyeongyang Press Corps Pool via New York Times)

23

USIP.ORG

and human rights. A process that addresses denucleari-

zation and peace in parallel would have the best chance

of maintaining political support from all sides.

Questions about which parties have the authority to

act on behalf of the belligerents remain. The armistice

was signed by the UN Command; the Korean People’s

Army (KPA), North Korea’s military; and the People’s

Volunteer Army, a now-defunct military force Beijing

created solely to fight in Korea. It is therefore unclear

whether the United States can sign on behalf of the

United Nations, whether South Korea can sign at all,

and whether the unocial status of the former People’s

Volunteer Army allows Beijing to sign a subsequent

agreement on its behalf.

43

Legal analyses have argued

that both Koreas, the United States, and China could

justifiably sign an agreement to replace the armistice.