S S Q ♦ F 2017 95

Nuclear Arms Control:

A Nuclear Posture Review Opportunity

Stephen J. Cimbala

Abstract

US nuclear posture includes national priorities for nuclear arms control.

One important issue for the Trump administration is the possibility of

extending or revising the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START)

of 2010 that goes into eect in 2018 and expires in 2021. e analysis

that follows compares outcomes from New START and lower numbers

of deployed weapons for the United States and for Russia, in terms of

their implications for deterrence and arms control stability. e signi-

cance of missile defenses in this context is also addressed, since Russia

has dened US missile defenses as destabilizing with respect to nuclear

arms control and potentially nullifying of Russia’s nuclear deterrent.

✵ ✵ ✵ ✵ ✵

Vladimir Putin’s third term as Russian president conicted with the goals

of Barack Obama’s second term as US president. As a result, US-Russian

political relations were mired in negativity, precluding the possibility of any

follow-up agreement to the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty of

2010.

1

If relations between the two countries eventually improve, should

America and Russia extend New START or, with more ambition, seek

post–New START reductions in their numbers of operationally deployed

long-range nuclear weapons and launchers? is question must be considered

part of the current US Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). e discussion that

follows addresses this issue in four steps: (1) where things stand now,

(2) options for strategic nuclear arms reductions, (3) the implications of

missile defenses for nuclear strategic stability, and (4) conclusions and

related discussion.

Stephen J. Cimbala is a distinguished professor of political science at Penn State–Brandywine and

author of numerous works on national security, nuclear arms control, deterrence, and missile defense.

His most recent book is Nuclear Weapons in a Multipolar World (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Stephen J. Cimbala

96 S S Q ♦ F 2017

Nuclear Stasis

More than two and one-half decades after the end of the Cold War

and the demise of the Soviet Union, post-Soviet Russia and the United

States maintain numerous nuclear weapons deployed on intercontinental

and transoceanic launchers, including land-based intercontinental bal-

listic missiles (ICBM), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM),

and heavy bombers capable of carrying a variety of munitions, includ-

ing gravity bombs, air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM), and advanced

cruise missiles. Even after complying with the reductions called for in

the New START agreement signed by presidents Obama and Medvedev

in 2010, Russia and the United States will deploy a maximum number of

1,550 long-range or “strategic” nuclear weapons on a maximum of 700

deployed intercontinental launchers.

2

In addition, a signicant number

of each state’s strategic nuclear weapons will require prompt launch for

survivability, increasing the risk of nuclear instability in time of crisis.

It would be an understatement to say that the current nuclear relation-

ship between the United States and the Russian Federation is an historical

and strategic anomaly. eir nuclear arsenals remain sized in relation

to each other and directly pointed at one another despite the fact that,

were nuclear crisis management and deterrence to fail, no acceptable

outcome to any nuclear war between the United States or NATO and

Russia is foreseeable.

3

To be sure, former President Obama’s national

security strategy and nuclear policy documents indicated that, so long

as nuclear weapons existed anywhere, the United States would maintain

a nuclear force and supporting infrastructure second to none. And he

was right: with nuclear weapons, blung is a dangerous game. States

that want to play this game need to know, and their enemies must know,

that their nuclear deterrent is safe, secure, reliable, and proof against

either of two kinds of error. First, the US nuclear deterrent should be

promptly responsive to duly authorized commands for nuclear retalia-

tion after having been attacked—but the United States must not launch

a nuclear retaliatory attack on a mistaken premise that an enemy has

already launched a nuclear rst strike. Second, US nuclear weapons also

provide “extended deterrence” for American allies and, in so doing, sup-

port global nonproliferation by limiting those states’ vulnerability to

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 97

nuclear coercion and/or attack, and thus reducing their incentives to

become nuclear-weapons states.

How many weapons are needed to satisfy these criteria is an arguable

question. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States and Russia

have downsized their nuclear arsenals considerably. e New START

limitations (1,550 deployed weapons on 700 deployed intercontinental

launchers) for each state are a long way from the tens of thousands of

deployed weapons that marked the height of the Cold War. Politically

the United States and Russia have convergent and divergent interests.

On the one hand, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and continuing

destabilization of eastern Ukraine have provoked NATO responses that

include larger US and allied force deployments in Eastern Europe, includ-

ing in states bordering Russia, as well as having boosted American and

allied expenditures for conventional defense in Europe.

4

On the other

hand, Russia and the United States have at least partly overlapping and

congruent interests in defeating terrorism, in a stable post-NATO

Afghanistan, and in preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to rogue

states or nonstate actors, including terrorists. In Europe, NATO seeks

to maintain a spectrum of deterrent and defense capabilities to forestall

aggression, to prevail in a conventional war if necessary, and to deter

nuclear rst use. NATO also faces the challenge of Russian hybrid war-

fare, including nonkinetic components such as cyberwar, active mea-

sures, disinformation, and varieties of inuence operations. Although

it is hoped that neither hybrid nor conventional warfare would escalate

beyond the nuclear threshold, US strategic nuclear forces and other

nuclear weapons deployed on the territories of NATO allies support

NATO’s mission as being capable of deterring and resisting aggression

at all levels. NATO requires this exibility because, as military planners

well know and history teaches, states often get the wars that they did not

plan for or expect.

Granted, Russia maintains its strategic and shorter range nuclear forces

for political and military reasons other than those having to do with its

relations with the United States and NATO. Russia enjoys the cachet and

spillover diplomatic suasion of being a nuclear superpower treated as an

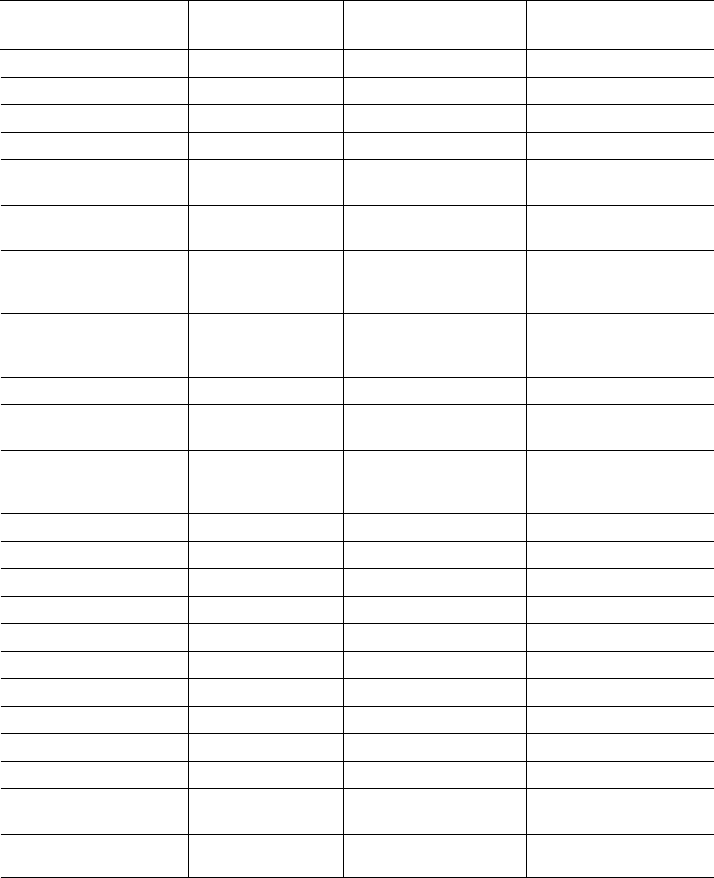

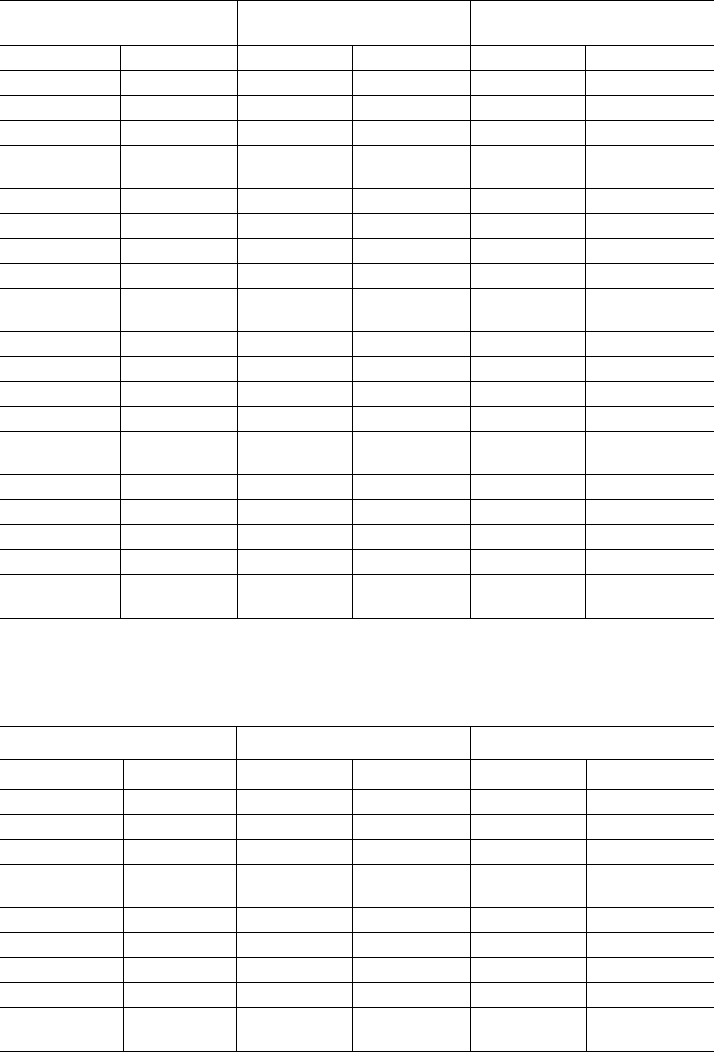

equal by the United States in nuclear arms control. Tables 1 and 2 sum-

marize Russian and American strategic nuclear forces in 2016.

Stephen J. Cimbala

98 S S Q ♦ F 2017

Table 1. Russia strategic nuclear forces, 2016

Type Launchers

Warheads

per launcher

Total

warheads

ICBM

a

SS-18 46 10 460

SS-19 20 6 120

SS-25 90 1 90

SS-27 Mod. 1

(mobile)

18 1 18

SS-27 Mod. 1

(silo)

60 1 60

SS-27 Mod. 2

(mobile)

(Russian RS-24)

63 4 252

SS-27 Mod. 2

(silo)

(Russian RS-24)

10 4 40

RS-26 Yars-M 0 0 0

SS-27 Mod.

(rail mobile)

0 0 0

SS-XX “heavy”

(silo)

(RS-28 Sarmat)

0 0 0

Subtotal ICBM 307 27 1,040

SLBM

b

SS-N-18 2/32 3 96

SS-N-23 6/96 4 384

SS-N-32 3/48 6 288

Subtotal SLBM 11/176 13 768

Bombers/weapons

Bear-H6 27 6

c

162

Bear-H16 30 16

c

480

Blackjack 13 12

d

156

Subtotal

bombers/weapons

70 34 798

Total 553 74 ~2,600

e

Source: Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2016,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 72, no. 3 (2016):

125–34, http://doi.org/f8n4ft. See also Arms Control Association, “Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces under New START,” October

2016, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Russian-Strategic-Nuclear-Forces-Under-New-START.

Note: e following key applies also to tables 2–8.

a

Intercontinental ballistic missile

b

Submarine-launched ballistic missile

c

Air-launched cruise missile (ALCM), bombs

d

ALCMs, short-range attack missiles (SRAM), bombs

e

About 1,800 warheads are actually deployed on missiles and at bomber bases. Bombers carry three kinds of weapons: ALCMs,

gravity bombs, and SRAMs air-to-ground. Also, under New START counting rules, each bomber counts as a single warhead.

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 99

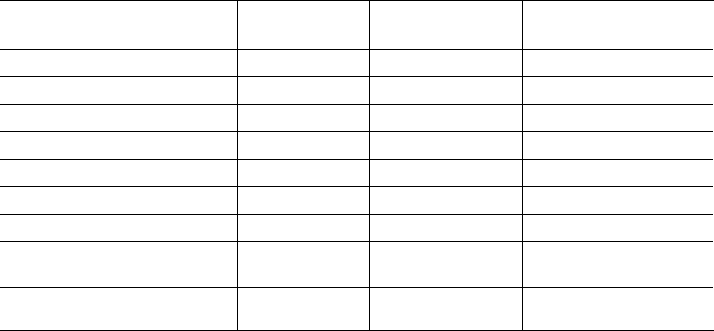

Table 2. US strategic nuclear forces, 2016

Type Launchers

Warheads

per launcher

Total

warheads

ICBM

Minuteman III 440 1 440

SLBM

Trident II D5 288 4 1,152

Bombers/weapons

B-52H 44

a

–—

b

200

B-2A 16

a

–—

b

100

Subtotal

bombers/weapons

60 300

Total 788 ~5 1,892

Source: Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2016,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 72, no. 2

(2016): 63–73, http://doi.org/b8zj. See also Arms Control Association, “U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces under New START,” October

2016, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/USStratNukeForceNewSTART.

a

Counts only primary mission aircraft tasked for nuclear missions

b

US bombers can deliver variable mixes of air-launched cruise missiles and gravity bombs, depending on mission.

In military terms, Russia’s conventional (nonnuclear) forces are vastly

inferior to those of the former Soviet Union and to those currently de-

ployed by the United States and NATO. Although members of the

alliance assume a NATO military attack on Russia is inconceivable, Rus-

sians fear that an imbalance in usable military power between NATO

and Russia reduces Russia’s military shadow over contestable parts of the

former Soviet space that Moscow regards as a zone of privileged interest.

5

In addition, although Russian ocials rarely speak of it in public, Russia

cannot help but notice the increasingly competent and “wired” military

of the People’s Republic of China and its higher prole in support of

China’s expanded denition of its interests in Asia and elsewhere.

6

But Russia would be mistaken to assume that nuclear weapons can,

in the long run, compensate for deciencies in its conventional armies,

navies, and air arms of service. Leading Russian military thinkers have

acknowledged the need for comprehensive military reform in everything

from manpower policy to weapons modernization.

7

Russia’s own docu-

mented interests in military cyberwar, together with its abysmal perfor-

mance in the war against Georgia in 2008, are only two indicators of its

recognition that nuclear weapons cannot resolve most of the outstand-

ing security issues in Russia’s favor.

8

Sooner or later, nuclear cover for

conventional military weakness falls at because nuclear weapons are

uniquely blunt weapons of mass destruction, not weapons for prevailing

Stephen J. Cimbala

100 S S Q ♦ F 2017

in combat at an acceptable cost. erefore, Russia’s putative case, that

tactical nuclear weapons can be used for “de-escalation” of a conict to

Russia’s advantage that would otherwise pose an unacceptable loss of

territory or sovereignty, is an example of military doublethink.

9

is

implies, or logically leads to, the following conclusion: Russian nuclear

weapons, like those in America, will continue to be seen as a last-ditch

option in peacetime and crisis by decision-makers with the practical

eect that, unlike in the Cold War, their main utility is deterring each

other rather than truly being tied tightly and seamlessly to a chain of

promised escalation like that seen in US and Russian postures in the

Cold War.

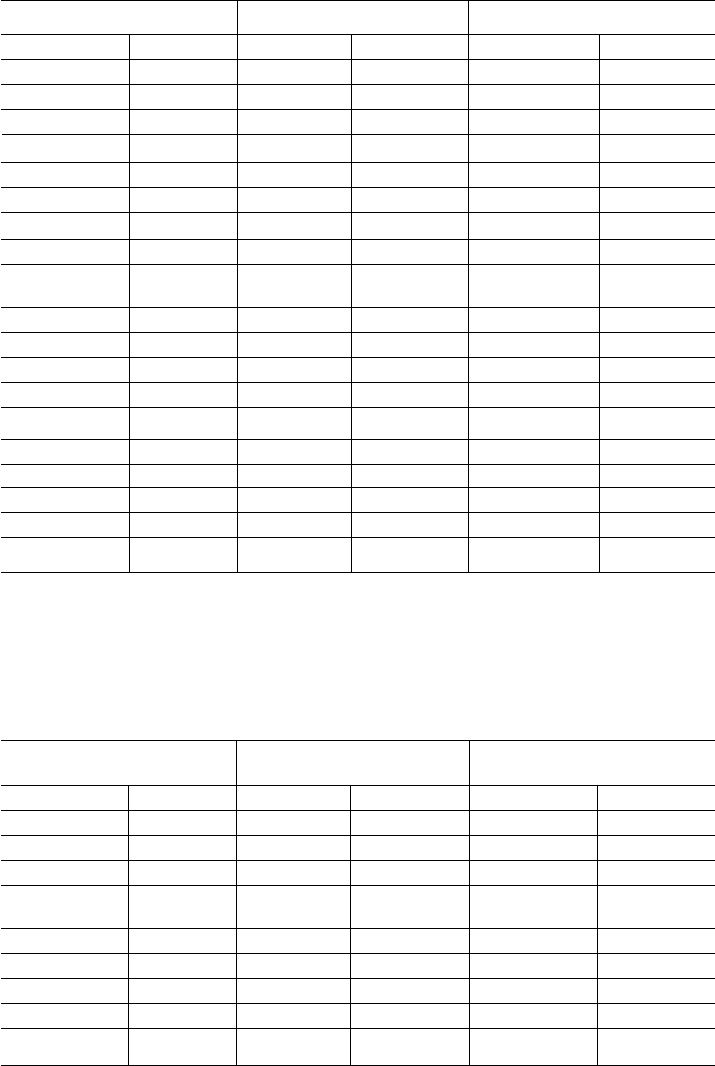

Options for Reductions

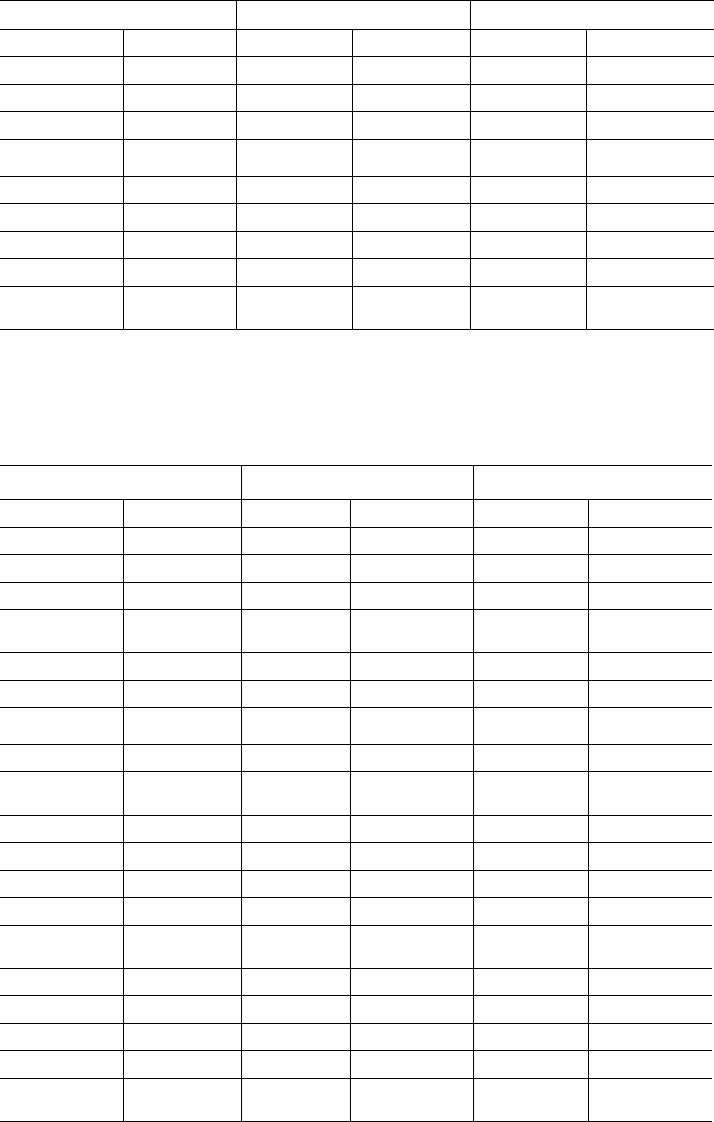

What do the preceding arguments suggest about the actual numbers

of strategic nuclear weapons the United States and Russia might require

for credible deterrence within the 2018–2021 time frame?

10

Tables 3

through 7 illustrate some benchmarks by which one could measure the

deterrence stability and military viability of US and Russian long-range

nuclear forces. e tables summarize the outcomes of nuclear force ex-

changes for the United States and Russia under four assumptions about

operational deployments.

11

Tables 3 and 4 assume future Russian and

American forces with maximum deployment limits as agreed under New

START (1,550 weapons counted under New START rules). For com-

parison, tables 5 and 6 assume post–New START reductions to a lower

maximum limit of 1,000 deployed weapons. In tables 7 and 8, each state

is limited to a hypothetical force structure with a maximum limit of 500

operationally deployed weapons on transcontinental launchers.

12

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 101

Table 3. US nuclear exchange outcomes (1,550 deployment limit)

Type US New START 1,550 Balanced triad

GEN

a

—LOW

b

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM

420 420 420 420 378

SLBM

1,064 958 958 958 862

Bombers

48 43 43 43 35

All 1,532 1,421 1,421 1,421 1,275

GEN—ROA

c

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM

420 420 420 42 38

SLBM

1,064 958 958 958 862

Bombers

48 43 43 14 11

All 1,532 1,421 1,421 1,014 911

DAY

d

—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM

420 420 420 420 378

SLBM

1,064 958 642 642 577

Bombers

48 43 0 0 0

All 1,532 1,421 1,062 1,062 955

DAY—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM

420 420 420 42 38

SLBM

1,064 958 642 642 577

Bombers

48 43 0 0 0

All 1,532 1,421 1,062 684 615

Note: e following key applies to tables 3–8.

a

Generated alert of full nuclear force (available)

b

Launch on warning

c

Ride out attack

d

Day-to-day forces on nuclear alert

Table 4. Russia nuclear exchange outcomes (1,550 deployment limit)

Type

Russia

New START 1,550 Balanced triad

GEN—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM

542 542 542 542 488

SLBM

640 576 576 576 518

Bombers

76 68 68 68 55

All 1,258 1,186 1,186 1,186 1,062

GEN—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 542 542 542 79 71

SLBM 640 576 576 576 518

Bombers 76 68 68 22 18

All 1,258 1,186 1,186 677 607

Stephen J. Cimbala

102 S S Q ♦ F 2017

Table 4. Russia nuclear exchange outcomes (1,550 deployment limit)

(continued)

Type

Russia

New START 1,550 Balanced triad

DAY—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 542 542 542 542 488

SLBM 640 576 115 115 104

Bombers 76 68 0 0 0

All 1,258 1,186 657 657

591

DAY—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 542 542 542 54 49

SLBM 640 576 115 58 52

Bombers 76 68 0 0 0

All 1,258 1,186 657 112 101

Table 5. US nuclear exchange outcomes (1,000 deployment limit)

Type US New START 1,000 Balanced triad

GEN—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 300 300 300 300 270

SLBM 648 583 583 583 525

Bombers 48 43 43 43 35

All 996 926 926 926 830

GEN—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 300 300 300 30 27

SLBM 648 583 583 583 525

Bombers 48 43 43 14 11

All 996 926 926 627 563

DAY—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 300 300 300 300 270

SLBM 648 583 391 391 352

Bombers 48 43 0 0 0

All 996 926 691 691 622

DAY—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 300 300 300 30 27

SLBM 648 583 391 391 352

Bombers 48 43 0 0 0

All 996 926 691 421 379

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 103

Table 6. Russia nuclear exchange outcomes (1,000 deployment limit)

Type

Russia

New START 1,000 Balanced triad

GEN—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 342 342 342 342 308

SLBM 576 518 518 518 467

Bombers 76 68 68 68 55

All 994 928 928 928 830

GEN—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 342 342 342 59 53

SLBM 576 518 518 518 467

Bombers 76 68 68 22 18

All 994 928 928 599 538

DAY—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 342 342 342 342 308

SLBM 576 518 104 104 93

Bombers 76 68 0 0 0

All 994 928 446 446 401

DAY—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 342 342 342 34 31

SLBM 576 518 104 52 47

Bombers 76 68 0 0 0

All 994 928 446 86 78

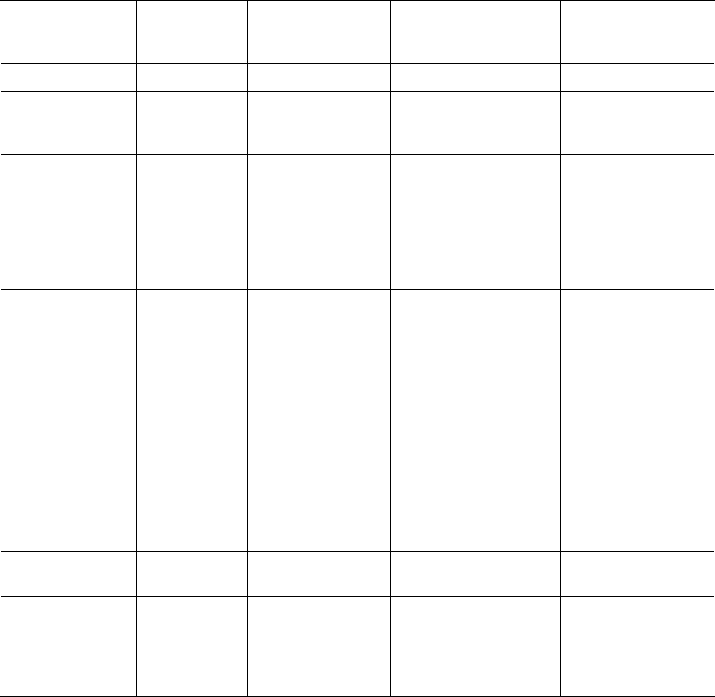

Table 7. US nuclear exchange outcomes (500 deployment limit)

Type US New START 500 Balanced triad

GEN—LOW

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 115 115 115 115 104

SLBM 336 302 302 302 272

Bombers 48 43 43 43 35

All 499 460 460 460 4 11

GEN—ROA

Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 115 115 115 12 10

SLBM 336 302 302 302 272

Bombers 48 43 43 14 11

All 499 460 460 328 293

Stephen J. Cimbala

104 S S Q ♦ F 2017

Table 7. US nuclear exchange outcomes (500 deployment limit) (continued)

Type US New START 500 Balanced triad

DAY—LOW Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 115 115 115 115 104

SLBM 336 302 203 203 182

Bombers 48 43 0 0 0

All 499 460 318 318 286

DAY—ROA Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 115 115 115 12 10

SLBM 336 302 203 203 182

Bombers 48 43 0 0 0

All 499 460 318 215 192

Table 8. Russia nuclear exchange outcomes (500 deployment limit)

Type Russia New START 500 Balanced triad

GEN—LOW Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 257 257 257 257 231

SLBM 192 173 173 173 156

Bombers 51 46 46 46 37

All 500 476 476 476 424

GEN—ROA Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 257 257 257 50 45

SLBM 192 173 173 173 156

Bombers 51 46 46 15 12

All 500 476 476 238 213

DAY—LOW Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 257 257 257 257 231

SLBM 192 173 35 35 31

Bombers 51 46 0 0 0

All 500 476 292 292 262

DAY—ROA Total Available Alert Surviving Arriving

ICBM 257 257 257 26 23

SLBM 192 173 35 17 16

Bombers 51 46 0 0 0

All 500 476 292 43 39

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 105

e preceding tables show that each state has numbers of surviving

and retaliating weapons sucient to satisfy the criterion of “unacceptable

damage” in a second strike so long as unacceptable damage is dened by

reference to the destruction of populations and societal values alone. If

we use McGeorge Bundy’s formula of 10 weapons on 10 cities as a

“disaster beyond history,” then even 500 deployed weapons provide

several hundred retaliatory warheads for either side under plausible

conditions of nuclear attack and response.

13

However, this “city busting”

criterion does not address the more nuanced requirements imposed

on US (and doubtless Russian) military planners. Essentially, policy

makers and planners have three paths or opportunities here: (1) drop the

numbers of deployed weapons and launchers to a “minimum deterrent”

standard, (2) agree to more limited nuclear reductions in a post–New

START regime (New START light), and/or (3) “multilateralize” the

arms-reduction talks to include China (essential if minimum deterrence

is the goal but still useful if larger than minimum deterrent forces are

being considered as the endgame).

What actually gets decided in Washington or in Moscow depends

as much on politics as it does on strategy. On one hand, it will be dif-

cult to sell domestic political forces in the United States (for example,

Republican members of Congress) or in Russia (the Russian military-

industrial complex) on post–New START reductions as drastic as a

maximum deployment limit of 500 weapons. In addition, such a truly

minimum deterrent option for the United States and Russia would

require that the post–New START negotiations be expanded to include

other nuclear weapons states. On the other hand, reductions to a maxi-

mum number of 1,000 operationally deployed weapons for each state

should be politically feasible. Russia’s nuclear force modernization plans

are ambitious but not necessarily aordable or otherwise feasible. e

current status of Russia’s military-industrial complex is less than enviable.

Russia’s nuclear warning and C3 system (command, control, and com-

munications) system has serious deciencies in satellite coverage and

other weaknesses.

14

It might turn out that Russia’s New START–compliant

force will level o at some number below 1,550 deployed warheads and

that Russia would be quite agreeable to the 1,000 benchmark for further

reductions. At the same time, if a post–New START regime follows

New START counting rules, each bomber would count as one weapon,

and the actual number of weapons deployed by each state would exceed

Stephen J. Cimbala

106 S S Q ♦ F 2017

the notional deployment ceiling (1,000) by several hundred warheads.

A US-Russian post–New START agreement for a maximum of 1,000

operationally deployed long-range weapons maintains their shared

“nuclear superpower” status relative to other nuclear weapons states and

should be considered one possibility for the nuclear posture review. is

status, however, confers responsibilities on Moscow and Washington for

taking the lead in reducing nuclear danger, including measures to pre-

vent the further spread of nuclear weapons and to roll back existing cases

of system-disturbing nuclear proliferation in states such as North Korea.

Missile Defenses: Prophecy or Problem?

Missile defenses, if successful, oer the possibility that deterrence

by threat of unacceptable retaliation could be supported by deterrence

based on denial of the attacker’s objectives.

15

Today missile defenses

remain technologically and politically contentious. Russian objections

to the US- and NATO-proposed European Phased Adaptive Approach

(EPAA) to missile defenses remained emphatic even as US Department

of Defense studies cast doubt on the technical prociency of the pro-

posed components for the European BMD (ballistic missile defense)

systems.

16

A study by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) on mis-

sile defense technologies called into question some of the thinking of

the Obama administration and the Missile Defense Agency about the

priority of certain missions and technologies for BMD.

17

But other expert

scientists criticized the NAS study as containing “numerous awed as-

sumptions, analytical oversights, and internal inconsistencies” leading

to “fundamental errors in many of the report’s most important ndings

and recommendations” and as undermining its scientic credibility.

18

Future technology challenges to the development and deployment of

missile defenses will have more to do with the complexity of software

engineering for multiple contingencies and players, compared to the

bipolar and physics-centric context of the Cold War.

19

Suce it to say

that the academic and policy arguments continue as to the feasibility

and desirability of building missile defenses, alongside the inertial pull

of research and development funding in this direction since the Reagan

administration’s Strategic Defense Initiative.

20

But this issue remains

important to the nuclear posture review.

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 107

If the linkage between US and NATO plans for European missile

defenses and further progress in US-Russian strategic nuclear arms

reductions was not yet a hostage relationship, it was clearly a problem-

atical connection.

21

e New START agreement does not preclude the

United States from deploying future missile defenses, despite Russian

eorts during the negotiating process to restrict American degrees of

freedom in this regard.

22

Former Russian president Dmitri Medvedev and

his predecessor-successor Vladimir Putin made it clear that Russia’s geo-

strategic perspective links US and NATO missile defenses to cooperation

on other arms control issues. Meanwhile, in 2011 the United States and

NATO moved forward with the rst phase of a four-phase deployment

of the EPAA for missile defenses.

23

In March 2013, secretary of defense

Chuck Hagel announced plans to modify the original plan for EPAA by

abandoning the originally planned deployments of SM-3 IIB interceptor

missiles in Poland by 2022. But this step failed to reassure Russian skeptics

about the claims that US and NATO regional and global missile defenses

were not oriented against Russia. Russian ocials frequently reiterate de-

mands for a legally binding guarantee from the United States and NATO

that Russian strategic nuclear forces would not be targeted or aected by

the system.

24

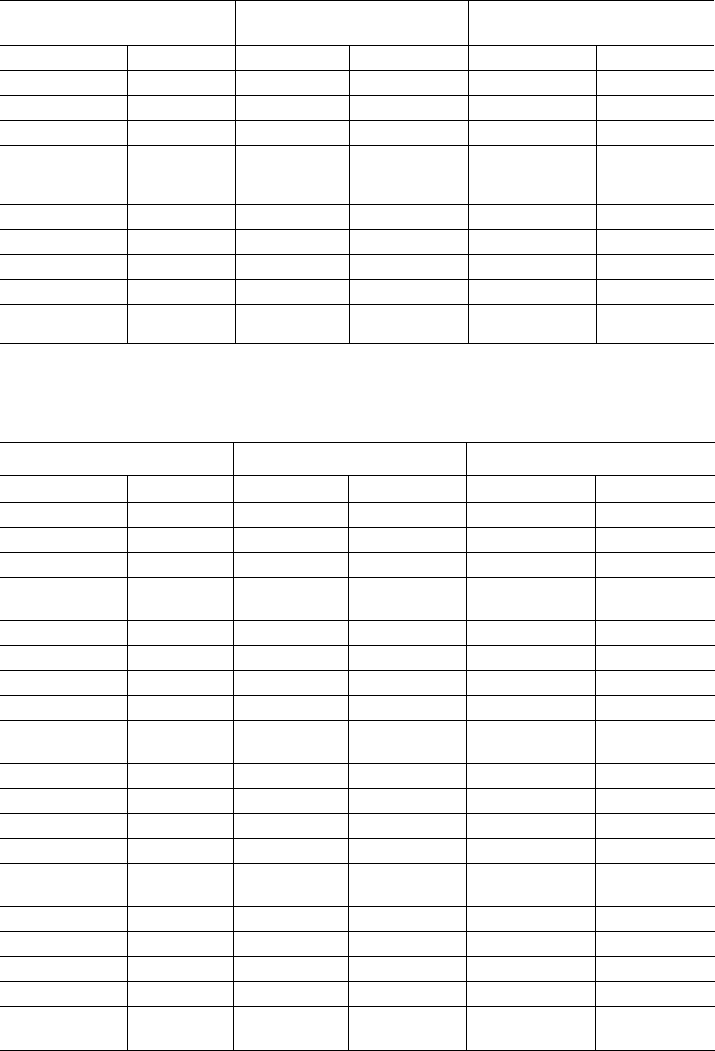

Table 9 summarizes the status of the EPAA BMD as of

autumn 2013.

Although the prospects for US-Russian or NATO-Russian agreement

on European missile defenses might seem challenging at this writing,

the prospects for American cooperation with allies and partners outside

of Europe on regional missile defenses are more favorable. e potential

bull market for missile defenses lies in Asia, including prompts from

Sino-Japanese rivalry, North Korean threats and missile tests, and de-

terrence challenges between India and Pakistan. Missile defenses might

appeal to states in Asia as support for deterrence by denial of enemy at-

tack and as a means of damage limitation, should deterrence fail. Missile

defenses for some US allies and partners might also reinforce security

guarantees based on the American nuclear umbrella and consequently

reduce the incentives for those states to develop their own nuclear arse-

nals.

25

Each of these BMD aspects have direct bearing on and relevance

to the US nuclear posture review.

Stephen J. Cimbala

108 S S Q ♦ F 2017

Table 9. European phased adaptive approach to missile defense

Facet Phase I Phase II Phase III

Phase IV

(canceled March

2013)

Time frame 2 011 2015 2018 2020

Capability Deploying

today’s

capability

Enhancing

medium-range

missile defense

Enhancing

intermediate-range

missile defense

Early intercept of

MRBM

a

, IRBM

b

,

and ICBM

c

Threat/mission Address

regional bal-

listic missile

threats to

Europe and

deployed US

personnel

Expand de-

fended area

against short-and

medium-range

missile threats to

Southern Europe

Counter short-,

medium-, and

intermediate-range

missile threats to

include all of Europe

Cope with MRBMs,

IRBMs, and

potential future

ICBM threats to the

United States

Components AN/TPY-2

(FBM)

d

in

Kurecik,

Turkey;

C2BMC

e

in

Ramstein,

Germany;

Aegis BMD

f

ships with

SM

g

-3 IA off

the coast of

Spain

AN/TPY-2 (FBM)

in Kurecik,

Turkey; C2BMC

in Ramstein,

Germany; Aegis

BMD ships with

SM-3 IB off the

coast of Spain;

Aegis Ashore

h

with SM-3 1B in

Romania

AN/TPY-2 (FBM) in

Kurecik, Turkey;

C2BMC in Ramstein,

Germany; Aegis BMD

ships with SM-3 IIA

off the

coast of Spain;

Aegis

Ashore

with SM-3 IB/IIA in

Romania and Poland

AN/TPY-2 (FBM) in

Kurecik, Turkey;

C2BMC in

Ramstein, Ger-

many; Aegis BMD

ships with SM-3 IIA

off the

coast of Spain;

Aegis

Ashore

with SM-3 IIB

in Romania and

Poland

Technology Exists In testing Under development In conceptual stage

when canceled

Locations Turkey,

Germany,

ships off

the coast of

Spain

Turkey,

Germany, ships

off the coast of

Spain, ashore in

Romania

Turkey, Germany,

ships off the coast

of Spain, ashore in

Romania and Poland

Turkey, Germany,

ships off the coast

of Spain, ashore

in Romania and

Poland

Note: Separate national contributions to the mission of European BMD have been announced by Netherlands and France.

Source: Karen Kaya, “NATO Missile Defense and the View from the Front Line,” Joint Force Quarterly 71 (4th Quarter 2013): 86,

http://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ/Joint-Force-Quarterly-71/.

a

Medium-range ballistic missile

b

Intermediate-range ballistic missile

c

Intercontinental ballistic missile

d

AN/TPY-2 (FBM)—Army Navy/Transportable Radar Surveillance, Model 2 (Forward-based Mode)

e

Command, control, battle management, and communications

f

Ballistic missile defense

g

Standard missile

h

Land-based component of the Aegis BMD system

Beyond the Nuclear Posture Review per se, the question of missile

defenses raises important issues having to do with the relationship be-

tween the politics and the technology of deterrence. Missile defenses

that are “too good” potentially undermine stable deterrence based on

assured retaliation that inicts unacceptable damage. But a mixture of

defenses of uncertain performance with oenses threatens to create an

open-ended arms race and additional uncertainties that, during a crisis,

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 109

might contribute to rst-strike fears. Added to this, new technologies

for improved accuracy in long-range strike weapons and better remote

sensing could pose greater threats to platform survivability based on

hardening or concealment. And, once having been deployed, defenses

would themselves become attractive targets for defense-suppression at-

tacks, creating incentives for pre-preemptive strikes against defenses

while preemption against enemy oensive forces remained on the table.

To be clear, the next NPR will have to address how oenses and defenses

work together to (1) support deterrence and defense policy objectives

and (2) remember the lessons learned from years of Cold War and later

experience about the unique character of nuclear weapons and nuclear

danger, albeit in a changing world.

Conclusions and Recommendations

e United States and Russia have opportunities for nuclear arms

reductions if other issues of military-strategic disagreement, including

Russia’s possible violation of the INF Treaty, can be managed success-

fully. However, arms control is primarily a political process, not a tech-

nical one. e two states must agree that their leadership on global non-

proliferation and nuclear risk reduction is a matter of priority on account

of their large arsenals, their high visibility in nuclear world politics, and

their experience in nuclear consultation and negotiation. Analysis shows

that US-Russian strategic nuclear stability is possible at various levels of

deployed warheads and launchers. e Trump administration’s nuclear

posture review might be just the occasion for new ideas, including new

departures in nuclear arms control. Several possibilities and recommen-

dations emerge.

1. e United States and Russia should agree now to extend the

duration of the New START treaty and, in addition, enter into

discussions about post–New START reductions consistent with

strategic stability.

2. Military-to-military exchanges between US and Russian special-

ists, suspended during the Obama administration, should be re-

sumed in the interest of transparency and security.

3. US-Russian arms-reduction talks should deal not only with simple

counts and verication but also with the larger contexts of strategy

Stephen J. Cimbala

110 S S Q ♦ F 2017

and security as perceived by both states; for example, what are the

consequences of possible improvements in missile defenses and in

conventional long-range precision strike weapons, for nuclear de-

terrence based on assured retaliation?

4. Since the likelihood of a tactical nuclear rst use is higher than

the probability of a separate decision for a strategic nuclear rst

strike, more transparency about NATO and Russian tactical nu-

clear weapons deployed in Europe and in Asia is essential. An out-

break of accidental or inadvertent nuclear war growing of out of an

escalation from conventional war is as likely, or more likely, than

a mistaken strategic nuclear response per se. At the same time,

smaller weapons are, for deterrence purposes, ambiguously con-

nected to the possible employment of larger and more destructive

forces. Tactical nuclear weapons are linked to strategic weapons

because of the complex dual nature of the former: they are possible

rebreaks between lesser and greater degrees of war. e process of

negotiating increased transparency with respect to the numbers,

locations, and capabilities of tactical nukes should begin now.

26

But the road to tactical nuclear arms reductions as between NATO

and Russia is a much more dicult problem than further reduc-

tions in US and Russian strategic nuclear weapons, and for that

reason it requires a separate study in its own right.

5. US-Russian cooperation on theater missile defenses in Europe

should be encouraged, including the development of joint cent-

ers of observation and monitoring against threats from the Mid-

dle East or other outside-of-Europe locations. Current generations

of strategic antimissile defenses are promissory notes, not proven

technologies under conditions of wartime stress.

27

Russian o-

cials continue to assert nevertheless that current and prospective

US missile defense plans threaten the viability of Russia’s nuclear

deterrent and, therefore, international stability.

28

Doubtless future

antimissile technologies will improve relative to ballistic oensive

weapons, given the ages of the latter.

29

However, the ultimate out-

come of competition between defensive antimissiles and oensive

countermeasures remains at the mercy of creative science and en-

gineering as well as politics and state priorities.

30

US- and NATO-

proposed missile defenses for Europe are admittedly a matter of

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 111

contemporary controversy.

31

But they should not be an excuse for

Russia, the United States, or NATO to defer progress on strategic

and nonstrategic nuclear reductions in oensive weapons.

Many of these recommendations might be grouped under the head-

ing of creating new, or revived, knowledge communities among arms-

control specialists and others in the national security and military studies

worlds. ese communities would cut across professional and national

boundaries to bring together interested specialists and policy makers for

discussions about their perspectives on nuclear deterrence, crisis man-

agement, nonproliferation, nuclear security, and other issues. Some-

thing like this occurred between the United States and the Soviet Union

during the Cold War. Over time, shared expectations and understand-

ings about the bases of nuclear deterrence, the “deliverables” possible in

arms control, and the challenges of nuclear crisis management helped to

control the arms race and bring a peaceful end to the Cold War. In the

twenty-rst century, academics and practitioners will have to shepherd

understandings about the relationship between oenses and defenses,

the implications of cyberwar for nuclear deterrence, and the impact of

third oset technologies (articial intelligence, nanotechnology, and

3-D manufacturing, among others) on nuclear arms control and deter-

rence strategy. In addition, the conversation on strategic nuclear arms

control must move from a two-sided American and Russian experience

toward a tripartite nuclear summitry that includes China, despite indi-

vidual, dierent policy objectives, experiences, and strategic perspectives

with respect to nuclear weapons.

With regard to arms control more generally, Paul Bracken emphasizes

that the challenges of the second nuclear age may be very dierent from

the rst: “Arms control is in desperate need of fresh ideas. It’s like Sanka,

an old, tired brand that is still around but in need of a makeover. I want

to put the challenge to arms control in just this way. Without new en-

ergy and a new edginess, arms control’s downward spiral into irrelevance

will continue. Arms control is too important to allow this to happen.”

32

e nuclear posture review presents an opportunity for fresh ideas

and new energy to prevent the collapse and relevance of arms control.

e Trump administration and the Department of Defense should seize

this opportunity before it fades away.

Stephen J. Cimbala

112 S S Q ♦ F 2017

Notes

1. For example, see Peter Baker, Neil MacFarquhar, and Michael R. Gordon, “Syria Strike

Puts U.S. Relationship with Russia at Risk,” New York Times, 7 April 2017, https://www

.nytimes.com/2017/04/07/world/middleeast/missile-strike-syria-russia.html.

2. Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures

for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Oensive Arms (Washington, DC: De-

partment of State, 8 April 2010), http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/140035.pdf.

3. Aaron Mehta, “Former SecDef Perry: US on ‘Brink’ of New Nuclear Arms Race,” De-

fense News, 3 December 2015, http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/policy-budget

/2015/12/03/former-secdef-perry-us-brink-new-nuclear-arms-race/76721640/.

4. Philip M. Breedlove, “NATO’s Next Act: How to Handle Russia and Other reats,”

Foreign Aairs, July/August 2016, https://www.foreignaairs.com/articles/europe/2016-06-13

/natos-next-act. On current and prospective Russian strategic military thinking, see Stephen

R. Covington, e Culture of Strategic ought behind Russia’s Modern Approaches to Warfare

(Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School, October 2016).

5. BBC, “Russia Security Paper Designates NATO as reat,” 31 December 2015, http://

www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35208636.

6. See, for example, Mark B. Schneider, Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and

Security Review Commission, Hearing on “Developments in China’s Cyber and Nuclear Ca-

pabilities,” 26 March 2012, http://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/les/3.26.12schneider.pdf; and

Oce of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress, Military and Security Develop-

ments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2014 (Washington, DC: Oce of the Secretary

of Defense, 2014), https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2014_DoD_China

_Report.pdf.

7. For example, see Ariel Cohen and Robert E. Hamilton, e Russian Military and the

Georgian War: Lessons and Implications (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army

War College, June 2011); and Rod ornton, Military Modernization and the Russian Ground

Forces (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College, June 2011).

8. Timothy L. omas, Russia: Military Strategy: Impacting 21st Century Reform and Geo-

politics (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Oce, 2015), 253–99. omas dis-

cusses Russian concepts of information warfare and related policy and planning decisions.

9. For an expert appraisal of Russian military thinking about tactical nuclear weapons,

see Jacob W. Kipp, “Russian Doctrine on Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Contexts, Prisms, and

Connections,” in Tactical Nuclear Weapons and NATO, ed. Tom Nichols, Douglas Stuart,

and Jerey D. McCausland (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, April 2012), 116–54.

See also Olga Oliker, “No, Russia Isn’t Trying to Make Nuclear War Easier,” National Interest,

23 May 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/no-russia-isnt-trying-make-nuclear-war

-easier-16310.

10. Regardless the outcome of the analysis, the exercise is necessary in order to impose

analytical boundaries on the discussion. See Keith B. Payne, “Why US Nuclear Force Numbers

Matter,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 10, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 14–24, http://www.au.af.mil

/au/ssq/digital/pdf/Summer16/Payne.pdf.

11. Grateful acknowledgment is made to James Scouras for use of his Arriving Weapons

Sensitivity Model in this study. Dr. Scouras is not responsible for its use here or for any argu-

ments in this paper.

12. Force structures in the analysis are notional and not necessarily predictive of actual

deployments. For expert appraisal, see, in addition to previous citations, Hans M. Kristensen,

“Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear

Forces,” Special Report no. 5 (Washington, DC: Federation of American Scientists, December

Nuclear Arms Control

S S Q ♦ F 2017 113

2012), https://fas.org/pub-reports/trimming-nuclear-excess/; Gen James Cartwright, retired,

chair, Global Zero Nuclear Policy Commission, Report: Modernizing U.S. Nuclear Strategy,

Force Structure and Posture (Washington, DC: Global Zero, May 2012), https://www.globalzero

.org/les/gz_us_nuclear_policy_commission_report.pdf; and Pavel Podvig, “New START

Treaty in Numbers,” Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces (blog), 9 April 2010, http://russianforces

.org/blog/2010/03/new_start_treaty_in_numbers.shtml. See also Joseph Cirincione, “Strategic

Turn: New U.S. and Russian Views on Nuclear Weapons,” New America Foundation, 29 June

2011, http://newamerica.net/publications/policy/strategic_turn; and Arms Control Associa-

tion, “U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces under New START,” http://www.armscontrol.org/fact

sheets/USStratNukeForceNewSTART.

13. McGeorge Bundy, “To Cap the Volcano,” Foreign Aairs 48, no. 1 (October 1969):

10, http://doi.org/d6mc7p.

14. Russia’s strategic nuclear forces and their progression may be followed on Pavel Podvig’s

expert blog, Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. See, for example, “New START Treaty in Numbers,”

n. 12.

15. According to Adam B. Lowther, deterrence can be conceptualized as a continuous

spectrum with three components: deterrence by dissuasion, deterrence by denial, and deter-

rence by threat. Moving across the spectrum from dissuasion through denial to threat in-

creases the level of action by the state attempting to deter. See Lowther, “How Can the United

States Deter Nonstate Actors?” in Deterrence: Rising Powers, Rogue Regimes, and Terrorism in

the Twenty-rst Century, ed. Adam Lowther (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2012), 163–82,

esp. 166–67.

16. Desmond Butler, Associated Press, “Flaws Found in U.S. Missile Shield for Europe,”

Army Times, 9 February 2013, http://www.armytimes.com/mobile/news/2013/02/ap-aws

-missile-shield-020913. See also “U.S. Missile Defense Shield Flawed: Classied Studies,” Russia

Today, 9 February 2013, https://www.rt.com/usa/us-missile-defense-aws-811/.

17. Committee on an Assessment of Concepts and Systems for U.S. Boost-Phase Missile

Defense in Comparison to Other Alternatives, Making Sense of Ballistic Missile Defense (Wash-

ington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, National Academies

Press, 2012), https://www.nap.edu/read/13189/chapter/1.

18. George N. Lewis and eodore A. Postol, “e Astonishing National Academy of

Sciences Missile Defense Report,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 20 September 2012, http://

thebulletin.org/astonishing-national-academy-sciences-missile-defense-report.

19. Rebecca Slayton, Arguments that Count: Physics, Computing, and Missile Defense,

1949–2012 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 188–97.

20. Superior treatment of technical, political, and economic challenges to US and NATO

plans for European missile defenses is provided in Steven J. Whitmore and John R. Deni,

NATO Missile Defense and the European Phased Adaptive Approach: e Implications of Burden

Sharing and the Underappreciated Role of the U.S. Army (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College,

October 2013).

21. For US and NATO missile defense plans, see LTG Patrick J. O’Reilly, USA, director,

Missile Defense Agency, “Ballistic Missile Defense Overview” (presentation, 10th Annual

Missile Defense Conference, Washington, DC, 26 March 2012, https://mostlymissiledefense

.les.wordpress.com/2013/06/bmd-update-oreilly-march-2012.pdf.

22. Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation.

23. See Karen Kaya, “NATO Missile Defense and the View from the Front Line,” Joint

Force Quarterly 71 (4th Quarter 2013): 84–89, http://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ/Joint-Force

-Quarterly-71/; John F. Morton and George Galdorisi, “Any Sensor, Any Shooter: Toward an

Aegis BMD Global Enterprise,” Joint Force Quarterly 67 (4th Quarter 2012): 85–90, http://

Stephen J. Cimbala

114 S S Q ♦ F 2017

ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-67/JFQ-67_85-90_Morton-Galdorisi.pdf;

and Frank A. Rose, deputy assistant secretary, Bureau of Arms Control, Verication and Com-

pliance, “Growing Global Cooperation on Ballistic Missile Defense, Remarks as Prepared,

Berlin, Germany,” 10 September 2012, http://www.state.gov/t/avc/rls/197547.htm.

24. For example, see RIA Novosti, “Moscow Needs More ‘Predictability’ in NATO Missile

Defense Plans,” Sputnik News, 23 October 2013, https://sptnkne.ws/eHdh.

25. See Kevin Ayers, “Expanding Zeus’s Shield: A New Approach for eater Ballistic

Missile Defense in the Asia-Pacic Region,” Joint Force Quarterly 84 (1st Quarter 2017):

24–31, http://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-84/jfq-84_24-31_Ayers.pdf,

for a discussion of challenges and opportunities. See also essays in e Asia-Pacic Century:

Challenges and Opportunities, ed. Adam Lowther (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University

Press, April 2013).

26. Pavel Podvig, “What to Do about Tactical Nuclear Weapons,” Bulletin of the Atomic

Scientists, 25 February 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20100504022115/http://www

.thebulletin.org:80/web-edition/columnists/pavel-podvig/what-to-do-about-tactical-nuclear

-weapons.

27. Slayton, Arguments that Count, 199–226. Slayton oers pertinent historical perspective.

See also Keir Giles with Andrew Monaghan, European Missile Defense and Russia (Carlisle, PA:

Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College Press, July 2014); and Andrew Futter, Bal-

listic Missile Defence and US National Security Policy: Normalization and Acceptance after the

Cold War (New York: Routledge, 2013).

28. For example, at the Geneva disarmament conference in March 2017, Lieutenant

General Viktor Poznikhir, deputy head of the Main Operations Department of the Russian

General Sta, averred that deployment of US missile defenses “ruins the current system of

international security” and that “the United States hopes to gain strategic advantage by down-

grading the deterrence potentials of Russia and China. is may cause serious eects in the

eld of security.” Poznikhir, cited in “Military Expert Warns US ABMs Can Detect Any

Missile Shield, Even Russian Ones,” TASS, 28 March 2017, http://tass.com/defense/937949.

29. For example, the possibility of “left-of-launch” techniques for interfering with enemy

missile launches before missiles actually reach the launch pad or during the launch itself. See

David E. Sanger and William J. Broad, “Trump Inherits a Secret Cyberwar against North

Korean Missiles,” New York Times, 4 March 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/04/...

/north-korea-missile-program-sabotage.html.

30. Morton and Galdorisi, “Any Sensor, Any Shooter.”

31. For US and NATO missile defense plans under the European phased adaptive approach,

see Kaya, “NATO Missile Defense,” and O’Reilly, “Ballistic Missile Defense Overview.”

32. Paul Bracken, e Second Nuclear Age: Strategy, Danger, and the New Power Politics

(New York: Henry Holt–Times Books, 2012), 260–61. For an illustration of some new ap-

proaches, see the collaborative work between RAND and the Korea Institute for Defense

Analyses in Paul K. Davis, Peter Wilson, Jeongeun Kim, and Junho Park, “Deterrence and

Stability for the Korean Peninsula,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 23, no. 1 (Spring 2016):

1–23, http://www.kida.re.kr.

Disclaimer

e views and opinions expressed or implied in SSQ are those of the

authors and are not ocially sanctioned by any agency or depart-

ment of the US government. We encourage you to send comments

to: [email protected].