A GUIDE TO VIRGINIA RESIDENTIAL

LANDLORD & TENANT LAW

Bryan Grimes Creasy

Johnson, Ayers & Matthews, P.L.C.

310 First Street – Suite 700

Roanoke, Virginia 24011

Phone: (540) 767-2000

Fax: (540) 982-1552

UNLAWFUL DETAINER ACTIONS UNDER VIRGINIA LAW

Landlords are in the business of maximizing the total number of occupants within

a property’s available living space. A high occupancy rate equates to a high cash inflow.

Therefore, in general, eviction is not a welcome procedure as the eviction of a tenant

results in a vacancy and a loss of expected revenue. Nonetheless, when a tenant is

unwilling or unable to abide by the terms of a lease agreement, the tenant must be

removed quickly and efficiently. Non-paying and problem tenants make property

management difficult and frustrating. A protracted eviction process will result in lost

potential revenue and lost opportunity costs. In those situations, a clean and quick

eviction process is an important and helpful tool for landlords. During the course of an

eviction, issues of outstanding rent, late fees, damages, and attorneys’ fees will be sought

and disputed by the respective parties. This outline will review how these issues are

addressed under applicable Virginia law.

Please note that there are exceptions as to what properties are covered by the

Virginia Residential Landlord and Tenant Act (“VRLTA”).

1

However, with the

reduction of the trigger number under Virginia Code Section 55-248.3:1(B), the majority

of residential leases will now be covered by the VRLTA. Further, in recent legislative

sessions, the General Assembly has begun placing multiple sections of the VRLTA into

the Landlord and Tenant Act

2

, which has significantly reduced the differences between

the two Acts. Therefore, this outline will focus primarily on the eviction process for

VRLTA properties. Although there are still remaining differences between the VRLTA

and the Landlord and Tenant Act, the VRLTA is more comprehensive and more often

relied upon and referred to in unlawful detainer actions than the Landlord and Tenant

Act. Thus, the VRLTA will be the main focus and subject of this outline and CLE

course. Differences between the two Acts will be noted along each step of the guide.

STEP ONE - Identify a Breach of the Lease

Property managers and landlords often articulate problems created by tenants, but

they routinely fail to link the tenant’s behavior with a particular lease provision or

applicable statute. Property managers and landlords must be instructed to identify the

1

Virginia Code Sections 55-248.2 through 55-248.40.

2

Virginia Code Sections 55-217 through 55-248.

Page 2 of 24

precise nature of the breach, and they have to be instructed to detail the underlying breach

in the subject notice.

The following are common examples of instances whereby a tenant breaches a

lease agreement or statutory provision:

Example 1: Failure to pay rent

o Although one would assume that landlords quickly address tenants who

fail to pay monthly rent; however, landlords regularly fail to address this

issue quickly. Landlord’s often accept a partial payment and hope that the

tenant’s next payment will be for the full amount owed. Once a tenant

starts to fall behind, non-payment usually follows, which becomes

compounded with the imposition of late fees. Thus, landlords should

adhere to a consistent policy of sending notices unless they receive the full

rent amount.

Example 2: Breach of quiet enjoyment

o Well written leases contain a provision requiring that a tenant respect the

quiet enjoyment of the leased premises and common areas. Situations

often arise whereby tenants cause disturbances disrupting other tenants.

Practitioners should encourage their landlord/property manager clients to

document any such incidents. Thorough documentation will make success

during the trial phase more likely. Landlords should send 21/30 material

non-compliance notices following such a breach. The number of 21/30

notices to be sent prior to filling a Summons for Unlawful Detainer is

usually dictated by the severity of the breach.

Example 3: Failure to abide by occupancy restrictions

o Most leases require the prospect to list individuals, who will be living on

the premises. Many leases also require that only those individuals listed in

the lease reside on the premises. On occasion, tenants will permit

unauthorized friends and family to move into the leased premises. These

situations are difficult for property managers and landlords to detect and to

prove. Mail carriers may report to the staff when a given residence

receives large amounts of mail to an unauthorized person within the leased

premises. Property managers should also look for unregistered vehicles

parked in the housing community lot.

Example 4: Failure to maintain utilities and services

o Tenants generally maintain the utilities as a necessity for sustainable

living. In some cases, tenants may fail to maintain the proper utilities.

Landlords and property managers should move quickly against such

Page 3 of 24

tenants to avoid property damage, especially in extreme weather

conditions.

Questions:

1) Can a landlord change the locks on the apartment and lock the tenant out

following a breach of the lease?

Absolutely not. Virginia Code Sections 55-225.1 and 55-248.36 expressly

prohibit the landlord from recovering possession except by lawful and permitted

means. Consequently, Virginia law no longer recognizes the right of “self-help”

in residential landlord and tenant situations. Self-help remedies are still available

in non-residential tenancies. (See Va. Code § 55-225)

2) Can a landlord dispose of the tenant’s furniture following a breach of the

lease and/or apparent abandonment?

Items of personal property left in the leased premises at the end of the tenancy are

to be treated as abandoned property, which will require the landlord to comply

with Virginia Code Section 55-248.38:1. In such a scenario, prior to disposing of

any abandoned property, including furniture, the landlord must provide the former

resident with the appropriate notice as set forth under the aforementioned code

section. If possession was obtained by lawful Court order and by way of a writ of

eviction, then the personal property may be disposed of in accordance with

Virginia Code Section 55-248.38:2. Also please refer to Step Nine for additional

information.

STEP TWO - Serve the Proper Notice

Under the VRLTA, notices are an integral part of a good landlord-tenant practice.

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.6, the VRLTA deems notice of a fact when a

person:

o has actual knowledge of a fact, or

o has received verbal notice of the fact, or

o has reason to know that such a fact exists.

The VRLTA defines “Notice” as one:

o given in writing by either regular mail or hand delivery, with the sender

retaining sufficient proof of having given such notice, which may be either

a United States postal certificate of mailing or a certificate of service

confirming such mailing prepared by sender; or

o if the rental agreement so provides, notice may be sent in electronic form.

(See Virginia Code Section 55-248.6(B))

Page 4 of 24

Notice is served on the landlord at his place of business where the lease

agreement was made or at any place the landlord represents to be a place for receipt of

communication. Notice is served on the tenant at his last known place of residence,

which may be the dwelling unit. Notice received by an organization is effective for a

particular transaction at the time it is brought to the attention of the person conducting the

transaction, or from the time it would have been brought to his attention if the

organization had exercised reasonable diligence.

No notice to quit or notice of termination of tenancy served on a public housing

tenant is effective unless it contains on the first page, the name, address, and telephone

number of the legal services program, if any, serving the jurisdiction in which the rental

premises are located.

Notices must set forth the proper time periods permitting the tenant an

opportunity to remedy his breach or a statutory time period within which to surrender

possession of the premises, as required by the VRLTA. If the property is governed by

HUD such as a Section 8 based property, the notices must also strictly comply with the

applicable HUD regulations and guidelines.

Examples:

Example 1: 21/30 Material Non-Compliance Notice

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.31, a 21/30 material non-compliance

notice should be sent to tenants when they breach the lease in such a way that the breach

could be remedied and cured.

3

For example, assume a hypothetical situation whereby neighbors complain about

a particular tenant’s loud and disturbing behavior, to which the landlord may send this

notice to indicate that the tenant has 21 days within which to remedy his breach of the

lease for his failure to comply with the lease’s quiet enjoyment provision. Should the

landlord receive any further verifiable complaints within 21 days, the tenant must vacate

the premises within 30 days from the date of the notice. On the other hand, if the tenant

does not violate the quiet enjoyment provision, then he may remain on the premises

through the duration of the lease term, provided there are no other breaches of the lease.

Example 2: Material Non-Compliance for Failure to Pay Rent

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.31, this notice should be used when a

tenant fails to pay rent. This notice provides the tenant with an additional five days

within which to pay rent. Should the tenant fail to make payment for the amount due and

owing (including late fees), the owner may proceed with a Court proceeding to obtain a

money judgment, possession, and attorneys’ fees and costs, if applicable.

4

3

See a sample 21/30 Material Non-Compliance Notice attached as Appendix 1.

4

See a sample Material Non-Compliance Notice for Failure to Pay Rent attached as Appendix 2.

Page 5 of 24

Example 3: Notice of Termination – Non-Remediable Violation

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.31(C), this notice should be used in

situations whereby the tenant breaches the lease in such a way that there is no remedy.

This notice results in termination of the lease agreement. The tenant is permitted to

remain on the property for no less than 30 days upon receipt of this notice. This notice is

often utilized when the tenant takes part in criminal or illegal drug activity.

5

If the non-

remediable breach constitutes a criminal or willful act, which is not remediable and

which poses a threat to health or safety, the landlord may give the tenant an immediate

non-remediable breach of lease notice; commonly referred to as a 72 hour notice.

Example 4: Notice of Termination – Repeat Violation

This notice should be served on tenants when the subject breach of the lease

agreement is repeated in a similar or serial manner. For example, when a tenant violates a

quiet enjoyment provision of a lease, the owners may send a 21/30 notice. Then the

tenant may remedy the breach by not causing disruptions within the 21-day period. If, at

some point afterward the tenant violates the quiet enjoyment provision of the lease

agreement again, then this notice should be sent to the tenant to inform him of his

repeated violation. The notice requests possession of the premises within a period no less

than 30 days from the date of the notice.

6

Questions:

1) What actions should a landlord’s attorney take when the landlord has served

the wrong notice and there is a pending unlawful detainer return date?

To properly posture a landlord’s unlawful detainer action, the landlord must have

served the tenant with the appropriate notice in accordance with Virginia Code

Section 55-248.31. In the event the landlord served an incorrect notice, then the

defendant is afforded an opportunity to have the case dismissed based on that

error. Consequently, the landlord will be faced with one of two options. First,

nonsuit the pending unlawful detainer action, properly serve the correct notice,

and then re-file the unlawful detainer action. In the alternative, the case can be

continued to a date far enough in advance to allow the landlord to serve the proper

notice and to allow for that notice period to expire before then proceeding with

setting the unlawful detainer action for a trial on the merits. The one problem

with the second option is that you technically have a case pending prior to and

during the time that the termination notice is pending, which procedurally is not

the proper sequence. Thus, a nonsuit of the pending action would appear to be

more appropriate.

5

See a sample Notice of Termination – Non-Remediable Violation attached as Appendix 3.

6

See a sample Notice of Termination – Repeat Violation Notice attached as Appendix 4.

Page 6 of 24

STEP THREE - Identify and Compile the Proper Documentation

In preparation for the return date, the attorney should procure the following:

o a copy of the lease agreement;

o the relevant notice served following the breach and the attempted eviction,

o a copy of the account ledger indicating the amounts outstanding, if any;

o acceptance of rent with reservation notices, and if necessary an abstract of

a prior summons for unlawful detainer action that was dismissed per the

one right of redemption, (See Virginia Code Section 55-248.34:1); and

o affidavit per Virginia Code Section 8.01-126 - (See Step Six for further

discussion).

If the notices served on the tenant by the landlord or property manager are not the

proper notices, then the plaintiff’s case is defective. The attorney should request a

nonsuit to allow time for his client to correct the problems and to serve the proper notice.

After the landlord or property manager serves the proper notice and after the termination

period expires, the plaintiff’s attorney should re-file the unlawful detainer action using

the proper notice as its base. By taking these steps, the plaintiff’s case will be properly

positioned prior to the trial. (See also Question 1 in Step Two)

Depending on the jurisdiction, some General District Court judges prefer to hear

the contested matter at the time of the return date, instead of setting the matter for a

contested date. In those jurisdictions, it is necessary to prepare all the proper

documentation needed to participate in the contested hearing at that time instead of on a

separate and later court date, which will include securing the necessary witnesses to be

present at the return date.

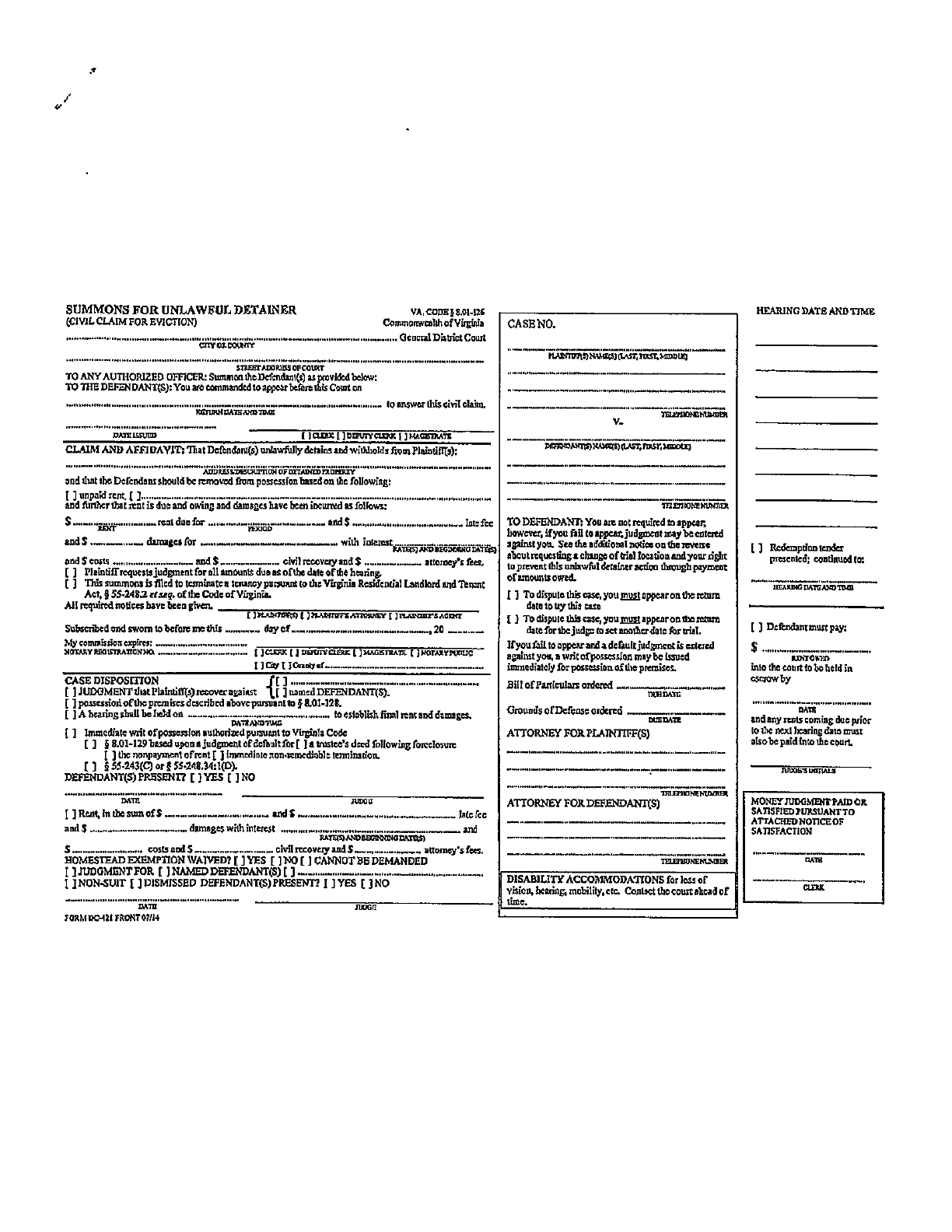

STEP FOUR - File the Unlawful Detainer

An unlawful detainer is filed pursuant to Virginia Code Sections 8.01-124 and

8.01-126.

7

The forms are available on the Virginia Judicial System website.

8

The proper

pleading for an eviction is an unlawful detainer and NOT a warrant in debt.

The pleading must indicate the basis for filing the unlawful detainer action. If the

basis for the unlawful detainer action is unpaid rent, then list all amounts due and owing,

including, but not limited to, rent, past due rent charges, fees, and attorneys’ fees. Note:

The form was updated in July 2014 and now includes a box for “Plaintiff requests

judgment for all amounts due as of the date of the hearing.” You will want to always

check that box as it will allow you to amend the amount of rent and other damages you

may be seeking without necessarily filing a motion for leave to amend. (See Virginia

Code Section 8.01-126 (C)(2)).

7

See a sample Unlawful Detainer attached as Appendix 5.

8

www.courts.state.va.us

Page 7 of 24

If the basis for the unlawful detainer is a breach of the lease, then indicate how the

lease was breached.

The plaintiff’s attorney must affirm that the proper notices have been properly

served on the tenants. The following information must be included on the unlawful

detainer:

Proper jurisdiction – the location of the leased premises;

The address of the leased premises;

Proper party names;

Rent, past due rent, and fees allegedly owed by defendant to plaintiff; and

If the lease or the VRLTA provides for attorneys’ fees, then indicate it on the

unlawful detainer.

Questions:

1) Should a landlord file an unlawful detainer action when it appears that the

resident has abandoned the property?

If the landlord can establish that the resident has abandoned the property and has

surrendered possession of it per Virginia Code Section 55-248.33, which may require the

service of a seven (7) day abandonment notice, then the landlord does not need to file an

unlawful detainer action because possession has already been re-established by the

landlord. On the other hand, if the landlord is unable to determine whether or not the

property has been abandoned and thus whether or not possession has been surrendered,

then the landlord should file an unlawful detainer action and allow for the Court to

determine who has the right of possession.

2) Does a landlord have to wait for the termination period to expire before

filing an unlawful detainer?

Yes. Once the landlord serves the appropriate termination notice as set forth under

Virginia Code Section 55-248.31, then the landlord must wait until that termination

period expires before the landlord proceeds with an unlawful detainer action. The

resident is not unlawfully detaining the unit while the notice remains in effect. Once the

notice expires and the resident has refused to vacate and to surrender possession of the

leased premises, then the landlord may argue and allege that the resident is unlawfully

detaining the unit, which will permit the landlord to proceed with the filing of a summons

for unlawful detainer seeking possession of the leased premises.

STEP FIVE - Prepare for Common Evidentiary Issues

Landlord and Tenant law is similar to other areas of contract law as the plaintiff

must show the existence of a contract, a breach, and the damages proximately caused by

the breach. The lease serves as proof of a contract with consideration. The ledger sheet

establishes the monetary damages. Both of these elements are usually proven through the

Page 8 of 24

property manager, who should, during the course of his or her testimony, identify and

introduce into evidence a copy of the lease, the account ledger, and the appropriate

notice(s). The property manager should also be able to testify regarding the authenticity

of both documents. Most of the testimony during a landlord and tenant case revolves

around establishing the breach.

The plaintiff must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the breach

referred to and identified in the notice is identical to the breach referred to on the face of

the unlawful detainer summons. The notice and the unlawful detainer summons should

list the same breach. Courts often strike evidence regarding the tenant’s alleged behavior

that plaintiff failed to include in the notice or in the unlawful detainer summons.

Prior to any Court appearance, the plaintiff’s attorney should identify all potential

evidence necessary to prove the tenant’s breach of the lease. It is straightforward and

easy to determine that the lease was breached for failure to pay rent on time. It can be

more difficult to prove other breaches. To prove other types of breaches, it may be

necessary to call witnesses, who observed or documented the breach. The property

manager, neighbors, police and/or security guards often provide helpful testimony

regarding the tenant’s activity, which resulted in the breach of the lease agreement.

Due to the statutory requirements, it is necessary to introduce the notice into

evidence and to prove that the notice was served properly, as required by Virginia Code

Section 55-248.6, and that the notice was proper and addressed the specific breach that

occurred in the case at bar in accordance with Section 55-248.31.

Questions:

1) How much can a landlord deduct from the tenant’s security deposit for a

carpet ruined by the tenant’s pet?

Virginia Code Section 55-248.15:1, subparagraph A, will permit the landlord to

make a deduction from the security deposit based on damages above reasonable

wear and tear suffered as a result of the resident’s noncompliance with Virginia

Code Section 55-248.16. Therefore, if the carpet has been ruined by pet urine,

excess traffic, or other such damage above reasonable wear and tear, the damage

charges can be deducted from the security deposit. If the damage to the carpet

can be repaired without replacement, then the landlord may deduct its actual costs

incurred in making the repair. On the other hand, if the carpet has been ruined to

the extent that it must be replaced, then the landlord may not deduct the actual

replacement cost of the carpet. Rather, the landlord may only deduct from the

security deposit the depreciated value of the carpet at the time of destruction.

(Please also note that, as of January 1, 2015, the statutory requirement to accrue

interest on security deposits was repealed.)

Page 9 of 24

STEP SIX - Prepare for and Attend the Return Date

Many unlawful detainers result in default judgments, particularly in cases brought

for non-payment of rent. Nevertheless, the plaintiff’s attorney must present evidence to

the Court, which consists of the:

1. account ledger;

2. 5-day notice;

3. lease agreement; and

4. affidavit per Virginia Code Section 8.01-126.

A Court may require rent escrow before the tenant can request a continuance,

pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.25:1. Under Virginia Code Section 55-

248.25:1, where a landlord has filed an unlawful detainer action seeking possession of the

premises and the tenant seeks to obtain a continuance of the action or to set it for a

contested trial, the Court may, at that time, order the tenant to pay an amount equal to the

rent due as of the initial Court date into the Court escrow account prior to granting the

tenant’s request for a continuance. If the tenant asserts a “good faith defense,” and the

Court agrees, the Court shall not require the rent to be escrowed. Also, if the landlord

requests a continuance or to set the case for a contested trial, the Court shall not require

the rent to be escrowed. (See Virginia Code Section 55-248.25:1(A))

If the Court finds that the tenant has not asserted a “good faith defense,” the

tenant will be required to pay an amount determined by the Court to be deposited into the

Court escrow account for the case to be continued or to be set for a contested trial. In

addition, the Court may grant a tenant a continuance of no more than one week to make

the full payment to the Court of the ordered amount into the escrow account. If the tenant

fails to pay the entire amount ordered, the Court shall, upon the motion of the landlord,

enter judgment for the landlord for possession and for the amounts owed. The Court

shall further order that, should the tenant fail to pay future rent due under the rental

agreement into the Court escrow account, the Court shall, upon the motion of the

landlord, enter judgment for the landlord for possession and for the outstanding amounts

due and owing to the landlord. Upon motion of the landlord, the Court may disburse the

monies held in the Court escrow account to the landlord for payment of his mortgage or

other expenses relating to the dwelling unit.

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 8.01-129, as amended, in any unlawful detainer

action filed, if a judge grants the plaintiff a judgment for possession of the premises, upon

request of the plaintiff, the judge shall further order that the writ issue immediately upon

entry of judgment for possession. In such case, the clerk shall deliver the writ to the

sheriff, who shall then, at least 72 hours prior to execution of such writ, serve notice of

intent to execute the writ, including the date and time of the eviction. In no case,

however, shall the sheriff evict the defendant from the dwelling unit prior to the

expiration of the defendant’s 10-day appeal period. If the defendant perfects an appeal,

the sheriff shall return the writ to the clerk who issued it. Thus, the plaintiff or its counsel

should request immediate possession at the return date.

Page 10 of 24

Use of an Affidavit or Sworn Testimony for Default Judgment

In 2014, 2015 and 2017, the General Assembly amended Virginia Code Section

8.01-126 regarding what amounts the Court may award in the case of a default judgment.

As briefly noted in Step Four, the unlawful detainer form now includes a box for

“Plaintiff requests judgment for all amounts due as of the date of the hearing.” For a

landlord to recover all amounts sought as of the date of the hearing, that box must be

checked and the landlord, or landlord’s attorney, must provide to the Court at the hearing

date an affidavit or sworn testimony that describes the amount of outstanding rent, late

charges, attorney fees, and any other charges or damages due as of the date of the

hearing. Also, if the lease or rental agreement so provides, the amount of the rent due

shall include the entire month in which the hearing is held, and thus the rent shall not be

prorated.

Bifurcated Unlawful Detainer Actions

Virginia Code Section 8.01-128 was amended in 2005, 2016 and 2017 to give the

plaintiff the option of bifurcating the unlawful detainer trial on the issue of possession,

and on the issue of final rent and damages. Virginia Code Section 8.01-128 provides in

pertinent part as follows:

The plaintiff may, alternatively, receive a final, appealable judgment for

possession of the property unlawfully entered or unlawfully detained and

be issued a writ of possession, and continue the case for up to 120 days to

establish final rent and damages. If the plaintiff elects to proceed under

this section, the judge shall hear evidence as to the issue of possession on

the initial court date and shall hear evidence on the final rent and damages

at the hearing set on the continuance date, unless the plaintiff requests

otherwise or the judge rules otherwise. Nothing in this section shall

preclude a defendant who appears in court at the initial court date from

contesting an unlawful detainer action as otherwise provided by law.

If under this section an appeal is taken as to possession, the entire case

shall be considered appealed. The plaintiff shall, in the instance of a

continuance taken under this section, mail to the defendant at the

defendant's last known address at least 15 days prior to the continuance

date a notice advising of (i) the continuance date; (ii) the amounts of final

rent and damages; and (iii) that the plaintiff is seeking judgment for

additional sums. A copy of such notice shall be filed with the court.

Unauthorized Practice of Law

Property managers will often attempt to litigate unlawful detainer cases without the

assistance of an attorney. Property managers must be warned of the pitfalls of the

unauthorized practice of law statute. Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 54.1-3904, any

person who practices law without authorization or license shall be guilty of a Class 1

Page 11 of 24

misdemeanor. A pro se litigant may represent his own interests in a court of law;

however, a pro se litigant may not represent another entity or person. Thus, except in

limited circumstances, a property manager may only represent his interests and not those

of his apartment complex. Under Virginia Code Section 55-246.1, a property manager

may attend a return date and request appropriate relief from the Court as set forth in the

aforesaid code section. If the defendant/tenant appears at the return date and contests the

pending action, then the property manager may request a continuance. Note that the

property manager should obtain his attorneys’ available dates or the appointed Court date

may create scheduling problems for the attorney. Also, in a recent 2016 amendment to

Virginia Code Section 8.01-375, in an unlawful detainer action filed in general district

court, a managing agent, as defined under the VRLTA, is exempt from being excluded as

a witness upon a motion by the Court or by any one of the parties to the action.

STEP SEVEN – The Contested Hearing

As noted in Step Five, the landlord must prove the breach. Plaintiff’s attorney must

put on evidence of the lease, notice, and ledger. Also, the landlord must utilize testimony

from witnesses who observed the breach (for example, neighbors, police, or security

guards). The evidence must prove that the breach occurred, a notice was served on the

tenant/defendant, and the tenant/defendant failed to vacate the leased premises. Plaintiff

must also prove the amount of rent and fees owed to the plaintiff.

For a tenant, the landlord’s non-compliance may be used as a defense to an action for

possession for nonpayment of rent, pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.25.

Virginia Code Section 55-248.25 addresses the landlord’s non-compliance as a potential

defense for tenants involved in actions for possession for nonpayment of rent. In cases

where the landlord is pursuing an action for possession based on nonpayment of rent, the

tenant may assert as a defense that there exists upon the leased premises a condition or

conditions which “constitutes or will constitute, a fire hazard or a serious threat to the

life, health or safety” or is a material breach of the lease and/or a provision of law. Prior

to asserting this defense, however, there are certain requirements that the resident must

satisfy as set forth in subsections (A)(1) and (A)(2) of Virginia Code Section 55-248.25.

The landlord may respond by establishing that the conditions do not exist, or that they

have been removed or remedied, or that the conditions were caused by the resident, or

that the tenant has unreasonably refused entry to the landlord of the leased premises for

the purpose of correcting the condition.

As set forth in Virginia Code Section 55-248.25, a General District Court may make

findings of fact and enter an Order, including any one of the enumerated remedies that

are contained in subsections (C)(1) through (C)(3). If the Court finds that the tenant

raised this defense in bad faith or caused the violation or unreasonably refused entry to

the landlord for the purpose of correcting the condition, the Court, in its discretion, may

impose certain costs incurred by landlord, which could include court costs, costs of repair

if caused by tenant, and reasonable attorneys’ fees.

Page 12 of 24

STEP EIGHT – Post-Judgment Issues

Appeals

The plaintiff’s attorney must remember to post the bond on time if an appeal is to

be perfected. It is important for the practitioner to remember the commonly overlooked

point that unlawful detainer appeals require a bond to be posted, the writ tax and costs

paid, and the appeal to be noted, all within ten days from the date of judgment. Many

attorneys fail to pay the writ tax and costs and post the bond within the required ten day

period. It is important to remember that in unlawful detainer cases, the rule of thumb is

10/10 and not 10/30.

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 8.01-129, when the defendant appeals an

unlawful detainer, he must give security for all rent which has accrued and which may

accrue on the premises, but not for more than one year’s rent, and also for all damages

that have accrued or may accrue from the unlawful use and occupation of the premises

for a period not exceeding three months. The amount of the bond will be set by the Court.

Virginia Code Section 16.1-107 also provides that, in all civil cases, except trespass,

ejectment, unlawful detainer against a former owner based upon a foreclosure against that

owner, or any action involving recovering rents, no indigent person shall be required to

post an appeal bond.

Once a matter has been appealed from General District Court to Circuit Court,

execution on the order of possession is stayed. Therefore, it is often necessary to file

subsequent unlawful detainer actions for nonpayment of rent or other such breaches that

may occur during the months following the original case that has been appealed to Circuit

Court. These successive unlawful detainer actions demonstrate the defendant’s inability

or unwillingness to cooperate further with the landlord.

Bankruptcy

The eviction process may be disrupted when a tenant files a petition for

bankruptcy. Prior to April 2005, the automatic stay provisions of the Bankruptcy Code

prohibited the continuation of any eviction or unlawful detainer proceedings against a

tenant by a landlord of residential property, despite the landlord’s procuring a judgment

for possession of the leased premises prior to the commencement of the tenant’s

bankruptcy action. Under the old bankruptcy law, the automatic stay provision stalled

eviction proceedings.

The revised Bankruptcy Code allows a landlord to enforce pre-petition judgments

for possession without first obtaining an order from the Bankruptcy Court modifying the

automatic stay. Pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 362(b)(22), the automatic stay does not apply to

the continuation of eviction actions by a landlord involving residential leased property

whereby:

1. the debtor resides in the property as a tenant, and

Page 13 of 24

2. the landlord has obtained, before the bankruptcy, a judgment against the

debtor/tenant for possession of the property.

In these cases, the landlord does not need to file a motion to obtain relief from

automatic stay, and the landlord is free to continue pursuing its eviction rights and writ of

possession.

Limitations on the 11 U.S.C. § 362(b)(22) relief:

The provisions of 11 U.S.C. § 362(l) place conditions on the above referenced relief.

The conditions set forth a procedure whereby the tenant may attempt to retain

possession of the property.

Under 11 U.S.C. § 362(l), the debtor is allowed to file and to serve, by no later than

30 days after the bankruptcy petition is filed, a certification under penalty of perjury.

The automatic stay will apply for the first 30 days of the bankruptcy case if the debtor

attests to the following:

o Under applicable non-bankruptcy law (i.e. Virginia law, etc.), circumstances

exist that permit the debtor to cure the entire monetary default giving rise to

the judgment for possession (for example, the debtor has a right of redemption

available pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.34:1);

o The debtor has deposited with the Bankruptcy Court Clerk any rent that would

become due during the 30-day period after the petition is filed; and

o Within 30 days after the case is filed, the debtor cures all monetary defaults

giving rise to the unlawful detainer action.

The landlord may object to the debtor’s certification. If the landlord contests the debtor

certification, the Court must hold a hearing within 10-days to determine the truth of the

challenged certifications. If the Court upholds the landlord’s objection, the automatic

stay is terminated, and the landlord will be entitled to proceed under Virginia law to

complete the eviction process and to recover possession of the property. (See 11 U.S.C.

§ 362(l)(3)(B)).

Eviction processes initiated due to endangerment of property or illegal use of

controlled substances on the leased premises are less susceptible to an automatic stay

under bankruptcy law. Pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 362(b)(23), the automatic stay will

terminate 15 days after the landlord files a certification, if the landlord certifies under

penalty of perjury that:

1. The landlord’s unlawful detainer is based on the endangerment of the

leased premises, or the illegal use of controlled substances on the leased

premises; or

2. The tenant, during the 30-day period preceding the filing of the

certification, has endangered the leased premises or illegally used a controlled

substance on the leased premises.

Page 14 of 24

The tenant may file and serve an objection to the landlord’s certification within 15

days after the certification is filed challenging the truth of the landlord’s certification.

(See 11 U.S.C. § 362(m)). Then the automatic stay will prohibit further eviction actions

until the Bankruptcy Court conducts a hearing on the objection within 10-days. At the

hearing, the Court is required to determine whether “the situation giving rise to the

lessor’s certification . . . existed or has been remedied.” (See 11 U.S.C. § 362(m)(2)(B)).

If the tenant demonstrates to the Court that the situation giving rise to the landlord’s

unlawful detainer action did not exist, or has been remedied, then the stay will remain in

effect. (See 11 U.S.C. § 362(m)(2)(C)). If the tenant does not prevail at this hearing, the

landlord will be entitled to take further action to recover possession of the leased

premises under Virginia law. (See 11 U.S.C. Section 362(m)(2)(D)).

STEP NINE - Obtain and Execute a Writ of Possession

Following the entry of judgment and the expiration of the 10 day period within

which a defendant may appeal a judgment in plaintiff’s favor, the plaintiff is permitted to

file for and to obtain a writ of possession pursuant to Virginia Code Sections 8.01-471

and 8.01-293. A writ of possession may be issued up to one year following the date of

judgment for possession, and the writ of possession must be returnable within 30 days

from the date of issuing the writ. Note: Courts should only award “immediate”

possession in the event of default judgments, for cases of nonpayment of rent, and for

immediate non-remediable breaches of the lease.

The landlord or property manager will not be permitted to issue a writ if he has

accepted rent payments without reservation. (See Virginia Code Sections 8.01-471 and

55-248.34:1). The request for a writ of possession must be filed with the clerk’s office

and the clerk must be provided with three copies of the writ of possession. As stated in

Virginia Code Section 8.01-293, only the sheriff may execute the writ. The sheriff will

travel to the leased premises and physically remove the tenant from the premises. This

step actually results in the removal of the tenant and effectively closes the eviction

process. Note: The sheriff will maintain the peace, but he or she will not remove the

tenant’s personal property or anything else that needs to be removed from the premises.

If you anticipate having to remove any personal property belongings located in the unit,

you then should be prepared to have those belonging removed pursuant to Virginia Code

Section 55-248.38:2 as described below.

Personal Property Issues

As briefly noted in Step One, following the termination of the lease (not following

the execution of a writ of possession), Virginia Code Section 55-248.38:1 describes how

a landlord can handle the disposal of personal property items that were abandoned by the

tenant in the premises or in any storage area provided by the landlord. The landlord must

give the tenant notice by:

Page 15 of 24

1) Providing a termination notice that includes a statement that any

personal property left in the premises will be disposed of within the 24-

hour period after termination of the lease;

2) Providing written notice pursuant to Section 55-248.33 that includes a

statement that all personal property left in the premises will be disposed

of within the 24-hour period after the seven-day notice period expires;

or

3) Providing separate written notice to tenant that all personal property left

in the premises will be disposed of within 24 hours of the ten (10) day

notice period expires.

It is important to note that the landlord must allow the tenant reasonable access to the

property until the time in which the property is disposed. What that means in practice is

that, once any statutory notice period has expired, the landlord should promptly dispose

of the personal property. If the landlord waits and denies the tenant’s request for

reasonable access to the personal property even after the required wait period has expired,

then the tenant is entitled to injunctive relief and other relief provided by law (typically

damages for the value of the personal property being detained.)

Virginia Code Section 55-248-38:2 provides how a landlord may treat personal

property remaining in the premises following a judgment for possession in an unlawful

detainer action. The statute provides the landlord with two options:

1) execute the writ of possession and remove the personal property to the nearest

public way for 24 hours after which the landlord must dispose of the property; or

2) execute the writ of possession and store the personal property in a storage area

designated by the landlord (which can be the leased premises itself) for 24 hours

and then dispose of it.

If the landlord chooses the storage area option, the tenant must be provided access, at

reasonable times, to the personal property until the landlord disposes of it. If such

reasonable access is denied, the tenant is entitled to injunctive relief and any other relief

provided by law.

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.38:3, upon the death of a tenant, who is

the sole occupant of the dwelling unit, the lease is considered terminated and the landlord

does not need to file an unlawful detainer action to obtain possession. The estate is liable

for actual damages described in Virginia Code Section 55-248.35. It is important to

immediately secure the leased premises. Pictures or an inventory may be useful should

there be any allegations of missing or stolen property in the future. Once the leased

premises have been secured and protected, then landlord should check with the Court to

see if an executor or an administrator has been appointed to handle the probate. If no one

has been appointed, the landlord must give at least 10 days’ written notice to the

emergency contact person identified in the lease or in any other related document, or if no

such person is identified, then to the deceased tenant pursuant to Virginia Code Section

55-248.6. The notice must include a statement that all personal property items will be

Page 16 of 24

treated as abandoned in accordance with Virginia Code Section 55-248.38:1 unless

claimed within 10 days. After the notice requirement has been satisfied, the landlord can

treat the remaining personal property as if it were abandoned and dispose of it according

to Virginia Code 55-248.38:1.

STEP TEN - Acceptance of Rent During the Eviction Process

Although this step is not always utilized, it is critical for landlords to understand

the rules regarding the acceptance of rent during the eviction process. Rules governing

the acceptance of rent during the eviction process are found in Virginia Code Sections

55-225.47 & 55-248.34:1. If a landlord chooses to accept the tenant’s rent following the

issuance of a notice to the tenant that the lease is in breach and that the landlord intends

to pursue legal action, the landlord must also give written notice to the tenant that the rent

is and will be accepted with reservation. The notice may be included in the termination

notice given by the landlord to the tenant, or in a separate written notice given by the

landlord to the tenant. If so done, no further or subsequent notice of the landlord’s

acceptance of rent with reservation need be given by the landlord to the tenant, which

includes the following of the Court’s entry of judgment for possession but prior to the

eviction. Thus, the notice need only be given once in order to secure the landlord’s right

to continue receiving and to accepting rent as well as to continue pursuing possession of

the leased premises. (See 2018 amendments to Virginia Code Sections 55-225.47 & 55-

248.34:1)

In Virginia, tenants are permitted to invoke a one right of redemption during a 12-

month period. If the tenant pays all amounts owing, including rent, late fees, attorney’s

fees, and court costs, at or before the first return date of the unlawful detainer action, then

the tenant must be permitted to remain in the leased premises. The tenant, however, may

only invoke this right of redemption once within a 12-month period. If the tenant timely

invokes the one right of redemption, then the landlord must dismiss the pending unlawful

detainer action at that time. The landlord should retain proof of the tenant’s exercise of

the one right of redemption. This will afford the landlord proof that the tenant has

already exercised his or her one right of redemption should the tenant fail to timely pay

the rent required under the lease agreement within the next 12-month period.

Questions:

1) Can a landlord accept partial rent and still have the tenant evicted from the

unit?

Pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.34:1, the landlord may accept rent or

partial rent with reservation and still seek possession of the leased premises. To

avoid a waiver by accepting rent or partial rent, the landlord must strictly comply

with the requirements set forth under Virginia Code Sections 55-225.47 and 55-

248.34:1.

Page 17 of 24

DAMAGES

The VRLTA allows the landlord to claim the following damages if the lease

agreement is terminated:

1. Possession;

2. Rent;

3. Late Fees;

4. Costs

5. Reasonable attorneys’ fees;

6. Actual damages of the breach.

Possession

How to obtain possession is discussed in detail in the preceding sections of this

outline.

Rent

Most people think of rent as simply the required monthly payment the tenant

makes as specified under the lease. However, the VRLTA defines rent as “all money,

other than a security deposit, owed or paid to the landlord under the rental agreement,

including prepaid rent paid more than one month in advance of the rent due date,” which

broadens rent to include other fees and damages incurred under the lease. (See Virginia

Code Sections 55-248.4 and 55-248.32.)

While rent may seem a straightforward category of damages, there are some

issues to keep in mind. First of all, as briefly noted in the Eviction guide, the July 2014

unlawful detainer form includes a box that indicates that the plaintiff will seek rent owed

as of the date of the hearing. It is important to check that box so that you can easily

amend the amount of rent you are seeking (in lieu of more complicated motions for leave

to amend). However, there will always be additional rent after the first contested hearing,

so how can you recover that additional rent? There are two options a plaintiff can pursue.

Before 2005, after a plaintiff has successfully completed the unlawful detainer

action, he or she would have to file a warrant in debt for any rent and damages not

recovered under unlawful detainer action. Currently, the main appeal to this method is

that the landlord has time to fully assess all of his damages and document his claim

accordingly. Additionally, certain landlords as a business model have an organizational

separation between unlawful detainers and collecting outstanding debts, for example

retaining collection agencies for the latter. The downside to that approach is that it

involves separate litigation with additional costs and extra efforts (such as finding and

serving the tenant for whom you may not have any contact information).

As briefly noted Step Six, since 2005, Virginia Code Section 8.01-128 has

allowed a plaintiff to bifurcate the unlawful detainer action as to possession and damages.

Page 18 of 24

This allows a landlord to capture more damages in a single unlawful detainer action. The

hearing on damages must be held within 120 days of the hearing on possession.

However, the 120-day period should capture the significant majority, if not all, of a

landlord’s damages. Before the damages hearing, the landlord will have possession of

the premises and will be able to fully assess any damage above normal wear and tear.

Furthermore, if the landlord is able to re-rent the leased premises during that time period

then that turnover period, in which no rent was received, can be claimed as outstanding

rent. If the premises are still not re-rented, then at least the landlord can claim the entire

120-day window. Keep in mind, however, that the landlord must make a good-faith

effort to mitigate the damages, which would include standard business efforts to re-rent

the premises.

Late Fees

Virginia Code Section 55-248.7 specifically authorizes a landlord to charge a fee

for a tenant’s late payments, although it does not specify an amount. Courts will

normally view late fees as a matter of contract law and will strictly construe the statutory

language, allowing for reasonable “late charges contracted for in a written rental

agreement.” However, Courts will weigh the reasonableness of assessed late fees.

Generally, Courts will approve a late fee of up to 10% of the monthly rent.

Costs

While “costs” may sound like a broad category of damages, it only applies to the

cost of filing and service of process by the local sheriff. Typically, the cost of filing an

unlawful detainer action ranges from $50-$70; whereas the cost for service of process by

a sheriff is currently $12. Therefore, the “costs” area of recovery is quite limited.

Reasonable Attorneys’ Fees

Similar to late fees, the VRLTA includes various sections that allow the landlord

recovery of attorneys’ fees with no other guidance except that they must be “reasonable.”

In smaller, more “run of the mill” unlawful detainer actions, Courts will generally

approve attorneys’ fees as a reasonable percentage (usually 25%-33%) of the judgment

awarded. However, in larger, more complex litigation, Courts may require proof of

actual attorney fees incurred. Note: A landlord cannot include or add charges for

attorneys’ fees without actually retaining and having an attorney present at the hearing.

Actual Damages

Rent and late fees are the most straightforward actual damages in that the amounts

are specified in the lease agreement. However, the Landlord can recover for other

damages actually incurred. Most commonly, such damages will be repairs to the

premises for damages incurred above normal wear and tear. As noted in Step Five, if a

particular item in the leased premises is damaged and requires repair, then the landlord

can recover the actual cost of repair. If the item must be replaced, however, then the

Page 19 of 24

landlord can only charge the actual value of the item being replaced, accounting for

depreciation. Unpaid utilities are also a common component of actual damages that a

landlord may need to recover. Regardless of the nature of the damages, the landlord

should be prepared to provide receipts and testimony to the Court, detailing the damages

and explaining with specificity how it was incurred. Note: The VRLTA does not

provide for punitive damages.

Remedy by Repair

It is helpful to note that pursuant to Virginia Code Section 55-248.32, if the tenant

violates a provision of Virginia Code Section 55-248.16 (detailing tenant’s duties to

maintain premises) or a provision of the lease agreement materially affecting health and

safety that can be remedied by repair, replacement, or cleaning, the landlord shall send a

written notice to the tenant specifying the breach and stating that the landlord will enter

the dwelling unit and will perform the work in a workmanlike manner and will submit an

itemized bill to the tenant for the actual and reasonable cost of the repair, which shall be

due as rent on the next rent due date, or if the rental agreement has terminated, for

immediate payment. This section specifically authorizes the landlord to “engage a third

party” to perform such repairs. In the event of an emergency, the landlord may enter the

premises and repair the damage following the same procedures.

CHALLENGES TO TITLE IN UNLAWFUL DETAINER ACTIONS

Another recent issue that has been raised by the Virginia Supreme Court is the

ability of General District Courts to consider challenges to a plaintiff’s title to property in

an unlawful detainer action. In Parrish v. Fannie Mae, the Supreme Court held that,

while a General District Court lacks subject matter jurisdiction to hear title challenges to

real property, the court may nonetheless consider whether such a challenge is legally

sufficient to justify a dismissal without prejudice on jurisdictional grounds. See Parrish

v. Fannie Mae, 292 Va. 44, 787 S.E.2d 116 (2016)(a copy of which is attached hereto).

This holding now raises the question as to what evidence a General District Court may

consider in making such a determination.

Overview of the Parrish case

In Parrish, the plaintiff, Fannie Mae, received a deed of trust to the defendants’

real property, and it thereafter sought to take possession of the defendants’ property

pursuant to an unlawful detainer action in general district court. Id. at 48, 787 S.E.2d at

119. The defendants responded to the unlawful detainer action by arguing that the

underlying foreclosure action was invalid due to plaintiff’s failure to comply with a

condition precedent inherent in the deed of trust. See id. The General District Court

nonetheless awarded possession to Fannie Mae, and the defendants filed an appeal to the

Circuit Court. Id.

In the Circuit Court, Fannie Mae argued that the Court should not consider any

defenses relating to the validity of the underlying foreclosure action due to the fact that

Page 20 of 24

the General District Court lacked subject matter jurisdiction to hear a title challenge in an

unlawful detainer action. Id. In essence, Fannie Mae’s argument was premised on the

Circuit Court’s jurisdiction being “derivative of the general district court’s subject matter

jurisdiction…” Id. at 48, 787 S.E.2d at 119-20. The Circuit Court agreed with Fannie

Mae, and it granted Fannie Mae an order of possession. Subsequently, the Virginia

Supreme Court awarded the defendants an appeal. See id. at 48, 787 S.E.2d at 120.

In assessing this case, the Virginia Supreme Court noted that “[g]eneral district

courts have subject matter jurisdiction over unlawful detainer cases. What they lack is

subject matter jurisdiction to try title.” Id. at 53, 787 S.E.2d at 122, n.6. “[C]ourts not of

record have no subject matter jurisdiction to try title to real property.” Id. at 49, 787

S.E.2d at 120. This, however, placed the Court in what it characterized as a

“conundrum” due to the fact that unlawful detainer actions can hinge on the outcome of a

title question. Id. at 50, 787 S.E.2d at 120-21.

“Because a court always has jurisdiction to determine whether it has subject

matter jurisdiction, the court has the authority to explore the allegations to determine

whether, if proven, they are sufficient to state a bona fide claim that the foreclosure sale

and trustee’s deed could be set aside in equity.” Id. at 52, 787 S.E.2d at 122 (internal

citation and quotation omitted). Thus, the Court held that “[i]f the general district court

satisfies itself that the allegations are insufficient, it retains subject matter jurisdiction and

may adjudicate the case on the merits. However, if the court determines that the

allegations are sufficient, it lacks subject matter jurisdiction over the case and it must be

dismissed without prejudice.” Id. at 53, 787 S.E.2d at 122.

Ultimately, the Court found that the defendants raised a bona fide question of title

in the unlawful detainer proceeding, thereby divesting the General District Court of

subject matter jurisdiction to try the unlawful detainer case before it. Likewise, since the

Circuit Court’s jurisdiction on appeal was derived from and limited to the jurisdiction of

the General District Court, the Circuit Court likewise lacked subject matter jurisdiction

while exercising its de novo appeal. Thus, the Circuit Court was limited to dismissing

the proceeding without prejudice. Therefore, the foreclosure purchaser was enabled to

pursue its choice of available remedies in the Circuit Court under that Court’s original

jurisdiction. Id. at 54, 787 S.E.2d at 123.

Application of Parrish to General District Court Proceedings

Though Parrish makes it clear to courts not of record that they are not required to

dismiss unlawful detainer actions immediately upon a defendant’s challenge to a

plaintiff’s title, the case nonetheless leaves an open question as to precisely how the

General District Courts should handle such a challenge.

What procedures should a General District Court follow when evaluating a title challenge

pursuant to Parrish?

Page 21 of 24

While Parrish does not identify the exact procedures a General District Court

should follow in hearing a title challenge in an unlawful detainer action, there is language

in this decision that should give courts some guidance. Ultimately, General District

Courts should consider only such evidence as is necessary to decide whether the

defendant’s response to the plaintiff’s claim introduces a legally sufficient title challenge.

This approach is evidenced by the Supreme Court’s underlying characterization of

a defendant’s title challenge. In essence, the Supreme Court suggests that a General

District Court only has jurisdiction to consider such a challenge insofar as it is necessary

to determine whether the court has subject matter jurisdiction. See Parrish, 292 Va. at

52, 787 S.E.2d at 122 (indicating that “a court always has jurisdiction to determine

whether it has subject matter jurisdiction…”) (quoting Morrison v. Bestler, 239 Va. 166,

170, 387 S.E.2d 753, 755 (1990)). The implication here is that a General District Court is

in no way meant to consider the merits of the title challenge, but rather they are only to

consider the legal sufficiency of the challenge itself.

Indeed, the Virginia Supreme Court states that “the allegations must be sufficient

to survive a demurrer had the homeowner filed a complaint in circuit court seeking such

relief.” Id.; cf. Filak v. George, 267 Va. 612, 617, 594 S.E.2d 610, 613 (2004) (“a

demurrer admits the truth of all facts alleged in a [complaint] but does not admit the

correctness of the pleader’s conclusions of law”). This language suggests that General

District Courts should generally evaluate a title challenge in an unlawful detainer action

in the same manner as they would in evaluating a demurrer to a complaint. In other

words, the General District Court should treat the case as if the moving party was

demurring to the allegations set forth in a pleading, and in so doing the court should only

consider the four corners of the parties’ respective pleadings.

This concept is somewhat confusing given that a party’s claim or challenge made

in a General District Court proceeding is not always set forth in a formal amplified

pleading filed with the Court. Accordingly, it may be wise for a General District Court to

order pleadings to be filed in a scenario where a defendant challenges the plaintiff’s title

to the disputed property.

What factors should a General District Court consider when evaluating a title challenge

pursuant to Parrish

Another issue raised by the Parrish decision is a determination of what factors the

court is to consider in evaluating whether the defendant’s argument is sufficient to state a

claim. Fortunately, the Parrish court provides a relatively clear answer to this question in

a footnote, when it states:

The Homeowner’s allegations must (1) identify with specificity the

precise requirements in the deed of trust that he or she asserts constitute

conditions precedent to the foreclosure, (2) allege facts indicating that the

trustee failed to substantially comply with them so that the power to

Page 22 of 24

foreclose did not accrue and (3) allege that the foreclosure purchaser knew

or should have known of the defect.

Id. at 53, 878 S.E.2d at 122, n. 5.

Thus, a court should look to a defendant’s argument with respect to whether it

introduces each of these elements, understanding and recognizing that a “general

allegation that the trustee breached the deed of trust is not sufficient.” Id. Where it does

not, the court should find that the defense was not properly raised, and accordingly, the

court should recognize its subject matter jurisdiction and move forward in deciding the

plaintiff’s unlawful detainer case. Alternatively, if these allegations are raised and are

sufficiently set forth, the court should find that it lacks subject matter jurisdiction and

dismiss the case without prejudice.

Are there situations where a General District Court can hear evidence in a title challenge?

One final consideration is whether there are circumstances in which the General

District Court may look beyond the four corners of the pleadings. Given that the Parrish

Court did not expressly say that a General District Court may only treat such a title

challenge like a demurrer, the Virginia Supreme Court has arguably left some room for a

General District Court to consider and to entertain evidence beyond the pleadings when a

title challenge is raised.

Ultimately, any evidence heard by a General District Court in the context of a title

challenge during an unlawful detainer action should be heard exclusively for the sole

purpose of determining whether the title challenge is legally sufficient. Just as a trial

court is not to evaluate the merits of a plaintiff’s complaint when ruling on a demurrer but

rather only to evaluate the legal sufficiency of it, General District Courts should likewise

be cautious so as not to evaluate the merits of a title challenge in an unlawful detainer

action.

In most cases, a court will likely be able to determine whether a title challenge is

adequate by merely listening to the defendant’s argument and/or reviewing the

defendant’s pleadings. Nonetheless, situations could arise where evidence needs to be

heard in order to make such a determination. The most obvious example is where an

unrepresented defendant suggests that there is a title problem, but the defendant has

limited knowledge of the law with respect to title issues. In such a case, the Court may

ask to see certain mortgage or title documents solely for the purpose of understanding the

defendant’s argument. Moreover, the court in such a situation may also wish to advise the

defendant of the complex nature of this argument and to encourage the defendant to

obtain counsel.

Page 23 of 24

Summary of Title Challenge Procedures and Considerations

Based on the above discussion, where a defendant in an unlawful detainer action

alleges that the plaintiff lacks adequate title to the disputed property, a Court should

consider the following:

STEP 1—Is the defendant’s argument clear?

If the defendant understands the argument in full and presents it to the court in a

coherent fashion, the court may be able to make an immediate decision as to

whether the argument is legally sufficient.

If the defendant’s argument is ambiguous, the court may wish to order pleadings

to obtain a clear and amplified statement of the defendant’s position.

If the defendant is unrepresented and does not seem to fully understand the

implications of the argument, the court should consider advising the defendant to

obtain counsel. The court may further ask for certain documentation so as to help

with understanding the nature of the defendant’s arguments. However, the court

should not consider evidence to evaluate the merits of the defendant’s challenges.

STEP 2—Is the defendant’s argument legally sufficient?

The underlying question is whether the title challenge has been sufficiently raised

such that the court can determine whether or not it has subject matter jurisdiction.

The court should NOT evaluate the merits of the defendant’s challenge.

The court should consider whether the defendant’s challenge satisfies the

following elements:

1. Does the defendant’s claim identify with specificity the precise

requirements in the deed of trust or other mortgage document that he or

she asserts constitutes conditions precedent to the foreclosure?

2. Does the defendant allege sufficient facts indicating that the trustee failed

to substantially comply with these conditions such that the power to

foreclose did not accrue?

3. Does the defendant allege that the foreclosure purchaser knew or should

have known of the defect?

STEP 3—Does the defendant’s argument justify dismissal?

If the court determines that the defendant’s argument does not raise a legally

sufficient title challenge, the court should then find that it has subject matter

jurisdiction and proceed forward in deciding the merits of the unlawful detainer

action.

9

9

It is important to note again that the court should never consider the merits of the title dispute. If the court

has determined that the defendant has not introduced a legally sufficient claim, the court should then

disregard this argument entirely in the context of the plaintiff’s claim. This is because the court lacks

Page 24 of 24

If the court determines that the defendant’s argument does raise a legally

sufficient title challenge, the court should then dismiss the case without prejudice

on the basis that the court lacks subject matter jurisdiction.

Examples

1. If the defendant alleges the trustee failed to properly advertise the sale, may the

court receive evidence of the newspaper’s certificate of publication?

A district court should generally not receive evidence of the newspaper’s

certificate of publication. This evidence would likely be pertinent only to deciding the

merits of the defendant’s argument.

Instead, the court should consider 1) whether the defendant has identified the

precise requirements that the trustee was to abide by with respect to publication; 2)

whether the defendant alleged sufficient facts suggesting that the trustee substantially

failed to comply with these publication requirements; and 3) whether the foreclosure

purchaser knew or should have known of the trustee’s failure to comply with the

advertising requirements.

2. If the defendant alleges that a trustee’s report of the foreclosure was not filed

with and approved by the Commissioner of Accounts, may the Court receive

evidence of the Commissioner’s approval of the report?

A General District Court should generally not receive evidence of a

Commissioner’s Approval of a Report of Foreclosure as this also may be relevant only to

determining the merits the defendant’s title challenge. Instead, the court should again

only focus on the above three (3) stated criteria and what facts, if any, have been alleged

that would satisfy them.

3. If the defendant alleges lack of notice of the sale, may the court receive evidence

of a certified return receipt of mailing of the notice of sale to the defendant?

As with the other above examples, this evidence would also be relevant only to

determining the merits of the defendant’s title claim. Though this evidence would

arguably be dispositive in disproving the defendant’s argument, the district court’s role is

limited only to a determination of whether the claim is properly raised and not whether

the claim has merit. If a claim is sufficiently raised, the court lacks subject matter

jurisdiction to evaluate the merits and must dismiss the case without prejudice.

subject matter jurisdiction to hear the title claim and may only proceed on the merits of the plaintiff’s claim

in the event that the defendant’s title challenge is determined to be legally insufficient.